It will start sometime around the middle of next week. Financial journalists and social media-savvy economists will write “table setters” about the monthly jobs release from the Bureau of Labor Statistics, which is due out next Friday morning.

By next Thursday night, things will heat up on Twitter, as the same crowd begins offering their over-under predictions for the number of jobs the U.S. economy created in August.

Related: Sluggish Wages Hurt the Unemployed

By Friday morning, things will have reach a contrived sort of fever pitch as reporters, half-jokingly, post countdowns to the release and confess their (completely fabricated, I hope) physical reactions to the suspense. “Eyes twitching” is a favorite. “Palms sweating” is another.

But here’s the thing: The U.S. economy has created more than 200,000 jobs per month for six months. The trend is clear. The economy is on the mend, and the unemployment rate is coming back down. Even people who had left the workforce in despair are pouring back into the ranks of the jobseekers because they have renewed hope of finding employment.

The question is no longer how many jobs the U.S. economy created in a given month. We can be reasonably sure that the number will be positive and it will number in the low hundreds of thousands. The real questions are what kind of jobs it is creating, and are they the kind we really want?

The BLS, which conducts a weeklong “reference” survey every month to determine jobs growth, counts a person as employed “if they did any work at all for pay or profit during the survey reference week. This includes all part-time and temporary work, as well as regular full-time, year-round employment.”

Related: 30 Percent of ‘Retirees’ Would Return to the Labor Force

That means the headline jobs number reported each month makes no distinction between someone who has a full-time job and someone who is working part time even though he or she would prefer to be working full time.

The agency does dig deeper, of course, and identifies those working less than full-time hours as “part-time for economic reasons” (PTER). Right now, though, that number is not coming down as quickly as most would like.

In a recent post on the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta’s macroblog, bank senior economist John Robertson and economic policy analysis specialist Ellyn Terry note, “As of July 2014, the number of people working PTER stood at around 7.5 million. This level is down from a peak of almost 9 million in 2011 but is still more than 3 million higher than before the Great Recession.”

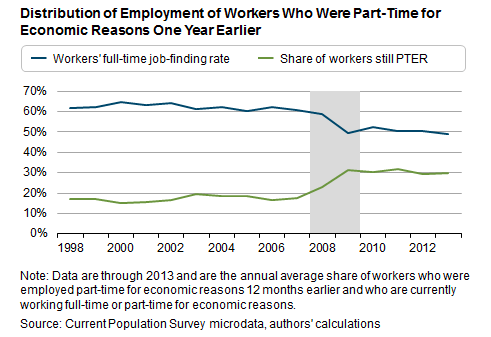

They also highlight data demonstrating that it is much harder for a part-time employee to move into full-time work now than it was in the years prior to the Great Recession. In 2006, if you had a part-time job, but wanted full-time work, you had a better than 60 percent shot at finding full-time work within a year. At the end of 2013, that same worker’s chances of finding full-time work were under 50 percent.

Related: Why Employers Are to Blame for the ‘Skills Gap’

Robertson and Terry find that the demographic characteristics of those struggling to find full time work, such as academic achievement, age, or gender seem to matter little in the trend.

“The phenomenon is pretty widespread, suggesting that the problem is a general shortage of full-time jobs rather than a change in the characteristics of workers looking for full-time jobs,” they write.

The U.S. economy is now, and has long been, reliant on consumer spending to drive growth. Even if they are nominally employed, consumers who make enough to pay the rent, but are constantly scrimping at the end of the month, are not in a position to help the country’s still-sputtering economy truly take off.

Robertson and Terry’s findings suggest it may be time for the financial press to stop obsessing over the headline jobs number, and instead start asking questions about whether the economic recovery is providing the kind of jobs the country needs to sustain long-term economic growth.

Top Reads from The Fiscal Times