Everyone knows why Willie Sutton robbed banks. That’s where the money was.

Maybe it’s time for jobseekers to borrow a page from old Willie when looking for work. No, not rob banks. They should go to where the jobs are.

Alas, the housing bust left millions of homeowners owing more on their mortgages than the homes are worth. That makes it difficult for people to sell and uproot themselves. Americans, a notoriously restless people over the course of their history, have become far less mobile in the wake of the Great Recession.

But if people who are down and out have the resources and gumption to get up and go, there are many metropolitan areas in the country that are adding jobs at a fairly encouraging pace. And, not surprisingly, the unemployment rate in most of these markets has fallen well below the national average.

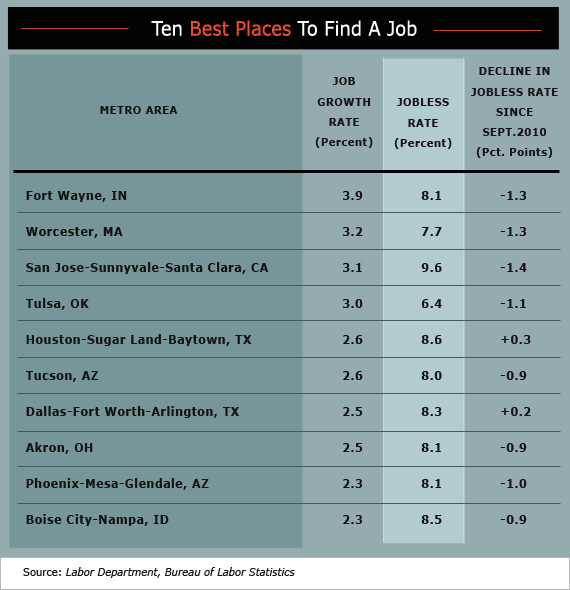

The Fiscal Times ranked the 100 largest metro areas in the U.S. by the rate of new job generation over the past 12 months, compared to the number of jobs they had in September 2010. The top ten included small cities and large cities, areas from the Northeast to the Southwest dominated by rustbelt and high-tech industries.

Two small cities – Fort Wayne, Ind., and Wooster, Mass. – topped the list. The others include Akron, Boise, Phoenix, Houston, Dallas, San Jose, Tucson and Tulsa. Not surprisingly, economic development officials in those areas were quick to brag about their communities and their sterling performances over the past year.

“We’ve got our act together,” Andi Udris, president of the Fort Wayne-Allen County Economic Development Alliance, told The Fiscal Times Thursday. “We’ve had a real coming together of the private sector and the public sector to get things done.”

While adding 8,000 jobs to its base of 203,000 jobs doesn’t sound like much by big city standards, Fort Wayne’s 3.9 percent increase in the total number of jobs placed the city at the top ranking. That surge was also enough to bring the unemployment rate down by 1.3 percentage points to 8.1 percent – a full point below the national average.

Federal fiscal policy – continued high levels of military spending and the auto bailout – were a major boon to the area. Local defense contractors like Raytheon and Northrop-Grumman are continuing to do well, and General Motors is investing $270 million in its local assembly plant, which will add 150 jobs to the company’s 3,300-person workforce. B.F. Goodrich is also expanding. “If we hadn’t had the bailout, it would have hurt Ft. Wayne,” Udris said.

Smaller companies are doing well, too. Vera Bradley, the handbag maker that two local women started in a garage 30 years ago had its IPO last year and is in the process of adding 250 jobs as it expands its local headquarters and distribution facility. Gains like those allowed the area to shrug off the loss of 800 jobs when Navistar moved its engineering facility to the Chicago suburbs.

The biggest challenge facing the community? Getting young, college educated youths to move to or return to Fort Wayne. “We’ve had a perception problem,” Udris said. “Young people don’t want to stay because they see this as a sleepy town. But it’s a wonderful place to live and executives say that when young families move here, they can’t get them to leave because it’s such a great place to raise kids.”

Wooster doesn’t have that problem. Just an hour west of the Boston metropolitan area with its education, cultural and sports attractions, Wooster is using that proximity to its best advantage. CSX is building a major regional freight rail hub; the University of Massachusetts Medical School is expanding its research facilities; the city is in the midst of a major brownfield redevelopment project that is attracting biotech and life science firms.

“I’ve been doing economic development in Wooster since the early 1990s, and I am seeing a lot of things starting to align here that is going to make us stable over the long run,” said David Forsberg, president of the Wooster Business Development Corp. “We don’t hit a lot of home runs and we don’t strike out a lot. We hit the singles and doubles that are allowing us to buck the Northeast trends.”

Technology is playing a major role in Phoenix’s comeback from one of the worst housing busts in the country. Even with housing prices continuing to fall as foreclosures rise, the metro area added nearly 40,000 jobs in the past year while lowering the unemployment rate to 8.1 percent. A year ago, economic prognosticators predicted the state wouldn’t get to 8 percent unemployment until 2013 or 2014 at the earliest.

The number one factor behind the boom is clean energy technologies, said Barry Broome, president of the Greater Phoenix Economic Council. The area has a number of leading U.S. solar panel manufacturers, including First Solar, and is busy wooing Chinese companies. One, Suntech, has already moved to the area and two more are on the way.

“We’re either going to have American renewable energy jobs or Chinese renewable energy jobs,” Broome said. “It’s either Ford or Toyota. It’s important for Washington to pay attention to the 2.4 million jobs in clean technology in the U.S., 100,000 of which are solar. It’s really important for the government to step through this Solyndra situation carefully.”

The region is also benefiting from a major investment by high-technology firms. Intel, the world’s leading microchip maker, is pouring $3.5 to $5 billion into a new manufacturing plant that will create 1,200 jobs in Chandler, which is next door to Phoenix.

The technology rebound also put the Silicon Valley metro area around San Jose on the top ten list. That area, like Phoenix, also suffered from the housing bust, and its unemployment rate remains stuck above the national average. But when housing comes back in these cities, “we’ll be booming,” Broome predicted.

The two largest metro areas in Texas – Houston and Dallas – also made the list. But unlike the other areas, their unemployment rates crept up in the past year even though they added a relatively large number of jobs. Those areas benefited from high oil prices, the growth in business services to the oil and gas industries, and, until recently, strong public sector job growth, which was fed by federal stimulus money, oil extraction revenues and relatively small housing price declines. The state passed strict mortgage regulations in the wake of the savings and loan collapse of the late 1980s and early 1990s, which kept the housing bubble at bay in Texas.

Pia Orrenius, a regional economist at the Federal Reserve Bank in Dallas, said the uptick in unemployment in the two large Texas cities -- which unlike the jobs numbers was based on a less precise household survey -- was due to people flocking there to find work in the state’s booming oil and gas industries, which benefited from high gas prices. “We got bigger inflows during the downturn because things weren’t as bad here,” she said.

But she warned the good times might be coming to an end. Not only have oil prices moderated, but “government jobs are falling here now, like the rest of the country,” she said. “A lot of teacher layoffs just went through.”