Fifty years ago, post-World War II prosperity created a new stage of life for the Baby Boomers’ parents. It was retirement, a golden period marked by cruises, RV odysseys, and rampant spoiling of grandchildren. But the Great Recession and the Looming Entitlement Crisis are now creating a new life stage for the boomers and their successors. Financial planners and social analysts call it “phased retirement,” “transition,” or just “working longer.” Fiscal policy makers call it “a tax windfall” and “the easiest way to shore up Social Security’s finances and postpone Medicare’s collapse.” Baby Boomers simply might say, “I can never afford to retire.”

But maybe it won’t be so bad. Alicia Munnell, Director of Boston College’s Center for Retirement Research and author of Working Longer: The Solution to the Retirement Income Challenge, is often at pains to explain that working just three or four years longer puts many workers back in a stronger position. (On the fiscal side, raising the normal retirement age by one year immediately would cut 35% of Social Security’s funding shortfall all by itself, and keeping people in the workforce just two years longer would significantly decrease the drag that the boomers’ retirement will have on GDP and tax revenues. On the personal side, Christine Fahlund, the financial planning director at mutual fund company T. Rowe Price, recently circulated an illustration suggesting that transition (as she calls it) can be as much fun as retirement and still leave you in better shape to face life after the paycheck.

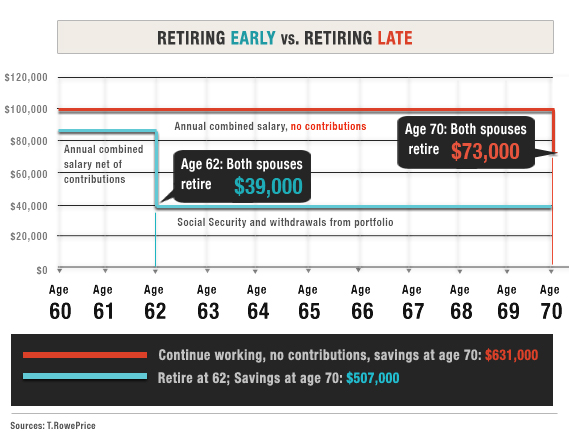

Fahlund takes the example of two couples at age 60. One couple saves like crazy (15% of income) and retires at 62, the earliest age of Social Security eligibility. The other saves nothing and instead spends 15% of their income on cruises, RVs and other indulgences until retiring at 70. Who ends up richer for the rest of their life? Why, the spendthrift couple with the phased retirement, of course.

Why does it work that way?

- Retiring at 70 rather than 62 means you have to support yourself without a paycheck for eight fewer years. So, for the same size nest egg, you can take more income if you start drawing it down eight years later.

- Your Social Security benefit grows every year you delay claiming. For a top earner, the maximum Social Security benefit grows from $21,600 a year for someone retiring at 62 to $38,300 at 70.

- You have eight more years to save and your savings have eight more years to grow.

The problem, as grumbling boomers are quick to point out, is who wants to keep slaving away until age 70? Fahlund’s answer: It all depends on how you define “slaving.”

The key to making the retirement transition work, in Fahlund’s vision, is to start enjoying a classic Greatest Generation “retirement” before you actually leave work. Collecting a pay check for a few extra years gives you more income to spend on cruises and grandchildren. In Fahlund's example, the delayed retirees come out ahead even if they don't save a penny during their "transition" phase because they don't need to draw on their savings. Meanwhile, the nest egg they already had continues to compound, in Fahlund's example, by 7% a year.

The numbers make Fahlund's case for phased retirement: Both couples hit age 60 with the same $450,000 in the bank, and, yes, the hard-saving early retirees hit age 62 with a bigger sum. But because they would have to draw on that savings starting at 62 to support their retirement, they would have just over $500,000 by age 70. The delayed retirees, by contrast, hit 70 with nearly $130,000 more, despite their free-spending 60s, because they would be able to let their money grow untouched for an extra eight years.

Will boomers come to cherish their prolonged retirement transition, the way their parents came to enjoy retirement? As Munnell points out, a lot has to happen first. For starters, employers need an attitude adjustment. “Employers are ambivalent about older people, at best,” she says. Some 40% of retirees never make it to their intended retirement age because of illness or layoff—and, remember, that intended retirement age is usually 65, not 70.

Just as important, the financial markets have to cooperate. What if, instead of getting the 7% that T. Rowe Price predicts, you get 2.6%, the current rate of return on 7-year Treasury bonds? The payoff for staying on the job becomes much less generous. A flat or even shrinking 401(k) during the transition years—remember 2000 to 2008—will make those cruises seem like less of an advance on traditional retirement and more like a dangerous indulgence. A boomer would have to be very confident in the future to spend like Fahlund suggests.

For a whole lot of reasons, it’s clear that phased retirement is going to be the model for a growing number of boomers at the twilight of their careers. Boomers should plan on working later and policy makers should encourage them (and especially their employers) to make it possible. It’s less clear that phase of life will be another set of golden years, as it appears in Fahlund’s illustration. It may, in fact, just seem a lot like just more work.