A radical plan to slash public employee pension benefits gets voted on by the residents of Silicon Valley's San Jose on Tuesday - a decision that could set an important precedent for many other cities, not only in California but across the nation.

The nation's 10th-largest city is also one of the wealthiest, but over the past several years it has cut its municipal workforce by a quarter, laying off cops and firefighters, shuttering libraries and letting street repairs fall by the wayside.

The problem? Mayor Chuck Reed says it's simple: Retiree benefit costs eat up more than a quarter of the city budget - and are growing at a double-digit rate. The solution he is pushing at the ballot box, after city council approval, would slash benefits for workers, increase employee contributions - and almost certainly prompt a precedent-setting legal challenge from the public employee unions.

RELATED: Ten Insanely Overpaid Public Employees

"The best metaphor is cancer," said Reed, a Democrat known as more of a technocrat than a firebrand, who is now cast as public enemy No. 1 by public employee unions. "It started a long time ago, it goes for a long time, and then it becomes life-threatening." It's a challenge other cities in California will soon face. "Our problem is nearly universal in the state," he added. "It's just a question of timing."

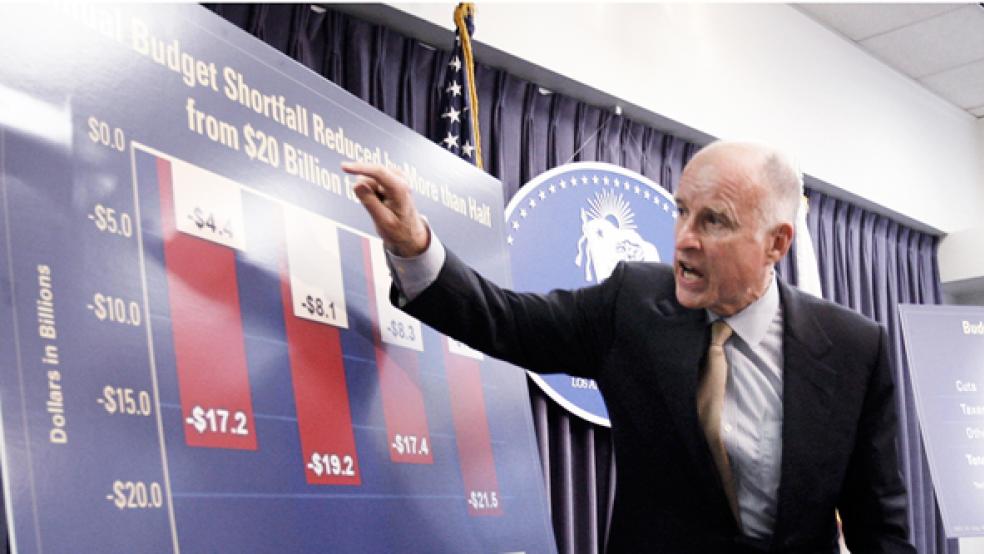

Public finance woes are nothing new in California. The state budget deficit stands at an estimated $15.7 billion for next year, requiring further cuts in state services and, if Governor Jerry Brown has his way, higher income and sales taxes. Local governments and school districts have struggled for years to make ends meet.

The pension problem, though, may be the mother of all budget issues - for California, for its cities and counties, and for other states and municipalities across the nation. The main California state retirement systems have a total shortfall in pension-plan funding of close to half a trillion dollars, a Stanford University study estimated. The bill is not due at once, but payments on it grow steadily and can eventually squeeze out even basic services. Public officials like Reed, and academics who have studied the issue, say the day of reckoning is nigh.

San Jose is not the only city making tough choices. In San Diego, voters will also be asked to approve a pension-cutting ballot initiative on Tuesday. In Stockton, city officials, unions and creditors are engaged in a mediation process aimed at avoiding a municipal bankruptcy - and public employee pensions are an achingly large part of the problem.

San Jose, San Diego and the counties of Kern, San Mateo and Santa Barbara are among the worst-off of municipalities with their own retirement systems, based on calculations in the Stanford study; all pay double-digit percentages of their annual budgets to pensions and all face double-digit rates of increase, among other issues. The city of Los Angeles was only marginally healthier than the bottom of the pack.

RELATED: The 10 Best and Worst States for Small Business

Meanwhile, the giant California Public Employees' Retirement System (CalPERS), the largest public pension fund in the country, has been engaged in a tortured debate about whether its rate-of-return assumptions are too optimistic. The CalPERS plan covers state workers and dozens of cities that voluntarily joined its system.

It recently cut its annual return assumption to 7.5 percent from 7.75 percent, which would raise the shortfall it previously had estimated at $85 billion to $90 billion. CalPERS says it has easily met its return target for 20 years, but Stanford's Joe Nation and other economists say a lower rate would better reflect the uncertain outlook for markets and a century-long record of market returns. On Friday the Dow Jones industrial average fell to its lowest level in 2012 - dropping into negative territory.

That explains why Nation calculates the collective shortfall at CalPERS, the smaller California State Teachers Retirement System and a state university plan at half a trillion dollars - he assumes lower returns than do systems run by the state and cities like San Jose.

It's some consolation for California, perhaps, that the bill mounts slowly - and other states are in even worse shape.

"The pension situation in California is by no means the worst," said Douglas Offerman, an analyst at Fitch Ratings. "We rate California lower than we rate any other state. We do not rate it at that level because of its employee obligations."

GOOD TIMES, BAD TIMES

The roots of the pension crisis can be traced to the 1990s, when CalPERS, flush with cash from the stock market boom, pushed state legislation to raise retiree benefits, including a retroactive bump for state employees.

The 1999 law, adopted overwhelmingly by legislators on both sides of the aisle, knocked five years off the retirement age for many workers, bumped up payments - or both. Every career government worker could quit at 50 or 55 with a solid, and sometimes lavish, pension. Because CalPERS also manages pensions for so many local governments, the law set off a bidding war across the state, with employees and their unions insisting on parity, or better, with neighboring jurisdictions.

"That eventually washed its way down into local government, and by 2006 our public-safety employees had 90 percent retirement benefits at age 50," Reed recalled. Half a century earlier a San Jose policeman had to work until age 55 to retire with half his pay. Stanford's Nation did a rough calculation to figure out how much it would cost to get comparable retirement benefits in the private sector. "You'd have to start putting away half your salary, starting at 25," he said.

California, the most populous state, also has some of the most generous benefits in the country, says Alicia Mannell, director of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College. She is more optimistic than Nation about California's next few years - she says the shortfall may shrink - but she agrees the state has blundered.

"These plans get so expensive - California has the most expensive plan - that people are going to have to realize that if those commitments are fulfilled, then other things are not going to get done," she said.

Critics say a big part of the problem is a fundamental conflict of interest in the way the pension plans are governed. Pension fund boards are dominated by beneficiaries - workers and retirees. A six-member minority of the 13-member CalPERS board represents workers and retirees. But the minority also holds the chairmanship, and the entire current board are CalPERS members, due to their state service.

The directors of the nation's largest public pension fund are not required to have financial backgrounds, either, although the fund says it gives training to the board. Beneficiaries have an incentive to keep the plans solvent, but with a state constitutional guarantee they can rest assured that their retirement benefits will get paid. Meantime, the board members, themselves beneficiaries, also have an incentive to make the benefits as rich as possible - and the CalPERS board has focused substantial energy on raising benefits and enforcing the state guarantee of payment.

"The way pension systems have been run, to a certain extent, is legal corruption," said Nation, explaining the conflict of interest inherent in systems run by beneficiaries rather than those who pay the bills. Brad Pacheco, a CalPERS spokesman, pointed out that directors elected by members were a minority and that the entire board had a fiduciary duty. "When they make a decision, it is not in self-interest but through the lens of how the decision will benefit or impact our members, employers and taxpayers," Pacheco said.

San Jose faced what it saw as a conflict of interest in 2010. That year it expanded and reformed its pension boards, giving independent citizens with financial backgrounds, approved by the city council, majorities on both.

THE FIX

Scores of city and state unions already have bargained to cut the pension load, generally by creating lower-benefit plans for new hires, Pacheco said. But that's not going to ease the problem soon, economists say. The state and cities need to be able to cut benefits for current employees, concluded the state's Little Hoover Commission, which is charged with creating realistic solutions for tough problems in the state.

The commission recommended that state lawmakers point the way with legislation allowing contract changes that gave midcareer workers the benefits they had accrued but cut the level of benefits they would earn in the future - which unions say is not fair play. CalPERS has drawn a line in the sand, saying it will defend benefits, and there's been no major challenge yet. The city of Vallejo went bankrupt in 2008 but agreed to pay its pension obligations in full. Proposals by financially hobbled cities to cut costs "may lead only to additional litigation and administrative costs," CalPERS warned in a policy paper last year.

San Diego is focusing on future employees, who will go on a 401(k)-style plan, which is common in the private sector, if voters approve the measure on Tuesday. That would transfer the risks and gains of rising and falling markets to workers. But San Diego is not aiming to change plans for police officers, who generally get the highest benefits and can retire earliest, and the change doesn't affect current employees.

San Diego's plan represents the biggest fundamental change, while San Jose's would be the highest-profile effort to get employees to pay more. It would change the rules for all current employees. It wants to let city employees choose between switching to a lower-benefit plan or paying substantially more to keep current benefits.

San Jose's retirement costs rose to $244 million, or a quarter of its general fund budget in the fiscal year ending in June, and even with relatively optimistic investment return assumptions, the city expects retirement costs to hit $325 million four years from now, unless voters pass Mayor Reed's reform plan, known as Measure B.

The stakes are high for employees: The police union calculates that the ballot measure and previous changes could leave an officer paying more than 40 percent of his salary for retirement, a figure the city describes as a worst-case scenario but does not dispute. San Jose Police Officers' Association President Jim Unland thinks Mayor Reed is exaggerating the problem and is misleading voters about the legality of the plan. That said, Unland expects voters will trust their mayor and approve his plan.

If that happens, the battle is sure to move to the courts, where Unland expects it to remain for years. "In the end, we'll probably be right back where we are today," the police union president said.