Many Americans think of the IRS as haggling with individuals over home-office deductions or piddling expenses. But consider telecommunications entrepreneur Walter Anderson hiding $365 million in off-shore accounts or Girls Gone Wild creator Joe Francis filing false corporate returns and defrauding the government out of $20 million. Somebody has to stop them.

For nearly three decades, Al Drucker was “the enforcer.” Drucker, 54, lives in Manalapan, N.J., has a thick New York accent and a gray speckled mustache. He was involved in the arrests of big-time tax crooks, helping to recover millions of dollars for the government. And he thinks the country deserves better. “The IRS is not respected as much as the employees would like, and that’s just the dynamic of our country. I wasn’t ashamed of telling people where I worked, but I wouldn’t necessarily volunteer the information,” he says.

Drucker was part of the Criminal Investigation department for 24 years, one of the smaller branches of the IRS with about 3,500 employees. His cases mostly involved businesses that tried to conceal income, but he also dealt with high-profile political tax scandals, and large-scale money-laundering and embezzlement operations, often working closely with the FBI, Department of Homeland Security and the Drug Enforcement Administration.

The IRS says some $350 billion in revenue is lost every year due to tax fraud and errors and closing the “tax gap” has become a priority. Last year, the IRS took in $57.6 billion from their enforcement efforts, up 18 percent from 2009. Obama’s still unapproved 2012 budget calls for an additional 5,100 agents next year and an increase of $460 million for tax enforcement (the GOP is proposing no additional funding.) Drucker estimates about one third of the IRS’s 106,000 employees are devoted to auditing and investigating tax cheats.

Born and raised near Queens, N.Y., Drucker went to John Jay College of Criminal Justice in Manhattan to study chemistry, thinking he would go into forensics. He’d always been interested in fighting crime, and took a government test hoping to find a job in the secret service or the Drug Enforcement Administration. Next thing he knew, the IRS called him in for an interview.

Allegations usually come from the three ex’s: the ex-spouse, the ex-employee, the ex-anyone. The ex’s are always the ones that kill you.

“The IRS was the last place I wanted to contact me,” he says. But at 26, he joined up as a general tax collector, the “front line of the IRS,” making $17,000 a year. After four years of knocking on people’s doors to try and get them to pay their tax bills, he applied to the Criminal Investigations department. During six months at the Federal Law Enforcement Training Center in Brunswick, Georgia, he learned how to make an arrest and conduct surveillance. He spend months dissecting tax forms and studying intricate tax law (though he says he now uses TurboTax to do his own taxes. “It’s easy,” he shrugs.)

As a special agent, he dealt with hundreds of cases, many initiated by suspicious audits. He’d also peruse the newspapers for cases, zoning in on people whose incomes didn’t match their extravagant lifestyles. “You can pick up The New York Times and read a great expose on John Smith and John Smith is posing in front of his airplane, now you’re thinking, ‘boy, I wonder what’s going on,’ and you can check the veracity of the story against known tax records,” he explains. Other cases came from whistleblowers: “Allegations usually come from the three ex’s: the ex-spouse, the ex-employee, the ex-anyone. The ex’s are always the ones that kill you.”

After two years in his new job, he was assigned to a $300 million money-laundering case involving a Columbian drug cartel. His team conducted surveillance of the suspects for nearly a year before issuing a warrant. Wearing his IRS raid jacket, bullet-proof vest and armed with a revolver, he and his team swarmed the premises. They arrested 12 people, and discovered 600 pounds of cocaine and $838,000 in cash. Drucker had his picture in the New York Daily News and New York Post.

In his retirement, Drucker and his wife run a window blinds shop. He also runs a website called Taxsqueal.com, where citizens can expose alleged tax evaders anonymously. He launched it last June and now spends about two hours a day channeling the allegations to the IRS. “Let TaxSqueal be your rat,” the website says. Drucker says he’s had a lot of traffic in the past few weeks thanks to tax season.

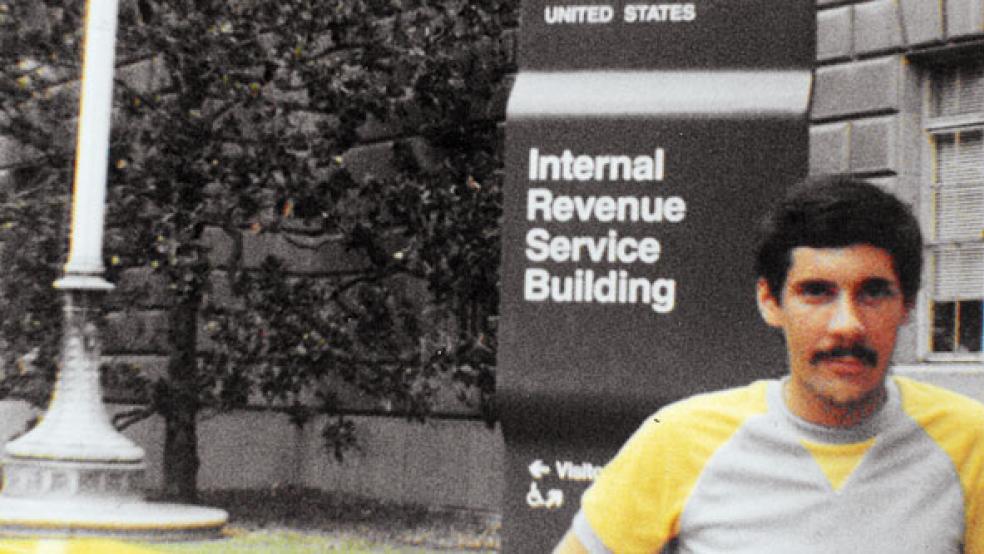

Drucker keeps a scrapbook of his time at the IRS, with a photo of him as a young man in front of the national IRS office in Washington, D.C., and newspaper clippings of his cases. His old badge and ID sit in a framed case. “Are there people that come in [to the IRS], do their eight hours and go home?” he asks. “Sure. But I was proud of my work. The finances are what make the country go round.”

Click to read all of The Fiscal Times’ Tax Day Countdown.