The late Senator Russell Long of Louisiana once famously said of the political dilemma posed by tax reform: “Don’t tax you, don’t tax me, tax that fellow behind the tree!”

The storied Democratic chairman of the tax-writing Senate Finance Committee had few peers in devising clever ways to cut tax rates. And he was brilliant at weaving important tax breaks and deductions into the fabric of the federal tax code, ranging from the Earned Income Tax Credit and Child Support Enforcement Act to the Employer Stock Ownership Plans.

But once those tax breaks became part of the law, it was like pulling teeth to get them out of there. That’s what House Republican leaders are learning now, as they seek ways to offset the huge long-term cost of their major tax overhaul plan. Some of the largest and costliest of these deductions are among the most popular, including employer-provided health insurance, mortgage interest and 401(k) savings plans.

“When you begin to take away certain deductions, you are actually affecting people’s bottom line in taxes that are due,” said Bill Archer, a former Republican Ways and Means Committee Chairman. “And depending on the particular deduction, you are going to face enormous political difficulties. And I think they are going to be much bigger than many people in Congress believe right now.”

Tad DeHaven, a federal budget analyst with the libertarian Cato Institute agrees: “Every tax provision, just like every spending program, has a constituency. A lot of money and a lot of effort have gone into obtaining provisions for particular industries and folks. And getting them to agree to part with it is quite a difficult task. It’s Politics 101.”

Tax reform is a battle cry of both parties in a key election year. But how and when to try to overhaul the federal tax code – and pay for it without adding to the $15 trillion national debt -- is the overarching and perplexing questions hanging over Congress and the White House.

President Obama wants the wealthiest Americans and the oil and gas industry to pay more in taxes in exchange for cuts in Medicare, Medicaid and other domestic programs. Republicans and some moderate Democrats are pressing for adoption of a “revenue neutral” tax overhaul – along the lines of the last big tax reforms of 1986 – that would reduce individual and corporate tax rates and broaden the tax base by getting rid of many of the estimated 200 tax credits, deductions and other provisions currently on the books.

The House-passed GOP plan drafted by Budget Committee chairman Paul Ryan of Wisconsin would cut the top marginal tax rates for individuals and corporations from 35 percent to 25 percent and eliminate taxes on the foreign profits of U.S. based multinationals. But that would cost the Treasury a staggering $4.6 trillion in foregone revenue over ten years, according to the Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center. And that would come on top of the $5.4 trillion cost of extending all the Bush era tax cuts, as congressional Republicans and Republican presidential candidate Mitt Romney favor.

Ryan’s budget and tax overhaul scheme left it up to the Ways and Means Committee and its chairman, Dave Camp of Michigan, to come up with a laundry list of tax breaks that could be sacrificed, with the proviso that the committee couldn’t tamper with the preferential tax rate for capital gains and dividends.

ELIMINATE WHAT?

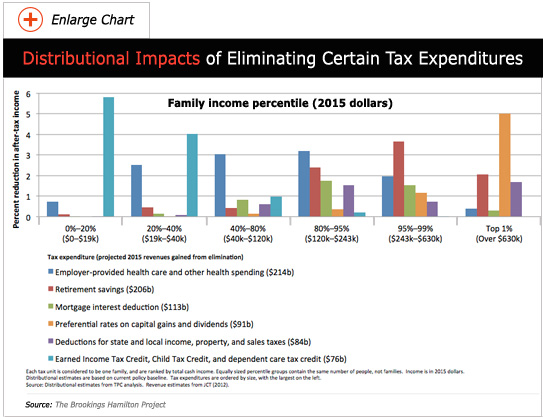

The couple hundred tax deductions and refundable tax credits currently on the books will cost the government as much as $1.3 trillion in foregone revenues this year, according to Treasury estimates. According to an upcoming report by the Brookings Institution’s Hamilton Project, Congress would have to eliminate all but about $200 billion a year in tax breaks, or roughly four fifths of their value, to reduce the top individual and corporate tax rates to 25 percent, according to the Washington Post.

“It’s an inexorable equation,” Sen. Charles Schumer, D-N.Y., told The Fiscal Times. “If they lower the top rate from 35 to 25 and say that capital gains and dividends must stay where they are, it is impossible to be revenue neutral without clobbering middle class exemptions that have broad support.

Among the biggest tax deductions with huge political constituencies are these:

• Tax-free employer-provided health care and other health spending constitutes the single largest tax expenditure: $214 billion a year.

• Retirement savings, including IRAs and 401(k) programs: $206 billion annually.

• Mortgage interest deductions on homes and second homes: $113 billion a year.

• Preferential rates on capital gains and dividends: $91 billion.

• State and local income, property and sales tax deductions: $84 billion.

• Earned income, child and dependent care tax credits: $76 billion.

Last weekend, Romney entered the tax-reform fray accidentally when reporters overheard him telling people at a Republican fundraiser that he might be willing to eliminate the deduction for mortgage interest on vacation homes and the deductions for state and local taxes.

“I think almost all of the major tax expenditures could be trimmed, curtailed or eliminated,” said William G. Gale, co-director of the, Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center. “I don’t think any stand scrutiny with the possible exception of charitable contributions . . . But even there, if you said that’s got to change because the other ones are changing, I would not object.”

Camp and other Ways and Means committee Republicans and Democrats began preliminary conversations last week on how they might begin to whack away at the thicket of special tax provisions, including “tax-favored retirement accounts.” However, Camp cautioned that an “overwhelming majority of full-time workers rely on those provisions.”

Indeed, an analysis by the Hamilton Project shows that while eliminating the biggest tax deductions would yield substantial savings for the government, it would sharply cut into the after-tax income of families in almost every income bracket.

Rep. Sander Levin of Michigan, the ranking Democrat on Ways and Means, argued that by eliminating the deduction for state and local taxes, Congress could be putting many Americans in jeopardy of being double-taxed. Congressional leaders considered eliminating the deduction on state and local taxes as part of the 1986 tax reform, but backed down after lawmakers from New York and other high tax states protested.

Moreover, any attempt to tamper with the long cherished mortgage interest deduction would be certain to bring angry homeowners, the real estate and building industries, and financial institutions down on the heads of lawmakers. A survey commissioned by the National Association of Home Builders early this year showed that 75 percent of voters believe it is “appropriate and reasonable” for the federal government to provide tax incentives.

“Those running for office in November need to understand that voters will not look kindly on any candidates who seek to dismantle the nation’s long-term commitment to home ownership,” said Bob Nielsen, president of the National Association of Home Builders.

House GOP leaders would have to expect a similar backlash from corporate America, financial institutions, the insurance industry and consumer advocates if they attempt to eliminate other major tax breaks and deductions for employer provided health insurance, 401(k) savings and other popular provisions.

On Thursday, 27 Republican and Democratic House members lined up to testify before a Ways and Means subcommittee on behalf of scores of smaller tax credits and deductions – ranging from renewable energy and research credits to charitable contribution incentives to advantageous depreciation allowances for restaurants and retail outlets – that have either expired or are scheduled to expire this year.

Rep. Wally Herger Jr., R-Calif., a senior member of the Ways and Means Committee who spoke out on behalf of charitable deductions as part of estate planning, acknowledged that the House is facing a daunting task in choosing winners and losers among the raft of deductions, but insisted lawmakers have no choice but to do this.

“Not all of them will be eliminated, but probably many of them will,” Herger told The Fiscal Times. “But I think that in the big picture, we have to look at all of them together and set these priorities as a Congress. I agree that our highest priority has to be to bring our corporate rate down so that we can be competitive abroad, so that we can have incentives to begin hiring again and getting our economy going.”