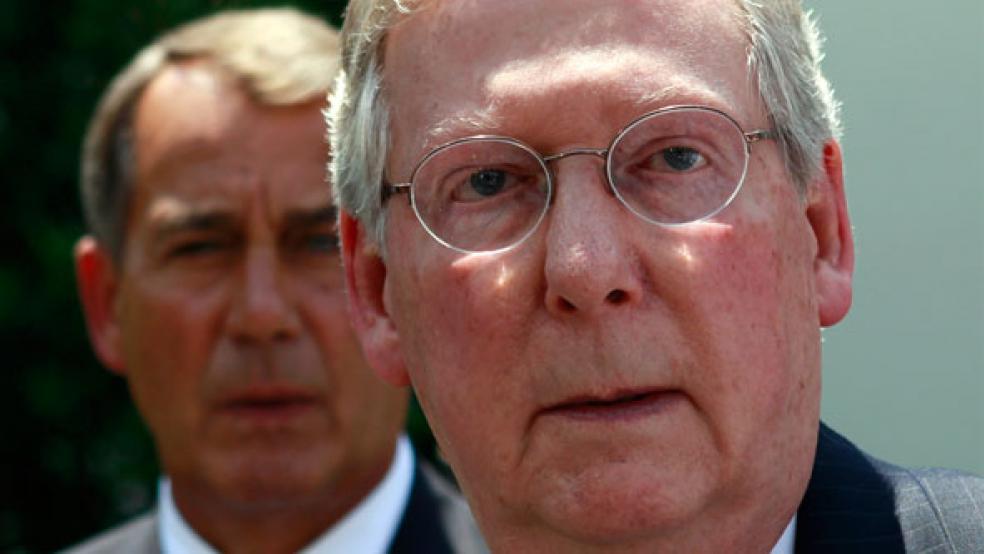

On paper at least, House Speaker John Boehner is the most important Republican in the country. He’s second-in-line to succeed the president of the United States and the taskmaster for a House Republican majority that’s determined to quash Obama’s agenda.

Yet in the wake of his politically disastrous handing of the fiscal cliff crisis last week, the affable Ohio Republican may have ceded the mantle of leadership to Mitch McConnell, the taciturn, 70-year-old dealmaker and leader of the Senate GOP minority.

It was the crafty Kentuckian who for the second time in two years came off the bench to hammer out a fiscal deal with Vice President Joe Biden—averting for the moment a serious blow to the economy.

While Boehner retreated to the sidelines to sulk after his troops rebelled against his own “Plan B,” McConnell recruited his former Senate colleague Biden to enter the fray four days before the New Year’s Day deadline. The Senate deal let Republicans escape Democratic attacks that the party would sacrifice the middle class in defense of millionaires. It raises taxes on incomes over $400,000, patches the Alternative Minimum Tax and postpones deep spending cuts in defense and domestic programs for at least two more months while Congress and the administration begin another round of talks on spending, entitlement reform and the debt ceiling.

“He thinks eight moves ahead,” House Appropriations Committee Chairman Hal Rogers, R-Ky., says of his long time friend McConnell. “We play checkers, he plays chess.”

McConnell, a one-time county executive who first won election to the Senate in 1984, did not rest on his laurels. He faces re-election in 2014—and anything that could be considered a tax increase would invite well-funded Tea Party opponents to enter the Republican primary.

After the Senate’s 89 to 8 vote in favor of the deal in the early hours of last Monday morning, McConnell dubbed the compromise “an imperfect solution” that nonetheless spared 99 percent of Americans a tax hike in the New Year. He resolved to address the need to increase the nation’s $16.4 trillion debt ceiling with deficit reduction.

“Now it’s time to get serious about reducing Washington’s out-of-control spending,” he said. “That’s a debate the American people want. It’s the debate we’ll have next. And it’s a debate Republicans are ready for.”

Or at least, a debate that McConnell is prepared to start. He is now in a much stronger position to shape negotiations than the wounded Boehner, who recently signaled he would no longer engage in one-on-one talks with President Obama, which repeatedly have gotten him into trouble with his party’s conservative wing. While McConnell himself acknowledges that last week’s eleventh hour compromise wasn’t a workable model for talks going forward on vital budget and debt issues, his entrée with the West Wing has improved.

Watch Mitch McConnell announce the deal on the "fiscal cliff."

McConnell is coming off a disappointing Republican showing in the 2012 Senate races, losing two seats after bold predictions the GOP would regain control of the upper chamber. But he commands far more allegiance among his conference than Boehner enjoys in the House. And in the case of Senate race losses, the extremism of some of the Tea Party candidates like Missouri’s Todd Akin and Indiana’s Richard Mourdock cost the party seats that should have been easy pickups.

By contrast, Boehner must tend to a dissenting group of conservatives who labored to remove him from the speakership last week. His thin 220 to 192 victory over Democratic leader Nancy Pelosi of California will likely keep him on a short leash, forcing Boehner to do far more consulting with rank and file members before signing on to deals with the administration and Senate leaders.

Rep. Tim Huelskamp, R- Kansas, one of three conservative rebels recently stripped of their prized committee assignment by the leadership, said that many Republicans who voted to reelect Boehner last week “are still very concerned with the direction of the conference.”

“I’m very afraid that if they continue to elect the same leadership and if they now continue to do the same things they did for two years, we could be looking at minority status for the Republican Party in two years,” Huelskamp told The Fiscal Times.

Lawmakers and political experts agree that despite its glacial pace and frustrating rules the Democratic controlled Senate is a far better venue for crafting the framework for major budget and tax agreements than the highly fractious, GOP-dominated House. The major obstacle to getting anything done in the Senate is the requirement for a 60-vote super majority – a tough obstacle to overcome that also gives McConnell and Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid, D-Nev., structural reasons to cooperate.

Yet even under the best of circumstances, McConnell and Reid may find it difficult to reach accommodations. McConnell turned to Biden for help in forging a fiscal cliff deal only after waiting the better part of last weekend for the Majority Leader to respond to his latest offer.

“The best chance for constructive work is for the Democratic and Republicans in the Senate to move forward on major issues,” said Sen. Ben Cardin, D-Maryland, a former House member. “Sen. McConnell and Sen. Reid both will play a very important role in that process. But I think that’s our best opportunity for the type of constructive resolution of major issues. . . . I think waiting for the House to send us over a reasonable bill is not going to happen.”

McConnell – who overcame polio as a child, graduated from the University of Louisville Law School and spent most of his adult life in government and politics – is a tough infighter who rarely shrinks from a battle. From almost the moment President Obama took office, McConnell pursued a course of action that earned him the moniker “Dr. No.”

The methodical McConnell held virtually all his GOP troops in line as he resolutely opposed all of Obama’s top priorities — from the $787 billion economic stimulus package to the sweeping health reform measure to legislation overhauling the rules governing Wall Street. He told the National Journal in October 2010 that his top political goal was to make Obama a one-term president; he didn’t want the president to fail—he wanted him to change and meet Republicans halfway on big issues.

He repeatedly intervened -- in December 2010, August 2011 and last week -- to resolve fiscal and budget disputes that threatened to shut down the government, force a default on government borrowing or take the country over a fiscal cliff of historic tax increases and spending cuts.

“Mitch has been a player when we’ve had crises,” former Sen. Richard Lugar, R-Ind., told the Fiscal Times. “The country was very fortunate that McConnell and Biden found each other. But I think Mitch is going to be just as important as we approach now the next fiscal cliff– the debt ceiling, and all that means.”

Josh Boak of The Fiscal Times contributed to this report.