At a time when arguments over national debt and budget deficits are raging both in Washington and around the world, a group of economists at the International Monetary Fund decided to ask a provocative question: Does the amount of debt a country carries matter for its economic growth?

Using a data set that tracked the debt and gross domestic product levels of nearly every IMF member country back to 1875, economists Andrea Pescatori, Damiano Sandri, and John Simon examined whether there was a connection between countries’ debt-to-GDP ratio and their medium-term economic growth rate, asking particularly whether there was a threshold level of debt above which future economic growth would be damaged over a time frame of five years or more. They also investigated whether the debt ratio had an impact on the kind of growth countries experienced.

Related: Ending Debt Limit Uncertainty May Note Help the Economy

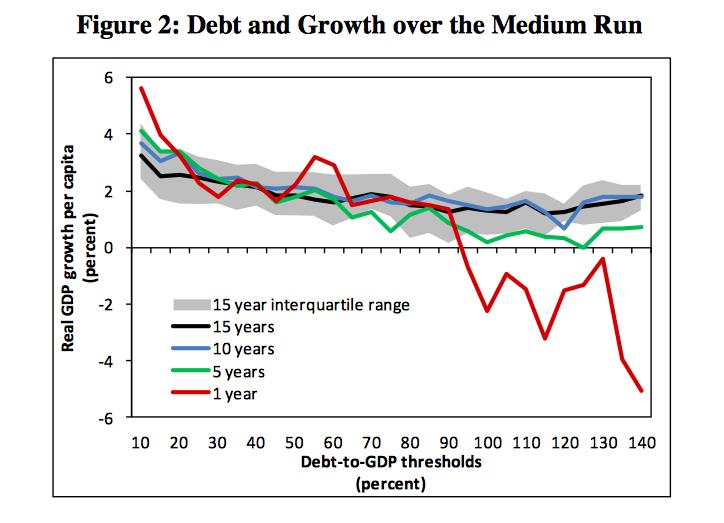

The surprising answer to the first question was no. The researchers, in their own words, found “there is no simple threshold for debt ratios above which medium-term growth prospects are severely undermined. On the contrary, the association between debt and growth at high levels of debt becomes rather weak when one focuses on any but the shortest-term relationship.”

However, they added, this is not to say that debt has no impact at all on growth.

“We have found some evidence that higher debt appears to be associated with more volatile growth,” the authors write. “And volatile growth can still be damaging to economic welfare.”

To be clear, the short-run effect of debt on growth was found to be significant. As debt-to-GDP approaches 90 percent, countries’ one-year growth rate goes to near zero, and plunges into negative territory at all levels above that. However, a five-year timeframe shows positive growth rates at nearly all debt-to-GDP ratios.

To be clear, the short-run effect of debt on growth was found to be significant. As debt-to-GDP approaches 90 percent, countries’ one-year growth rate goes to near zero, and plunges into negative territory at all levels above that. However, a five-year timeframe shows positive growth rates at nearly all debt-to-GDP ratios.

Related: The GOP Debt Ceiling Vote – Surrender of Strategy?

But once the lens is pulled back to look at long-term growth—meaning 10- and 15-year timeframes – the debt level shows little impact at all on growth rates.

What did have a measurable effect, however, was what the authors of the paper called the “trajectory” of a country’s debt.

Even over the long-term, a country’s expected growth rate at almost all levels of debt is significantly higher, by as much as a full percentage point of GDP growth per capita, if its debt ratio is declining rather than rising.

“In fact, even countries with debt ratios of 130–140 percent but on a declining path have experienced solid growth,” the authors write. “This observation suggests that the high debt itself is not causing the low growth in these episodes but other factors, associated with increasing debt, are more strongly implicated.”

Related: Unemployed and Hoping for Help from Congress

The authors caution that their paper alone is not enough evidence to base policy decisions on, but it at least suggests the possibility that, for the U.S., our current situation– U.S. debt held by the public is currently about 74 percent of GDP – doesn’t doom the country to poor medium-term economic growth.

However, the study points out that it would be better if the trajectory of the debt, which is expected to increase to 79 percent of GDP in 2024, were headed in the other direction.

Top Reads from The Fiscal Times:

- How Keynes Would Handle an Abnormally Slow Recovery

- CBO Future Shock: Economy Will Struggle for 7 Years

- Two Charts That Explain the 2014 Eurozone Crisis