In mid-July, American Electric Power, one of the largest electric utilities in the U.S., cancelled plans to build its first-ever commercial-scale plant for capturing carbon dioxide emissions. The $700 million project – about half financed with a Department of Energy grant – would have taken at least 90 percent of CO2 emissions from coal-fired plants in New Haven, W.Va., and stored it in rock formations about one-and-a-half miles below ground.

As a state-regulated utility, AEP couldn’t increase its West Virginia electrical rates to cover its portion of the investment unless there were new federal regulations requiring the company to make the investment. Neither Congress nor the Environmental Protection Agency has taken action to force utilities to limit their carbon emissions.

“We fully assumed there would be federal climate legislation so we could go to the state to recover our half of the costs,” says Pat Hemlepp, a spokesman for AEP. “But because there were no rules in place, we had to cancel.”

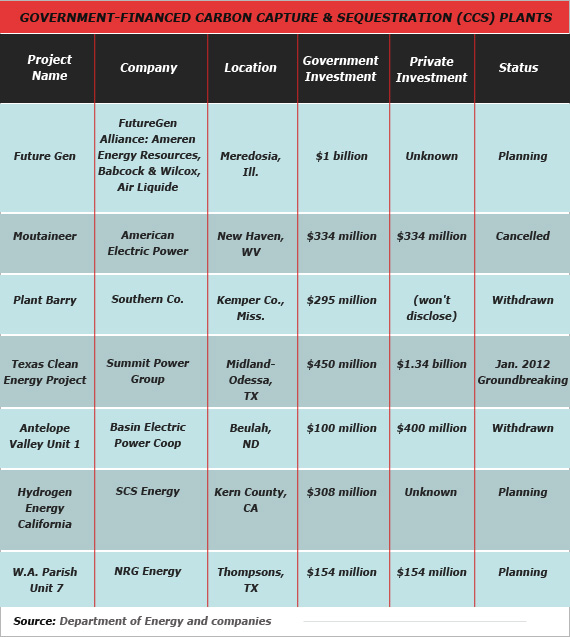

AEP is not alone. Major electric producers from the upper Midwest to the Deep South have cancelled carbon-capture projects in the past year even though they would have been half-financed with government grants. Meanwhile, the $1 billion government investment in FutureGen, an experimental plant resuscitated by the Obama administration and to explore next-generation carbon capture technology, is still on the drawing boards. The administration awarded the grant to a group of firms that promised to locate the facility in Obama’s home state of Illinois, which won out over a rival Texas bid.

The level of taxpayer cash poured into cancelled projects – aimed at developing cutting-edge technology and reducing greenhouse gas emissions -- is not trivial. AEP, for instance, used at least $22 million in government grant money to develop the plans, which have now been shelved. While that project financed with government stimulus funds created 67 jobs, according to company filings posted on a government website, cancellation of the facility, which was slated to come on line in 2015, ended hopes for 800 multi-year construction jobs and 30 permanent jobs.

In recent weeks, Republicans on Capitol Hill have focused public attention on the only failed project – Solyndra – among the 42 investments the federal government made in solar technologies. That loan-guarantee program was designed to resuscitate U.S. manufacturing in a field now dominated by Chinese and German producers.

However, ignored at the hearings and lost in the attendant media frenzy was the fact that the U.S. is on the cusp of losing out on another leading technology of the 21st century – capturing and either using or storing waste carbon dioxide that comes from burning coal, which is certain to remain a major fuel for generating electric power for at least the next half century. Coal still accounts for 45 percent of U.S. electricity production, while China’s exploding economy is building one coal-fired plant a week.

China is also investing heavily in carbon capture and store (CCS) technology. It recently opened its first CCS facility at a power plant near Shanghai.

CCS makes sense only in the context of efforts to curb global warming-causing greenhouse gases – primarily the CO2 that comes from burning fossil fuels – because there are just a handful of potential commercial uses for the gas.

One use is to pump the CO2 into depleted oil wells to bring to more oil to the surface. Or it can be used to make urea fertilizer. But most coal-fired generating plants aren’t near old oil wells, and there’s only limited global demand for new sources of fertilizer. So underground storage will be the outcome for most CO2 captured at power plants.

Therefore, widespread deployment of CCS requires putting a price on carbon, which the failed 2010 energy bill would have done through a “cap and trade” system. Many Republicans dubbed it “cap and tax” in opposing the bill. The Environmental Protection Agency could also issue emission rules that would force utilities to reduce their carbon emissions. An EPA inspector general’s report released Wednesday faulted the agency for failing to follow sound scientific procedures in declaring two years ago that CO2 poses a threat to human health, which would lay the groundwork for future regulation under the Clean Air Act.

Either route – creating a market for carbon capture or federal regulation – would allow utilities to go to their state utility commissions to recoup the investment in the form of higher electricity rates.

How high? Howard Herzog, a senior research engineer at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Energy Initiative, estimates the retail cost of electricity would rise by about 25 percent without direct government subsidy for construction of the CCS systems. “If you don’t have a policy to create markets, the financing of CCS projects becomes very difficult,” he says. “It’s more expensive [than uncontrolled coal burning], but it competes successfully with other low carbon technologies.”

In the hope that the then-Democratic Congress would enact an energy bill, the February 2009 stimulus act set aside $3.4 billion for clean coal technology programs. Included was an $800 million grant program to help defray up to half the cost of installing the latest CCS technologies in commercial-scale facilities; a $1.5 billion research program for developing more advanced system for capturing, storing and developing commercial uses for CO2; and the $1 billion for FutureGen.

The FutureGen project had been cancelled in 2008 by the Bush administration because its initial formulation used a technology that had already been demonstrated to be feasible at large plants. It has now been reconfigured to explore the technological viability of burning coal in a pure oxygen environment, so-called oxy-combustion, which would both lower the capital costs and increase the amount of carbon captured from the coal-burning process.

The entire DOE program is designed “to de-risk project technology,” says Jim Wood, deputy assistant secretary for clean coal at DOE. “The intent is by 2015 to have a range of technologies that will drive down the cost of capture so it will be only a 15 percent higher electricity bill, if and when there’s greenhouse gas regulation.”

But absent those regulations, the projects make little sense to traditional utilities. The Southern Co., which operates utilities in Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, and Louisiana, in January cancelled a major carbon-capture facility near Birmingham. The company refused to release details about its plans, which utilized technology developed by Mitsubishi Heavy Industries, but the government was planning to invest $295 million in the project. The company also declined to reveal how much federal money was spent on planning.

For the time being, the company plans to move forward using its own funds to build a much smaller pilot project at the site. “DOE is providing technical expertise and design support,” a spokesman for the company says.

The Basin Electric Power Cooperative in North Dakota had already lined up a $100 million DOE grant and a $300 million loan guarantee from the Agriculture Department to install a CCS facility at its Antelope Valley station, a project whose total could have reached $500 million. But after getting the grant, the company backed away. “The entire project was way too expensive, and it was only a demonstration project,” says Daryl Hill, a spokesman for the state-owned utility.

Some of the planning money spent by DOE may have been wasted. The DOE’s National Energy Technology Laboratory gave out a number of grants to study geologic formations around the country as potential sites for carbon storage. The North American Power Group (NAPG) in Greenwood Village, Colo., received $9.9 million to study the Powder River Basin in Wyoming, where it has been planning to build the Two Elk Energy Park to provide electricity throughout the region.

According to a report in the online publication WyoFile.com, written by former Los Angeles Times journalist turned Wyoming resident Rone Tempest, nearly $1 million of the stimulus act funds went to pay the salary of NAPG Chief Executive Officer Michael Ruffatto, whose campaign contributions dot the financial records of candidates from both political parties. Another $128,000 paid the salary of Brad Enzi, son of Sen. Mike Enzi, R-Wyo.

Llocal residents dismiss the NAPG project as “No Elk,” since it has been in the planning stages for more than a decade. The company’s most recent filings with the government said “no new direct jobs have been created by this project.”

CCS has divided the environmental community, with some activists questioning the technology from the start. “It does not make coal cleaner,” says David Graham-Caso, a spokesman for the Sierra Club. “There’s still a host of problems with burning coal, from the other toxic gases that go up the smokestack to the disposal of ash. We should be looking at clean energy solutions like solar.”

But numerous environmental groups such as the Union of Concerned Scientists and the Natural Resources Defense Council are strong backers of CCS technology. “Between now and 2035, fossil fuel use will increase by 50 percent around the world, mostly driven by growth in China and India,” says John Thompson, the CCS expert for the Clean Air Task Force, a coalition of environmental groups. “We can’t live with the consequences, so it really points to the need for widespread CCS.”

At least one government-supported project has figured out how to make the finances work in the current environment. The Summit Power Group, chaired by Donald Hodel, energy secretary in the Reagan administration, this week received final environmental clearance for breaking ground on a $2.4 billion, 400-megawatt plant (about half the size of a new nuclear plant) near Odessa, Tex. By using the latest technology, which takes pulverized coal and turns it into synthetic gas before combustion (so-called integrated gasification combined cycle, or IGCC, technology), the Texas Clean Energy Project plans to capture 90 percent of the CO2 produced at the new facility, which will supply electricity to San Antonio. Siemens and the Linde Group from Germany developed the technology..

While the government provided $450 million in grants and $313 million in tax credits for the project, it wasn’t enough to make the finances work. So the developers came up with a scheme to produce 720,000 tons of urea fertilizer, about a fifth of current domestic production;the U.S. imports about 5 million tons a year. The plant will also sell compressed CO2 to owners of depleted oil wells in the region.

“Our business plan never envisioned needing a carbon tax or cap and trade,” says Laura Miller, the former Democratic mayor of Dallas who now runs the project for Summit. A former journalist, she became prominent in local politics by opposing TXU Co.’s plans to build 18 traditional coal-fired plants throughout Texas.

“This is real expensive, a first-of-its-kind project,” she says. “But we think this is the right coal plant for the future.”