|

With tragedy in Japan dominating the news last week, the Federal Reserve’s policy meeting garnered much less of Wall Street’s attention than it usually does. Perhaps investors should have spent a little more time with Tuesday’s post-meeting statement from the Fed’s policy committee. A notable shift in the Fed’s thinking on both growth and inflation may complicate matters for policymakers later this year, especially as events in Japan and oil-producing nations in the Middle East and North Africa play out.

The Fed’s Federal Open Market Committee cast aside much of the caution on the strength and durability of the economic recovery that was prominent in past statements, while drawing more attention to upward pressure on inflation from energy and other commodities. “The shift in tone was larger than we had expected,” says Barclays Capital economist Michael Gapen.

The statement was far from hawkish, but for the first time since the financial crisis, the Fed appears to be much less concerned about the risk of deflation and more worried about the risk of leaving interest rates too low for too long. The policy committee appears to be incorporating the inflation concerns of some of its more vocal members, who have been openly skeptical of the Fed’s $600 billion asset purchase program, or QE2, intended to keep interest rates low. The change in tone strongly suggests that, once the program of buying Treasury securities is finished in June, any new round of purchases is highly unlikely if the economy continues to perform as it has.

Policymakers omitted several references to concerns about economic growth that had been standard in past statements. They abandoned remarks about the reluctance of companies to increase payrolls, factors holding back consumer spending, and “disappointingly slow” progress in achieving their dual goals for growth and inflation. Instead, they said the job markets were “improving gradually” and the recovery was on “firmer footing.”

The Fed explicitly said higher prices for energy and other commodities “are putting upward pressure on inflation” and that it would “pay close attention to the evolution of inflation and inflation expectations.” Although the committee predicted the energy effect will be “transitory” and said underlying inflation outside of energy and food is “subdued,” it is no longer saying the underlying trend is downward. Economists at UBS say the statement was especially notable in that policymakers now seem to view higher energy prices in terms of their potential to lift inflation rather than cut into growth.

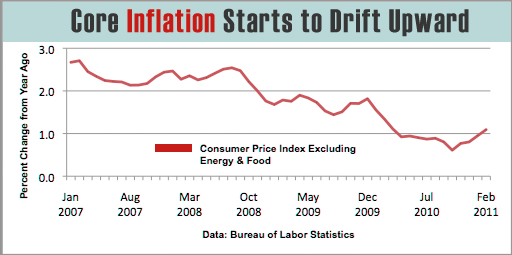

The latest price reports drew attention to just that point. Inflation measured by the consumer price index over 12 months stood at 2.1 percent in February, nearly double the 1.1 percent rate in October. More important, core inflation, which looks at prices excluding energy and food, also nearly doubled, to 1.1 percent in February from 0.6 percent in October. Further pressure is building in the pipeline, as wholesale prices for consumer goods other than energy and food continued to grow at a faster rate in February, rising 2.6 percent from a year ago. Plus, inflation for imported goods other than fuels continues its steady climb, rising to 3.6 percent in February, the highest in more than two years. Barclays economists say the reports offer evidence that prices across a broad range of goods and services are gradually starting to respond to the pickup in economic activity.

Over the past three months, consumer prices excluding energy and food have risen 1.8 percent, measured at an annual rate, suggesting further acceleration in the 12-month pace of core inflation this spring. That’s still below the Fed’s 2 percent or so comfort level, but UBS analysts note that any acceleration beyond that would make it difficult for the Fed to say inflation is “subdued.” Core inflation tends to fall for a year or two into a recovery in a lagged response to weakness in demand. With the recovery two years old this June, core inflation is starting to pick up.

Policymakers are especially concerned about inflation expectations, which can become embedded in price-setting and buying behavior, pushing inflation higher. Some measures of expectations have drifted up since last summer but remain within their typical range. Short-term gauges, such as the Reuters/University of Michigan survey of consumer sentiment, recently have jumped sharply higher, tracking the surge in energy and food costs.

The Fed’s own survey, prepared for last week’s policy meeting, noted that some manufacturers were “passing through higher input costs to customers” and some retailers “had implemented price increases,” while other manufacturers and retailers said they were planning to raise prices. In the past, companies had told the Fed they could not raise prices for fear of losing customers.

One potential complication from the devastation in Japan is shortages of parts and products. “There will also be production bottlenecks in the U.S. to contend with,” says Stuart Hoffman, chief economist at PNC Bank in Pittsburgh. Shortages and bottlenecks give producers more pricing power, especially in a growing economy with improving labor markets.

At the same time, the situation in the Middle East and North Africa is hardly stable, given the possibility of military action in Libya and Saudi Arabia’s military efforts to crush protests in Bahrain, which could fuel unrest at home for the world’s largest oil producer. Plus, the potential for violence surrounding upcoming elections in Nigeria, which produces about 40 percent more oil than Libya, could add to market volatility.

All in all, policymakers at the Fed, as well as investors, are betting that the spike in prices for oil and other commodities is temporary and the amount of slack in the economy associated with the 8.9 percent jobless rate will keep inflation under wraps. However, the latest price indexes show that inflation has clearly bottomed out for this business cycle and core inflation is gradually starting to rise. If price pressures continue to build, the financial markets may have to adjust to the possibility that the Fed will start raising rates sooner rather than later.

Related Links:

Inflation Slowly Showing Signs of Life (Wall Street Journal)

Inflation: A Look Inside the CPI (Seeking Alpha)

Fed’s Next Steps as Asset Purchases Wind Down Divide Economists (Bloomberg)