Republican presidential nominee Mitt Romney has a three-day bus trip planned through Ohio this week, and it comes none too soon: Ohio, with its 18 electoral votes in the nation’s industrial heartland, looms as the quintessential battleground state, and right now President Obama holds a seven percentage point lead.

Obama has swung through Ohio more than any other state, except for Virginia, and experts say that if the election were held today, the president would likely win there and in other blue collar states, including Pennsylvania and Michigan. With the auto industry humming again in Ohio after the administration bailed out General Motors and Chrysler, Obama has repeatedly made the case to Ohioans that he pulled their economic chestnuts out of the fire while Romney attacked the plan. The former Massachusetts governor has been haunted on the trail for penning a November, 2008 New York Times editorial that called for letting the companies go through a “managed” bankruptcy and suggested that a “bailout check” would cause the sector’s demise.

“When there were some who said just ‘let Detroit go bankrupt,’ when there were folks who were willing to walk away from all the jobs that are supported here in Ohio by the auto industry, I bet on American workers,” Obama told voters in Columbus last Monday, using a line that appears with some variation in practically all of his rustbelt stump speeches.

Ultimately, both companies did file for bankruptcy, but fewer jobs were lost than expected under the potential disaster scenarios and their recovery was accelerated by the government intervention.. It’s an easy pitch for Obama with the Chevrolet plant in Lordstown, Ohio, turning out the top-selling Cruze compact around the clock, while Chrysler continues to crank out Jeeps in Toledo.

“Obama has a very compelling argument to make that his actions in bailing out the auto industry were central in not only the good times the auto industry is experiencing right now but also avoiding catastrophe,” said David Cohen, a professor of political science at the University of Akron. “Because one in eight jobs in Ohio are somehow connected to the auto industry.”

SKELETONS OF CLOSED FACTORIES

But even as Obama gets credit from Buckeye voters for the $80 billion bailout plan, Romney has drawn thousands to rallies and blasted the airwaves with arguments that the dollops of stimulus spending never delivered anything close to the promised recovery. The skeletons of closed factories still litter parts of the state, and incomes averaged $37,791 last year—almost $4,000 below the national average, according to the Bureau of Economic Analysis.

The former Massachusetts governor has tailored his message to Ohio’s blue collar identities by claiming he would stop China from pegging the value of its currency at an artificially low rate to the dollar, causing the departure of assembly line jobs for plants in Asia. In speeches to Ohio voters, he castigates Obama for the 23 million Americans who are either jobless or underemployed.

“If you have a coach who’s 0-23 million, you say it’s time to get a new coach,” Romney told a crowd in Cincinnati this month. “We’ll crack down on China and any other cheaters.”

With almost a week before absentee balloting starts, the question is whether the Ohio cities along Lake Erie respond to Obama’s description of a blue-collar economy restored under his watch , or if Romney’s pledge that an aggressive trade policy will stop the practice of off-shoring jobs to China can expand his GOP base beyond Ohio’s rural counties.

Some Republicans have expressed concern that Romney has not been spending more money or appearing more frequently in rural counties where he needs a strong turnout to win the state – and where his “47 percent” comments threatens to undercut support among working-class voters otherwise inclined to vote for him, according to The New York Times.

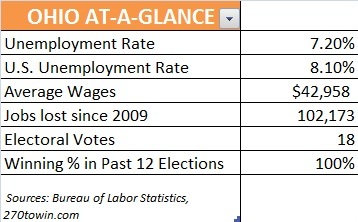

Ohio voters have backed the winner in the past 12 presidential elections, with a mix of Democrats and Republicans that make it a perpetual swing state. Obama beat Arizona Sen. John McCain there 51.5 percent to 46.9 percent in 2008, a 262,224-vote margin of victory.

ENERGY AND TECH LEAD THE WAY

Economic turmoil is nothing new to the state—which has endured decades of politicians pledging that they will succeed in creating an industrial rebirth where their predecessors have failed. But what makes Ohio unique in 2012 is an economic comeback that—for the first time in decades—appears stronger than the rest of the country. Manufacturing jobs are up 3.1 percent this year, as the prospect of energy jobs from shale oil and gas has emerged alongside collaborations involving the state’s universities and research institutions that are jumpstarting the formation of tech companies.

The critical place to watch will be the northeastern counties surrounding Cleveland, said Cohen, who is also a fellow in the Ray C. Bliss Institute of Applied Politics.

Obama won the Democratic stronghold of Cleveland’s Cuyahoga County, which has a black population of 30 percent, by 458,000 votes in 2008. “And so for Romney, he’s got to cut those margins down in those urban counties,” Cohen said.

One stat perfectly illustrates their conflicting views of the economy: 7.2 percent, the state unemployment rate. It peaked at 10.6 percent in the middle of 2009—much higher than the national average—and then plunged at a speed that leaves Buckeyes much better off than the rest of the country.

Obama credits the rebound to his administration’s rescue of General Motors and Chrysler, a multi-billion dollar intervention that just might have saved the U.S. automakers from the scrap heap. But some of the improvement with the unemployment rate actually came from a withered labor pool—and Ohio has yet to heal both in terms of its economy and identity from a decline in factory employment that politicians first pledged to stop a generation ago.

OVER 100,000 JOBS LOST SINCE 2009

Labor Department records show Ohio had 102,173 more jobs when Obama assumed office in 2009. More than 200,000 Ohioans simply dropped out of the workforce during his tenure, a sign of the underlying gloom that Romney has capitalized on.

“After four years, it’s clear that President Obama’s policies aren’t fixing the problems—they’re making them worse,” Romney said in a speech last month in Chillicothe. “And that’s why Ohio will lead the way by electing a new president on November 6. For the first time, most Americans believe our best days are behind us.”

The former Massachusetts governor has broadcast ads pledging to label China as a “currency manipulator,” an argument with enough traction that Obama announced a World Trade Organization complaint against the world’s biggest manufacturer last week in Ohio.

The flaw in these arguments is that they reduce Ohio’s economy to an election-year timeframe and seemingly stark political choices. Factory layoffs predate the rise of China, and the state government and civic organizations launched partnerships and programs to re-orient the Ohio economy decades ago.

Ohio’s recovery has outstripped the rest of the country, in part, because of what’s not occurring in Washington: quiet cooperation between parties for an extended period of time, said Brad Whitehead, president of the Fund for Our Economic Future, a foundation focused on stimulating regional economic growth.

“What is happening on the ground is that we are finding ways to work pragmatically across parties and with, I think, some pretty enlightened public policies at the state level,” Whitehead told The Fiscal Times. “Both parties can take credit, including the Obama auto industry bailout and the policies of Republican Gov. John Kasich, who is very focused on transactional excellence in supporting companies and deals. And he will go anywhere to close a deal.”

For example, Bob Taft established the Third Frontier program while governor in 2002 to use proceeds from the sale of bonds to help incubate new tech companies and innovations. His Democratic successor Ted Strickland continued the initiative, which claims to have created, attracted or capitalized more than 700 companies.

Whitehead said that ten years ago there was a lot of “hand wringing about the future” – pretty much a period of despondency. “Whereas now,” he said, “there is a sense that Northeast Ohio and Ohio does know where it’s going.”