Scores of ideas for reducing the deficit will be put on the table at an all-day fiscal summit on Wednesday. But bringing the deficit under control and putting the nation on the path toward fiscal probity is challenging, frustrating work. In the end, it will all boil down to resolving a debate over the size and scope of government, according to a broad range of deficit reduction plans.

The speakers' roster, headlined by former President Bill Clinton, the last chief executive to preside over a balanced budget, will address the need for a long-term plan to bring the $1.4 trillion annual budget deficit under control. But the centerpiece of the conference will be the unveiling of six plans from across the ideological spectrum, each financed by the Peter G. Peterson Foundation, the sponsor of the annual event. Peterson, a former Wall Street financier and Commerce Secretary, also funds The Fiscal Times. The plans were developed by (from ideological left to right): the Roosevelt Institute Campus Network; the Economic Policy Institute (EPI); the Center for American Progress; the Bipartisan Policy Center; the American Enterprise Institute (AEI) and the Heritage Foundation.

The proposals are all comprehensive and far ranging, and offer road maps to containing or stabilizing the deficit in the coming decade -- if not actually balancing the budget. Yet despite their ideological diversity, none of the plans contains a magic bullet that would readily solve the long-term problem. Moreover, most of the ideas have already made their way into the public arena or been thoroughly vetted in some previous think-tank report.

The report of the National Commission on Fiscal Responsibility and Reform issued last fall, outlined scores of recommendations for reducing deficits by $4.1 trillion over the coming decade. At least, it sparked an important national debate about the government’s unsustainable spending path. And the fierce clashes between the Obama administration and Republicans on Capitol Hill over long-term spending and tax policy, and raising the debt ceiling, underscores that the deeply rooted philosophical differences will be hard to bridge.

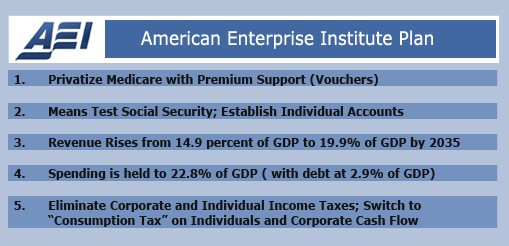

A simple comparison of the AEI and EPI proposals, what one might call the responsible right-of-center and left-of-center poles of the debate, reveals the width of the gulf. AEI would privatize Medicare and turn it into a premium support or voucher program, no different than what has been proposed by Rep. Paul Ryan, R-Wis. That plan, part of a budget recently approved by the GOP-controlled House, has drawn fierce opposition from liberal groups, and may receive an electoral rebuke in upstate New York later today.

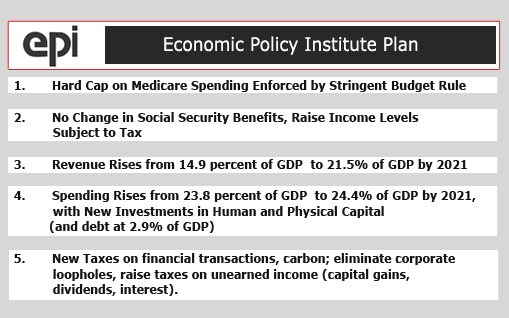

The EPI plan would increase range of taxes: on the well-to-do, on carbon, and on financial transactions to maintain entitlements and shore up investment in human and physical capital. Opposition to any form of tax increase has been the touchstone for any plan for balancing the budget in the eyes of most conservatives.

There is only one thing that both sides can agree on. “These choices are difficult,” said Alan Viard, a former Federal Reserve economist who is now at AEI. “When you actually stop and look at the numbers, it reinforces how difficult this is going to be.”

To put the two plans in perspective, it’s worth looking at what doing nothing entails. Call it the Congressional Budget Office plan, since their bean counter analysis always assumes current law will continue in place for the foreseeable future, defined as the next ten years.

Under the most recent budget and economic outlook, released by CBO in January, the nation’s total debt, currently $14.3 trillion, is slated to rise by nearly $7 trillion by 2021. Revenues a decade from now will equal 19.9 percent of the gross domestic product, while outlays for all purposes – including entitlements – will equal 23.5 percent.

That’s a deficit of about 3.6 percent of GDP, or slightly higher than what economists call primary balance since at that point the increase in debt each year will be about equal to the increase in economic growth. That’s the economic definition of affordable – when your debt doesn’t grow any faster than your income.

But look at what “doing nothing” assumes. It assumes that all the Bush-era tax cuts are allowed to expire – for the middle class as well as for the rich. It assumes there is no fix for the millions of families that will be swept up in the alternative minimum tax, which Congress adjusts every year. And it assumes there will be no pay increases for physicians who treat Medicare patients – something Congress until now has not been willing to allow, despite the adverse impact on the deficit.

On the spending side, a stand-pat approach assumes accomplishment of nearly a half trillion dollars in Medicare savings, which were included in the Obama administration’s health care reform legislation that skeptics call implausible. Republicans in Congress have vowed to repeal the bill. It assumes a freeze in domestic discretionary spending, which President Obama included in his budget proposal. And it assumes that war spending for Iraq and Afghanistan will remain about the same as it is now -- $159 billion a year – only adjusted upward for inflation over the next ten years. That’s another $1.8 trillion in spending that so far both parties in Congress and the Pentagon seem intent on funneling into other military projects.

In other words, doing nothing but drawing down troops abroad resolves the nation’s deficit problem – at least as defined by most economists. Of course, doing nothing isn’t an option since it requires military cuts and significant tax increases – by allowing the Bush tax cuts to expire. In other words, current law solves the deficit problem about the way that liberals in Congress would. For instance, it’s roughly comparable to the plan authored by Rep. Jan Schakowsky, D-Ill., who served on the national deficit commission, with the exception that she’d preserve the tax cut for the middle class.

Other deficit reduction plans can be measured against that benchmark. The December report from the president’s deficit commission, chaired by Democrat Erskine Bowles and former Republican Senator Alan Simpson, identified $4.1 trillion in deficit reduction between 2012 and 2020 compared to the CBO 2010 baseline. Their ratio of spending cuts to tax increases was about two-to-one.

But the report assumed spending that included the “doc fix” to block reductions in payments to doctors who treat Medicare patients, an extension of the middle class tax cuts, an AMT patch and a gradual reduction in troop commitments abroad. Even with its $4 trillion in cuts, it added $8.3 trillion to the national debt over the next decade before reaching primary balance.

President Obama’s budget proposal in February wasn’t much different than Bowles-Simpson, albeit adding $8.4 trillion of new debt via a different route. That included more spending and higher taxes on corporations.

The plan passed by the Republican-controlled House is the most extreme proposal in the political arena. The GOP plan would cut spending by $3.6 billion more than would Bowles-Simpson over the next ten years, through 2020, and $4.4 trillion more than Obama has proposed, through 2021. It would accomplish these huge savings by slashing aid to the states for Medicaid and cutting domestic discretionary spending. In fact, the Republican plan cuts so much in these areas that it makes room for another $1.8 trillion in tax cuts over the decade.

The EPI and AEI plans use similar benchmarks. The “conservative” AEI plan would still raise revenue to 19.9 percent of GDP and spending to 22.8 percent of the overall economy, not much different than CBO’s “doing nothing.” But to get there, it would turn Medicare into a voucher program; reduce Social Security to flat payments pegged to keeping seniors out of poverty while creating pre-funded individual retirement accounts financed by an employer-matched payroll deduction; and eliminate all income taxes in favor of a new consumption tax on individuals and a cash flow tax on businesses. The group would also maintain defense spending at about 4 percent of GDP, up from 3 percent assumed in the CBO baseline projection.

The AEI plan is a prescription for massive shifts in tax burden with millions of winners and losers. “We deliberately set ourselves the task of developing what is good policy, not what’s politically feasible,” Viard said. “Those steps always turn out to be so limited.”

EPI, on the other hand, would cut $5 trillion from current CBO assumptions, but would leave spending almost the same. “Our allocation is very different,” said John Irons, chief of research and policy at the liberal think tank. “We allocate a lot more money for investments, and lower defense spending.”

To finance that investment, they would target very specific groups for higher taxes: financial institutions; people with unearned income (capital gains and dividends); carbon polluters; and tax incentives aimed at specific industrial groups. They would also cap deductions like the mortgage interest write-off and the health care exclusion in a way that would preserve them for low- and moderate-income people but means test them for the well-to-do.

“Some people call it politically unrealistic,” Irons said. “But raising taxes on wealthier people and limiting defense spending is more popular than Medicare cuts or Social Security cuts.”