The Republican Party has produced as front-runners for the presidential nomination two men just three years apart in age but who otherwise are about as different as possible — in style, substance, biography and their appeals to voters.

One was born into a privileged family in a tony Michigan suburb; the other, onto a flat expanse of West Texas dirt with no indoor plumbing. One spent his youth tooling around his father’s car factory; the other, selling Bibles door to door so he could afford to buy a car. One excelled at Harvard University, simultaneously earning law and business degrees and swiftly climbing the corporate ladder; the other, his hope of becoming a veterinarian dashed when he flunked organic chemistry at Texas A&M University, joined the Air Force.

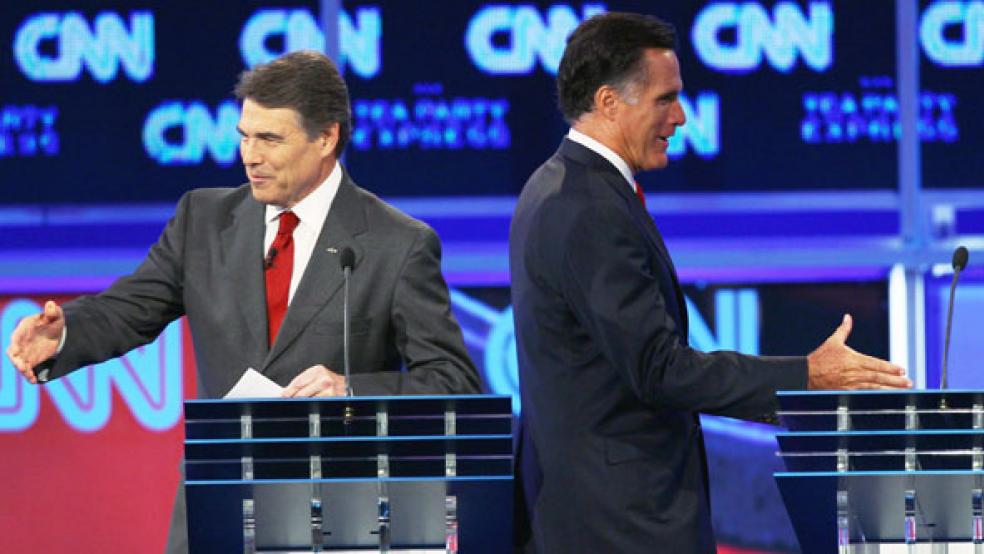

Where Mitt Romney is obedient and cautious, Rick Perry is bombastic and spontaneous. If they had attended the same high school, they probably would have hung out at opposite ends of the hallway. Their relationship today is said to be frosty, if there is one at all.

“In every single possible way, they come from different worlds,” said Republican strategist Alex Castellanos, who advised Romney in his 2008 race but is unaffiliated in the 2012 race. “You can see the playbook pretty clearly here: It’s populist against patrician, it’s rural Texas steel against unflappable Romney coolness, conservative versus center-right establishment, Texas strength versus Romney’s imperturbability, Perry’s simplicity versus Romney’s flexibility.”

In making their pitch to Republican voters, Romney and Perry both say their life experiences have prepared them for the presidency and for the onerous task of nursing the country’s ailing economy. Romney is campaigning as a steady, capable grown-up who can fix anything that needs fixing; Perry, as a passionate, principled leader who can channel the ire of a frustrated electorate.

The twin forces within the Republican Party are neatly manifested in the two candidates. Romney represents both the party’s upper-crust establishment and the state — Massachusetts — that for so long has been the GOP’s boogeyman. Perry represents the angry grass roots that are giving the party new energy and he personifies the state — Texas — that for a generation has been the GOP’s soul.

Just as Obama’s 2008 victory over Hillary Rodham Clinton helped define the modern Democratic Party, Republicans, in choosing between Romney, Perry or perhaps someone else, will make a powerful statement about the GOP’s identity.

Relating to Voters

Romney, a former consultant who founded a successful private-equity firm, seems at his best discussing the intricacies of how businesses grow. When he announced his 59-point economic plan, Romney began by saying that “this is going to be a conversation” and proceeded to speak extemporaneously for half an hour with just one page of hand-scribbled notes.

It’s when Romney tries to relate to average folks or banter about trivial things that he can struggle. His critics poked fun at snapshots he posted to his Twitter account showing him aboard Southwest Airlines and eating a Subway sandwich. When Romney posed for a picture with the staff of a ’50s-themed diner in New Hampshire over the summer, he pretended one of the waitresses had pinched his backside. His attempt at a practical joke left those around him puzzled.

Perry tends toward just the opposite. When he gave a short speech on jobs in California recently, he was so focused on reading from the notecards he carried to the podium with him that he didn’t seem to notice that a woman in the bleachers had passed out under the hot sun or that people were shouting for paramedics.

It’s in relating to people that Perry seems most at ease. He routinely puts down elites. In last week’s debate, Romney dismissed Perry’s jobs record as luck, saying that governing a state with plentiful oil resources was akin to being dealt a poker hand of four aces. Perry shot back on the stump in Iowa:

“I grew up in a house that didn’t have running water until I was about 5 years old. My mom and dad were both tenant farmers. For sure, I was not born with four aces in my hand.”

Perry does little to hide his disdain for Romney’s state.

“I would no more consider living in Massachusetts than I suspect a great number of folks from Massachusetts would like to live in Texas,” Perry wrote in “Fed Up!” “We just don’t agree on a number of things. They passed state-run health care, they have sanctioned gay marriage, and they elected Ted Kennedy, John Kerry, and Barney Frank repeatedly — even after actually knowing about them and what they believe!

“Texans, on the other hand, elect folks like me. You know the type, the kind of guy who goes jogging in the morning, packing a Ruger .380 with laser sights and loaded with hollow-point bullets, and shoots a coyote that is threatening his daughter’s dog.”

Romney and Perry’s uneasy relationship dates to 2006, when Romney, then the Republican Governors Association chairman, hired Castellanos to work for the RGA. Perry viewed that as an affront, since Castellanos was also working for Carole Keeton Strayhorn, an independent who was trying to unseat Perry that year.

The next year, Perry endorsed Rudolph W. Giuliani over Romney in the presidential race. In his 2008 book about the Boy Scouts, Perry accused Romney of excluding the Scouts from volunteering at the 2002 Winter Olympics, which Romney ran.

Republicans close to Romney and Perry said that reports of their animosity are overstated and that in reality they never had much of a relationship at all. Romney supported Perry’s reelection campaign last year and, when he visited Texas this spring, before Perry was openly considering a presidential run, lavished praise on the Texas governor.

Defining Influences

On the campaign trail now, both men tell inspirational stories about their fathers. One is a tale of ambition and achievement; the other, of honor and minimalism.

The story Perry tells of his father, Joseph Ray, is markedly different. “My dad was a tail-

gunner in World War II,” Perry recently told a veterans group. “He flew 35 missions over Nazi hell Germany in 1944 and ’45. He helped liberate millions from tyranny. When he came home, he didn’t seek acclaim or credit. He just wanted to live in peace and freedom — just farm a little corner of land in Paint Creek, Texas.”

That corner of land is where the mischief-making, eager-to-please “Little Ricky” was raised. Growing up, Perry says, the only world he knew was Paint Creek. “I learned the values of hard work and thrift and faith,” he said Friday in Iowa. “The American dream was available to me because America was never set up as a class society.”

At a piano recital when he was 8, Perry met Anita Thigpen, who, 24 years later, would become his wife. When he got to Texas A&M, Perry joined the Corps of Cadets and was elected as one of A&M’s five yell leaders. Perry said he learned there was more to college than fraternity parties — “Quite frankly, I struggled,” he said recently — and graduated with a degree in animal science. To this day, he kneels down to pet dogs when he sees them.

Perry joined the Air Force, piloting transport aircraft from 1972 to 1977, although he was never called into battle.

Perry has said that at age 27, when he returned to Paint Creek to work the family’s cotton farm, he was “lost, spiritually and emotionally.” He pondered his purpose but found God. And, in 1984, he launched what would become a nearly three-decade political career. He won 10 straight elections — state representative, agriculture commissioner, lieutenant governor and, when George W. Bush became president, governor.

“It’s a whole package,” David Carney, Perry’s chief strategist, said in a recent interview. “This is not manufactured. That’s what makes Rick Perry who Rick Perry is.”

Romney doesn’t talk about flying cargo planes — he didn’t serve in the military — or going from rags to riches. He’s always had the latter. The places he has lived — Bloomfield Hills, Mich.; Belmont, Mass.; Park City, Utah; La Jolla, Calif.; and Wolfeboro, N.H. — have almost nothing in common with Paint Creek.

The biography Romney shares with voters is one of bullet points on what by any measure is an impressive résumé:

Learned French during two years in France as a Mormon missionary. Married his high school sweetheart, Ann, at age 22. Graduated from Brigham Young University and gave a commencement address to his class. Completed law and business degrees in four years at Harvard.

Became a rising star in the management consulting world. Founded Bain Capital. Helped invest in or acquire companies such as Staples, the office-supplies retailer. Turned around the struggling 2002 Winter Olympic Games. Was elected governor of Massachusetts. Ran for president.

“I don’t have all the answers to all the problems that exist in America and around the world,” Romney has said. “But I know how to find the answers, and I also know how to lead.”

It is perhaps in the area of personal style that the two men are most different.

Consider how they approached the rite of eating a corn dog when they visited the Iowa State Fair last month. When a fair vendor handed Romney a vegetarian corn dog, he politely took it, turned his back to the cameras following him, took a delicate bite from the side and hurried along so he wouldn’t be photographed sticking the deep-fried foot-long in his mouth.

Perry, meanwhile, took a big bite of his corn dog, top first, photographic evidence of which raced around the Internet.

“A guy gave me a corny dog and it looked beautiful,” Perry recalled a few days later in South Carolina. “I took a big ol’ bite out of it and I thought, it kind of has an odd taste. He said, ‘It’s a vegetarian one. How do you like it, sir?’ ”

Stirring his audience of apparent meat lovers, Perry continued his riff.

“Let’s see,” he said, “I think [I ate] boiled egg on a stick and finished up with pork chop on a stick. So I got my protein that day!”

Romney’s father, George, was born to American parents in Mexico but grew up poor, hopscotching the American West, and eventually learned to be a lath-and-plaster carpenter.

“My dad never had the time or money to put together a college degree, but the fact that he was a lath-and-plaster carpenter didn’t keep him in America from becoming head of a big car company — they made Ramblers — and then also becoming governor,” Romney said recently at a New Hampshire town hall meeting, not mentioning that his father never realized his ultimate ambition, to be president.