Mitt Romney’s top economic advisers last week painted a clear portrait of the policy initiative the Republican presidential hopeful plans to use to restore robust growth to the U.S. economy. In a phrase: more tax breaks for business.

Writing in the Wall Street Journal, former Texas Sen. Phil Gramm, one of the leaders of the Tea Party movement, and Glenn Hubbard, a Columbia University business professor and top economic adviser to the Romney campaign, said the former Massachusetts governor, if elected, would enact the same policies as those enacted by President Ronald Reagan shortly after he took office in 1981. “Particularly powerful are (Romney’s) proposals to reduce marginal tax rates on business income earned by corporate and unincorporated businesses alike,” the two advisers wrote. “His goal, like Reagan’s, is to make it profitable to invest in job creation.”

The two advisers accused President Obama of failing to understand business when he said the president’s job is “not simply to maximize profits.” They said, “Jobs are sustainable only when profits are sustainable….The American economy was built on the profits earned by serving consumers, and it will only be saved by earning profits.”

Gramm and Hubbard make an obvious point. Businesses that fail to make money not only don’t hire new employees, they dismiss workers when revenues fall. Business profits plummet in recessions and payrolls follow shortly thereafter.

But to suggest that President Obama has somehow held back business profitability during what has been a tepid recovery from the Great Recession simply ignores what is taking place on corporate balance sheets. According to an analysis by Moody’s Analytics for The Fiscal Times, profitability in non-financial firms surged in recent quarters to 15 percent, a level not seen since the late 1960s.

The rating firm’s survey of the 1,100 non-financial companies it follows also found that they were sitting on cash hordes in excess of $1.24 trillion last December. Apple alone was sitting on nearly $100 billion. The entire corporate sector had over $2 trillion in cash. Alas, robust hiring has not followed in the wake of surging profits. “Giving more tax breaks to corporations that are awash in cash is not going to lead to anything,” said Joseph Stiglitz, a Nobel Prize-winning economist at Columbia University after serving as President Clinton’s chief economic adviser and top economist at the World Bank. “It’s a lack of demand that’s really impeding investment.”

Stiglitz is among the growing number of economists and business leaders who believe that lagging income, whether for people who already have jobs or those who are still un- or under-employed, has become the central problem facing the U.S. economy. Stagnant income explains why the rebound has failed to become self-sustaining, they say.

Millions of Americans who never lost their jobs during the downturn have gone years without a raise. Others remain on short hours. If self-employed, they find less work. Millions more, especially in the public sector, are seeing sharp cutbacks in their pensions and benefits, which leads them to cut back on discretionary spending. Most householders have seen declines in their home values and retirement accounts, triggering a negative “wealth effect” that also holds down spending.

Some political analysts have suggested last week’s Wisconsin recall election hinged on voters who are no longer willing to pay for public employee pensions and benefits they no longer enjoy. A third of union households voted for Gov. Scott Walker, the Republican candidate who became a national hero on the right by forcing public employees to pick up a larger share of their own benefits – something private sector employees have been doing for years. Public sector austerity – the other major plank in the Republican Party economic platform besides tax breaks for business and one they plan to enforce at the federal level – sounds like everyday life to them.

Liberal Democrats have tried to counter the politics of austerity and envy by focusing on income inequality. The Occupy Wall Street movement rhetorically pitted the one percent versus the 99 percent and emboldened Democratic politicians across the political spectrum to call for taxing the rich to help pay for needed public services like research and education.

New books such as Stiglitz’s The Price of Inequality: How Today's Divided Society Endangers Our Future and New Republic writer Timothy Noah’s “The Great Divergence: America’s Great Inequality Crisis and What We Can Do About It” paint the income gap as the major roadblock to renewed prosperity. They also say it is undermining democracy.

The nation’s wealthiest citizens, unleashed by the Citizens United decision, are pouring enormous sums of cash into this year’s political campaigns. Last month, Romney outraised the president, the best campaign fundraiser the Democratic Party has ever known. “There is a connection between economic inequality and political inequality,” Stiglitz said.

However, focusing on income inequality is a tough sell in the U.S., which culturally imagines anyone can get rich with enough luck and pluck (even as recent surveys have shown that the U.S. now has the least social mobility among all advanced industrial nations, a sharp reversal of historical pattern that viewed Europe as “class bound”). Most Americans are willing to say, “live and let live” to the folks sailing in yachts when their own boats are rising.

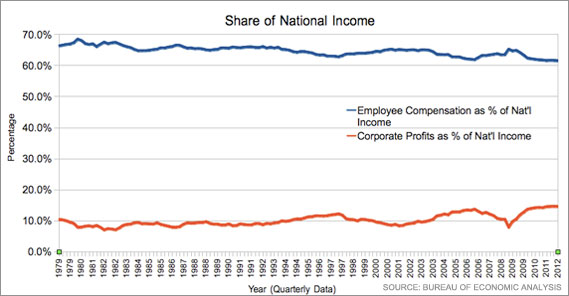

So why aren’t all boats rising today? Not only is the income gap growing, but both the rich and poor are dividing a shrinking pie. Why? A growing share of income is going to the same corporate sector that Romney wants to shower with more tax breaks. The share of all income going out in wages, salaries, dividends, interest and capital gains, which includes everyone’s pay from the chief executive officer to the lowly janitor, is declining as a share of national income and has been for over 30 years. According to the latest quarterly report from the Bureau of Economic Analysis, employee compensation has fallen to 61.6 percent of total national income, down from 66.3 percent when Ronald Reagan took office.

Corporate profits as a share of total national income, on the other hand, have surged to 14.6 percent from 10.4 percent over the same time period." Lay that on top of the growing income gap in the wage sector and what’s left is average employees scrapping over a smaller slice of a smaller pie.

In such an environment, which is very different from when Ronald Reagan took office but one he helped to shape, Romney’s tax program is the exact opposite of what is needed. It also contradicts the wisdom first preached by one of America’s greatest business leaders. In another era, Henry Ford, after inventing the modern assembly line, recognized that he badly needed customers for the millions of cars that could roll out of his factories every year. So in 1914 he offered his employees the then unprecedented salary of $5 a day.

He “reasoned that since it was now possible to build inexpensive cars in volume, more of them could be sold if employees could afford to buy them,” the company noted in its official history. “The $5 day helped better the lot of all American workers and contributed to the emergence of the American middle class.”

An increasing number of economists are echoing that sentiment for today’s environment. Aaron Smith, a senior economist at Moody’s Analytics, said, “What is clear going forward is that in the absence of debt and government support, we’re going to need the labor share to stop declining if consumers are to regain their prowess as drivers of the U.S. economy.”