In the midst of one of the worst job markets since the Great Depression, Americans may forego new cars and skip fancy restaurant meals. But they’ll do almost anything to avoid scrimping on their kids. A middle-income family ($57,600 to $99,730 in household earnings) will spend $286,860 raising a child over 17 years—a figure that continued to tick up even during the recession. More affluent parents, those earning $100,000 or more, spend $477,100, or nearly twice as much, according to the Department of Agriculture. And that doesn’t include college.

While consumer spending on everything from autos to ovens has dropped over the past 10 years, Americans continue to open their wallets for their kids. Overall, parents spend 66 percent more on childrearing than they did 10 years ago, according to Pamela Paul, author of Parenting, Inc., thanks largely to rising child-care and education costs. But parents are spending more across the board. Last year, the market for children’s goods, which includes everything from stuffed bears to changing tables, increased by 5 percent in 2010, to $18 billion, according to market research Packaged Facts.

Are parents getting their money’s worth? The desire to give one’s child every advantage is deeply ingrained in the American psyche. And as our confidence that our children will have a higher standard of living than we do has dropped, investing in our kids seems more important than ever. For affluent parents, full-time nannies, $600 gymnastics programs, $1,500 strollers or $30,000-a-year preschools can seem like part of the deal.

Some of these purchases undoubtedly are more about parental status than a desire to turn toddlers into achievers. But many well-meaning families grapple with personal parenting choices that have big economic consequences: nanny vs. daycare, public school vs. private, enrichment courses vs. free time. And while solid research on these subjects is often inconclusive, there’s very little evidence that the best childhood money can buy is worth the expense.

Giving Kids "The Best"

Kerry Gillick Goldberg and her husband, Joe, work hard to give their six-year-old daughter every edge: $5,000 a year for preschool, $144 a month for swim lessons, $1,200 a year for gymnastics and dance, $6,500 for summer camp, not to mention $30,000 a year for the nanny so Goldberg can go to work and make enough to pay for everything. Even though the Goldbergs bring a combined $200,000 a year, they feel strapped. “We made a decision to have no money for X number of years to make sure my daughter had the best,” she says.

Yet much of what kids need to thrive doesn’t require hefty expenditures, according to child development experts. “Parents are throwing resources at their kids and getting caught up in ‘everybody else is doing it,’” says Po Bronson, author of NurtureShock: New Thinking About Children. “We’re not talking about rich parents, we’re talking about regular people who otherwise wouldn’t be spending this kind of money on themselves and didn’t spend this kind of money before they had kids, and now they’re milking their bank accounts and saving nothing to do all these things for their kids.”

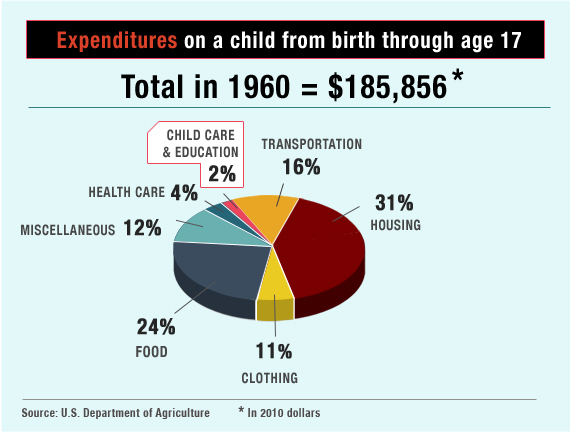

The share of family budgets devoted to child care and education has gone from 2 percent to 17 percent in the past 50 years, though much of this increase is due to women flooding the workforce.

Simply teaching kids the importance of hard work trumps even innate intelligence in predicting their success, according to Carol S. Dweck, a psychology professor at Stanford and author of The Secrets to Raising Smart Children. Children who live in homes filled with books, regardless of the parents’ educational background or occupation, do much better in school, according to a 2010 study by researchers from the University of Nevada. “You can get a lot of bang for your book,” said author Mariah Evans, a sociologist. “It’s quite a good return on investment in a time of scarce resources.”

Neil Gussman from Lancaster, PA, and his wife, Annalisa Crannell, are trying hard to resist parenting peer pressure. They recently started a blog called Miser Mom, and pride themselves on being frugal with their kids. With a combined income of more than $160,000, they could afford to send their two boys, 11 and 12, to private school in Lancaster, PA, where they live. But the boys go to public school and their clothes and toys come mostly from yard sales. Rather than spending money on preschool, Gussman says he reads to them every night instead. He believes that’s enough. “Many parents want their child to achieve everything they possibly can and they don’t want to feel guilty so they give them all kinds of stuff,” he says. “We’re sprinting in the opposite direction.”

Every family faces different challenges, of course, and some parents do not have good low-cost options, especially in urban areas. There may also be intangible benefits to a private-school education, such as making connections and learning social values. But while some steep parenting expenses pay off, there is evidence of diminishing returns: Overall kids from higher socioeconomic backgrounds tend to do better in terms of test scores, college admissions and economic advancement, according Bronson. But at some point additional spending makes no additional affect. For example, there’s little evidence that very wealthy children generally do better than upper-middle class kids.

Here is our own break down of big parenting costs, along with a survey of existing research and an analysis of whether they’re worth the extra dough.

Child Care

Stay-at-home parent, day care center or nanny? Every family grapples with this decision and only one thing is certain: each one has a price. Staying home costs one partner’s salary, not to mention the number of uncompensated “overtime” hours moms put in. Day care ranges anywhere from $350 a month in small towns, to more than $1,000 per month in urban areas per child. For a newborn in New York City, the average family spends up to $16,250 per year on child care, and elite preschools with long waiting lists are popping up everywhere. One Manhattan preschool costs $37,825 a year.

Despite the debate that rages on mommy blogs, there’s very little rigorous research into the payoff for the more expensive options and none of it is conclusive. “A good nanny, a good parent, and a good day care can all be very effective,” says Bronson. Assuming ‘the more expensive, the better experience’ is not always the case, as a bad day care or nanny experience can harm a child’s development.

Educational Products for Infants

Before parents even have the option of sending their child to school, many pour money into early education software and merchandise like Baby Einstein (a set of 12 DVDs costs $179.99), Brainy Baby (entire learning collection is $199.92), baby sign language classes ($49.95 for a DVD kit, or about $150 a class). One company selling early education DVDs and videos for $12.99 each, Baby Prodigy, grossed over $250,000 in the first four months when it launched in 2003.

At Kumon enrichment centers, which originated in Japan, parents pay $200 to $300 a month for two hours a week of tutoring in reading and math. They enroll toddlers as young as 2, and now have some 250,000 students nationwide.

According to the 2007 report, Million Dollar Babies: Why Infants Can’t be Hardwired for Success, the educational baby merchandise industry has gone from nonexistent 50 years ago, to a multi-billion dollar business. But there’s little evidence that any of it makes a difference. One study by the University of Washington even found that infants who watched Baby Einstein DVDs understood fewer words than infants who didn’t. “The companies have tapped into parental angst over doing enough for their kids,” writes author Sara Mead, but “there is no hard evidence that their products will make tots smarter.”

Private vs. Public school

A common dilemma for the growing number of urban parents (90 percent of the population is expected to live in cities or suburbs by 2050), is to pay more, a lot more, for private school, or take a chance on public schools. In many cities, lottery systems can land kids in less-than-desirable districts, and spending more on a private school might be a worthy option that pays off in the long run.

But within cities and suburbs, there are excellent public schools that in some cases meet or exceed the scores of the nation's best private prep schools. In New York City, for instance, Stuyvesant High School is considered one of the most elite institutions in the country, with a first-rate faculty, outstanding lab facilities and students who graduate with scholarships to MIT, Stanford and other prestigious universities.

Summer Camp

Long gone are the summer camps filled with roasting marshmallows and campfire sing-alongs. Specialized camps have grown exponentially in the last decade. There camps at MIT devoted to teaching kids how to build iPhone apps ($3,299 for two weeks), video game development camps ($3,299 for two weeks), NASA space camp ($699 to $899 for six days), robocamp ($650 to $859 for 10 days), a sailing and scuba-diving camp in the Caribbean ($4,550 for three weeks, plus air fare). Other YMCA day camps run cheaper, but still cost about $150 to $400 per child per week.

This one might be worth it, depending on the activities: “By and large, going to camp and being active is good for your kids compared to staying home and being on the couch,” says Bronson. “You can go build a fort with the couch and have a wonderful, enriching time with your kids, and that’s great for development, let alone being good for the relationship, if you’ve got the time. But in lieu of time, a lot of people spend money.”

Other Enrichment Classes

Piano lessons, gymnastics, karate, after-school tutoring, foreign language classes. It all adds up. According to Bronson, there are some studies that show music helps with math development, but, he adds: “not as much as going to math class.” He says that many activities that cost parents nothing help with child development, including exercise, art, reading to a child, or playing with legos. “Parents feel a competitive instinct that they’re depriving their kids because they’re not doing as much as other families,” he says, “but it’s about learning to resist that urge and say, no, my child has a great life.”