“Just how low can stocks go?” In the wake of the financial crisis, The Wall Street Journal asked that question on March 9, 2009. That day, stocks tumbled again, with the S&P 500 hitting its lowest close since September 1996. The World Bank issued a forecast that the global economy would shrink that year for the first time since World War II. None other than Warren Buffett told CNBC that the economy had “fallen off a cliff.”

The Journal story that Monday morning suggested that the Dow Jones Industrial Average, which had already plunged more than 50 percent from its 2007 high, could sink another 25 percent. “As earnings estimates are ratcheted down and hopes for a quick economic fix fade, the once-inconceivable notion of returning to Dow 5000 or S&P 500 at 500 looks a little less far-fetched,” it said.

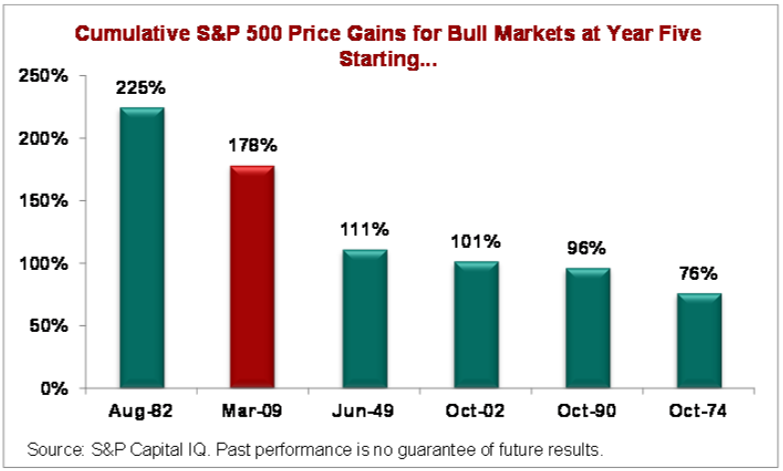

That’s what the bottom looked like. In the five years since then, stocks have staged a powerful rally that has lifted the S&P 500 index 178 percent and the Dow by 151 percent. It’s not the best five-year bull market we’ve seen — the rally that started in 1982 saw the S&P 500 gain 225 percent in five years, according to Sam Stovall, chief equity strategist at S&P Capital IQ — but it’s in a solid second place dating back to World War II.

The question now, of course, is how long can it last? Can the rally continue for another year or longer — and what will ultimately end the bull run? Some investors have already expressed concern that we’ve come too far too fast — and the extraordinary liquidity injected into the economy by the Federal Reserve has only fueled some investors’ doubts, especially now that the central bank has begun easing up on its support for asset prices.

Related: Bull Market Not Enough to Save Some Public Pensions

History may offer some lessons. Of the 11 previous bull markets S&P Capital IQ counts since 1945, the average rally lasted 4.5 years and only three have celebrated the six-year mark. At the same time, the current bull market is just the sixth longest since 1928, according to data from the Bespoke Investment Group.

That track record only matters so much, though. More important, analysts note, is that the current advance has been supported by improving fundamentals. “The gains that we’ve seen in the market have been thoroughly consistent with the gains that we’ve seen in what ultimately drives the equity markets in the long run, and that’s corporate earnings,” says Jeremy Zirin, chief U.S. equity strategist at UBS Wealth Management.

S&P’s Stovall echoed that point: “If you go back to either the prior bull market top or you go to the prior bear market bottom, in both cases earnings and price appreciation are exactly the same,” he notes.

That, Stovall says, means there’s a good chance the bull can keep running this year, if not at the pace that it did in 2013, when it gained nearly 30 percent. “Yes, we could see the market advance this year,” he says “However, I think it will go up by the amount earnings go up and not much more.”

Even if that’s the case, stocks could still suffer through a sharper pullback than the one we saw to start the year. “A correction is likely to occur this year for a couple of reasons,” Stovall says. “One, we have gone 29 months without a decline of 10 percent or more and the average time between such declines is 18 months.”

The history of midterm election years also points to the likelihood of a pullback, he adds. Every such year in recent history with the exception of 1954 and 1958 saw a decline of 9 percent or more, with the median loss being 19 percent.

If the market likes to “climb a wall of worry,” as the saying goes, it’s got plenty of material to build up that structure — or, alternately, plenty of factors that could derail the rally. Stovall, for one, lists a potential slowdown in earnings growth, the Fed’s tapering of bond purchases, deflation fears in Europe, geopolitical crises like the one in Ukraine. Even continued dysfunction in Washington or some surprise scare like a terror attack could weigh on stocks.

Let’s consider just one of those factors: The Fed. Even if stocks have largely shrugged off the taper so far, that doesn’t mean investors will continue to be unfazed by monetary policy shifts. A paper presented last month by a quartet of respected economists warned that the unwinding of the Fed’s easy money policies could still set off an investor “tantrum” similar to the one the markets experienced last summer, when the Fed first signaled its plans to wind down asset purchases.

“Our results suggest that bond markets could experience another tantrum – along the lines of that seen during the summer of 2013 – as extraordinary monetary accommodation in the United States is withdrawn,” the economists wrote.

Until that day comes, or the bull turns for some other reason, we can celebrate five years of strong gains and corporate earnings that look to be on more secure footing. “The big message this year from our team,” UBS’s Zirin says, “is that the bull market is not over because the earnings cycle is not over. The economic recovery is still gaining traction and just starting to look like it’s becoming more self-sustaining.” On with year six.

Top Reads from The Fiscal Times: