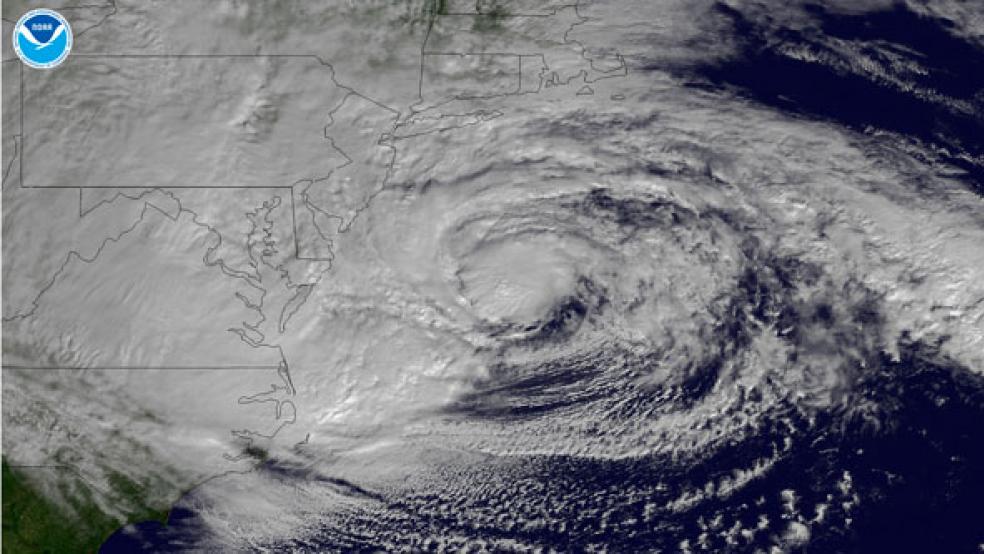

If there was a ray of sunshine in the aftermath of Superstorm Sandy’s devastating sweep across the northeastern seaboard last week, it was the sight of American politicians finally beginning to talk about climate change.

“Our climate is changing,” New York mayor Michael Bloomberg wrote in an op-ed endorsing President Obama for reelection because of his willingness to tackle the issue. “And while the increase in extreme weather we have experienced in New York City and around the world may or may not be the result of it, the risk that it might be – given this week’s devastation – should compel all elected leaders to take immediate action.”

That came just 24 hours after New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo noted “there have been a series of extreme weather events. That is not a political statement; that is a factual statement. Anyone who says there is not a change in weather patterns is denying reality.”

As Bloomberg noted, there is no need to immediately engage the issue of man’s responsibility or whether burning fossil fuels is to blame. The incontrovertible fact is that the polar ice cap and mountaintop glaciers are melting, filling the rising oceans with warmer waters. The result is that major storms – both inland and those that batter seaside cities and towns – are growing more intense. Political leaders of all stripes are going to have to come to grips with that reality, and quickly.

TARGET: NORTH AMERICA

Over the past year, warnings about the growing intensity of storms have piled up faster than the yachts and fishing vessels behind President Obama and New Jersey Gov. Chris Christie, who linked arms while vowing to rebuild the more than 100 miles of heavily populated coastline that had just absorbed the most devastating storm damage in recorded history. Less than a fortnight before the storm, Munich Re, the world’s biggest reinsurance firm, declared that “nowhere in the world is the rising number of natural catastrophes more evident than in North America.”

Its latest study showed that weather-related “loss events” had quintupled over the past three decades – costing over 30,000 lives and causing in aggregate over $1 trillion in damages in inflation-adjusted dollars. While it will be years before the final bill for Sandy comes due, it took only 48 hours for forecasters like Eqecat and Moody’s Analytics to raise their damage estimates from $10 to $20 billion to $30 to $50 billion. If those early projections follow the same upward path as Hurricane Katrina, Sandy’s damage will soon rival the Gulf Coast storm’s eventual $125 billion cost.

It wasn’t just insurers sounding the alarm bells. A U.S. Geological Survey report issued in June warned that “rates of sea level rise are increasing three-to-four times faster along portions of the U.S. Atlantic Coast than globally.” Since 1990, the 600 miles from Cape Hatteras, N.C. to north of Boston – which the report called “the hotspot” – rose 3/4 to 1 ½ inches compared to less than a third of an inch in most other areas of the globe. The study projected that over the rest of the 21st century, the North Atlantic will rise at least another foot with some scientists saying the increase could be more than three feet.

Study author Asbury Sallenger, an oceanographer with the USGS office in St. Petersburg, told The Fiscal Times that warmer, higher ocean water increases the height of breaking waves and volume of storm surges even when storms are similar to those of the past. “Scientists discussed long before the issue was in your face like it is now that there were reasons to adapt to the kind of storms you’re seeing,” he said. “Sea level rise is going on and that exacerbates the impact of any storm.”

That analysis is supported by the long-term pattern of Federal Emergency Management Agency disaster declarations and awards. The smoking gun doesn’t lie in the steady increase in the number of disasters declared since the Stafford Act was passed in 1988, which liberalized the ability of governors to request and presidents to grant aid to counties or states hit by natural or unnatural disasters (New York was declared a disaster area after 9/11).

Population growth, people’s propensity to build in riskier but highly desirable areas and even election year politics – not climate change – has led to much of that increase, according to Scott Robinson, a professor in the school of public service at Texas A&M University. “As a nation, we are moving into hurricane-prone areas,” he said. “Our zeal for development has put assets in places that are prone to flood.”

Yet Steven Daniels, a professor of public policy at California State University at Bakersfield, found an interesting pattern in the data. The cost of the typical storm that leads to federal disaster status hasn’t gone up, either. Rather, it is outlier event – like Katrina or Sandy – that is driving rising federal expenditures on disasters. “We’re having just as many big catastrophes as before,” he said. “But when we get those, the effects are much bigger.”

As the intensity and damage caused by storms continues to rise, the public will demand protection. The immediate responses from centrist Democrat Cuomo, independent Bloomberg and conservative Republican Christie clearly showed that.

Even as New York marathoners learned their Sunday race had been canceled, a lively debate broke out on the website of the city’s hometown newspaper about the proper strategy for living next to bodies of water that now appear more menacing that sublime. “Should New York Build Sea Gates” asked The New York Times’ Room for Debate page.

Six contributions offered proposals ranging from a resounding yes to a qualified no, which instead suggested hundreds of smaller projects to protect critical infrastructure. The one answer they all had in common was the need to spend tens of billions of dollars on projects that had no obvious financing prospects.

“We have to do something,” said Robert Puentes, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution’s Metropolitan Policy Program. “Criticism that we can’t afford it isn’t accurate. We’re still the richest country on the planet. It’s a question of priorities.”

During the presidential campaign, the two parties were sharply divided over how to finance major new federal initiatives for critical infrastructure projects. Democrats and President Obama supported establishment of a new infrastructure bank seeded by taxpayers whose bonds would be retired by fees from the projects. Republicans and challenger Mitt Romney have suggested turning everything over to the private sector, which would build, own, operate and maintain the new facilities.

But neither approach is realistic in the face of the growing storm protection needs of coastal cities and towns. Placing the entire burden on sea-going vessels passing through the gates or on local taxpayers is absurdly prohibitive.

For years, the American Society of Civil Engineers has been warning about the deteriorating state of its roads, bridges, sewers, waste water treatment facilities and other critical infrastructure systems. Superstorm Sandy and the now unquestioned march of climate change has just added the pressing needs of the nation’s coast communities – including its largest city – to the mix.