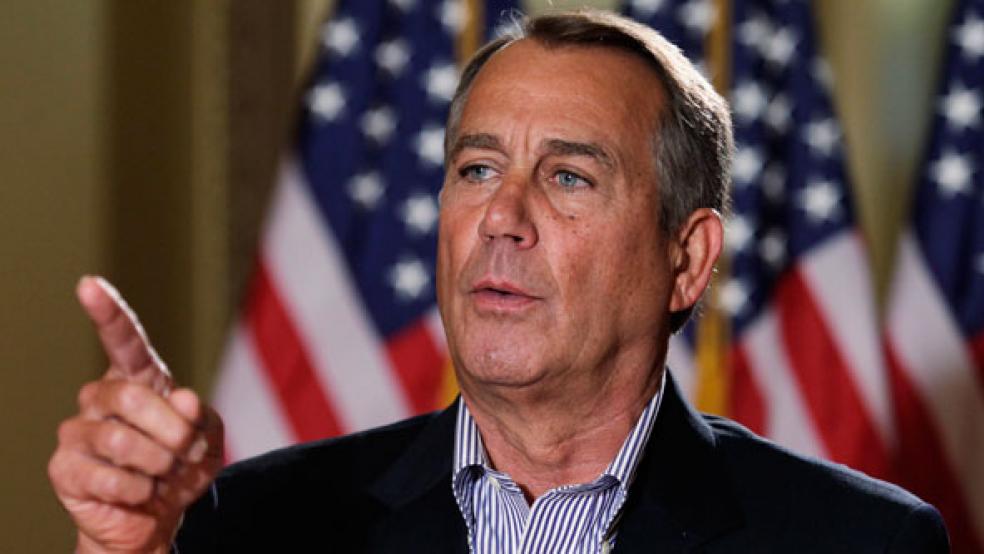

In a remarkable display of political jujitsu during the fiscal cliff talks, Republican House Speaker John Boehner renewed his complaint Tuesday that President Obama has yet to spell out his ideas for spending cuts and entitlement reforms. At the same time, Boehner refused to disclose the details of his latest counteroffer.

The public drama betrayed the extent of the private wrangling behind closed doors with less than three weeks before Congress is scheduled to adjourn for the year. Obama had privately sent congressional Republicans an amended proposal on Monday that scaled back his request for additional revenue by $200 billion to a new total of $1.4 trillion over ten years, CBS News reported.

Without disclosing the existence of that offer, Boehner took to the House floor on Tuesday to attack it as disturbingly vague on spending reductions.

“We’re still waiting for the White House to identify what spending cuts the president is willing to make” as part of Obama’s “balanced approach,” Boehner said in a brief midday floor speech. “Now if the president doesn’t agree with our approach, he’s got an obligation to put forward a plan that can pass both chambers of the Congress. Because right now, the American people have got to be scratching their heads and wondering when is the president going to get serious.”

Only hours later on Tuesday, it turned out the kettle was calling the pot black. A Boehner spokesman revealed that the GOP had also submitted a fresh bid but declined to outline the specifics other than to say it would “achieve tax and entitlement reform to solve our looming debt crisis and create more American jobs.”

The latest GOP offer doesn’t represent major movement on taxes, with Boehner still offering $800 billion of fresh revenue primarily derived by eliminating deductions and closing loopholes. And the new Obama proposal keeps the same spending cuts as the earlier bid that was based on the administration’s 2013 budget plan that’s designed to trim the debt by about $4 trillion over the next decade through a combination of tax hikes, savings, and program cuts.

The major remaining stumbling blocks to a deal appear to be the Republicans’ refusal to raise the top tax rates on the wealthiest two percent of Americans and Democratic objections about the scope of long-term reductions in Medicare and Medicaid spending. Only a few Republicans, including Rep. Tom Cole of Oklahoma, Sen. Bob Corker of Tennessee, and Sen. Tom Coburn of Oklahoma, have publicly conceded that the GOP will have to go along with some rate increase to placate Obama.

Corker and Sen. Lindsey Graham, R-S.C., said yesterday that, if need be, the Republicans would once again use the debt ceiling as leverage to extract major entitlement savings from the president. –“The only way I would make the debt ceiling part of a year-end deal is if it had significant entitlement reform,” Graham said. “Then, if we don’t get significant entitlement reform in the end of the year deal, then the next place to get it” is when the Treasury exhausts its borrowing authority by mid February.

“The president is going to be in for a rude awakening if he thinks he’s going to get the debt ceiling increase without addressing [entitlements and] lowering debt,” Graham told The Fiscal Times.

Boehner’s “show me your cuts” plea echoed loudly throughout the Capitol and in many corporate suites throughout Washington yesterday, as Republican lawmakers and some of their business allies demanded that the focus of the negotiations shift from how much in new revenues should be raised to what can be done to slow the growth of spending on entitlement programs.

“For all the president’s talk about the need for a balanced approach, the truth is he and his Democratic allies have simply refused to be pinned down on any spending cuts,” Senate Republican Leader Mitch McConnell of Kentucky complained as talks to try to head off nearly $600 billion of economic-jarring spending cuts and tax increase continue between the White House and congressional leaders.

But the problem isn’t that the president won’t show his hand. Obama’s fiscal 2013 budget plan and other documents provide plenty of details on how he would slow the rate of growth of major government programs and entitlements. The problem is that the Republican leaders don’t like what’s in that plan and couldn’t sell it to their rank and file members if they tried.

White House press secretary Jay Carney pointed out that the 246-page budget the administration unveiled last February has a "higher degree of specificity than we have seen by far from the Republicans."

The president’s budget contains $362 billion worth of Medicare savings over 10 years, of which 42 percent would come from paying less for drugs for low-income recipients. Obama’s budget also reduces Medicare payments for bad debts ($24 billion) and raises income-related premiums for higher-income beneficiaries beginning in 2017 ($30 billion), White House officials wrote in a Tuesday blog post.

GOP aides have floated the idea of raising Medicare eligibility to 67 from 65 and instituting a form of means testing. But what conservatives in Congress really seek are structural changes that prevent Medicare costs from erupting due to baby boomer retirements after 2022 – a period outside the decade-long timeline being negotiated.

According to a recent analysis by Steven Rattner, a private equity investor and the former auto industry advisor to the Treasury Department, Obama’s long-term deficit reduction strategy is a mix of 47 percent tax increases, 17 percent entitlement savings, 19 percent reductions in discretionary spending on government services and programs, and 17 percent miscellaneous savings. Boehner’s approach, by contrast, is a mix of 22 percent increased revenues, 31 percent entitlement cuts, 31 percent discretionary savings and 16 percent all others.

The complexity of achieving any consensus was exemplified by the Business Roundtable’s push Tuesday for a credible deal between lawmakers. The Washington-based trade association sent lawmakers a letter signed by 158 CEOs that backed down on its initial recommendation that all Bush-era tax cuts – including those for the wealthiest -- be extended for a year so that broader reforms could be introduced.

“Compromise will require Congress to agree on more revenue – whether by increasing rates, eliminating deductions, or some combination thereof – and the administration to agree to larger, meaningful structural and benefit entitlement reforms and spending reductions that are a fiscally responsible multiple of increased revenues,” the letter said.

But when many of the CEOs were asked about the reversal on taxes during a conference call with reporters, they stressed the importance of not reading too much into the details of the letter—and that their goal was not to be “prescriptive.” That term had an unintentional double meaning, since one of the crucial reforms to Medicare embraced by Obama involve reducing payments to pharmaceutical companies—which would likely hurt the profits of some Business Roundtable members.

John Engler, the association’s president, said that option—which would reduce the deficit by $137 billion over ten years—fails to address the big picture. “I don’t think it’s central to the principled compromise we’d like to see now,” Engler said during the call.