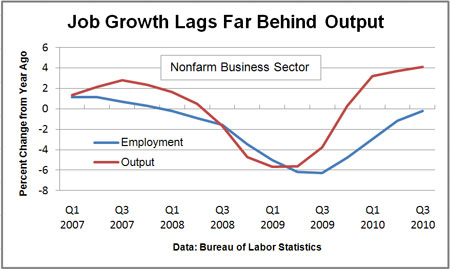

• Less economic uncertainty could mean more than 200,000 new jobs per month. • Nonfarm output is up 4.1 percent from a year ago. Payrolls are down. 0.2 percent. • Nonfinancial companies hold nearly $1 trillion in cash and short-term investments. |

These days businesses are certain of one thing: There's too much uncertainty. The most daunting unknown remains the direction of the economy, which sits atop a long list of other questions about tax policy, global finance, new regulations, and healthcare reform.

Republican inroads during the midterm elections and the Federal Reserve's latest plan to buy $600 billion in Treasury notes offer a bit of daylight on the direction of policy. Corporate America, especially Wall Street, seems somewhat relieved. However, uncertainty continues to stymie business expansion and hiring, and any hope for a stronger economy in 2011 will require that companies have a clearer vision of the future.

The news on job growth continued to improve in October, but cautious companies are still not adding workers at a pace that will make a dent in the unemployment rate, which held at 9.6 percent, same as in August and September. The Labor Dept. said Friday that businesses and governments added 151,000 workers to their payrolls last month, and job gains in August and September turned out to be greater than first reported. Over the past four months, private-sector companies have added 131,000 jobs per month, on average. However, while that's the strongest four-month gain since before the recession, with nearly 15 million workers still unemployed, it's only barely the pace needed to keep the jobless rate from rising further.

Economists will tell you that uncertainty is very different from risk, which businesses face every day. Companies identify risks, assign probabilities, and make decisions. Uncertainty involves risks that are either unknown or incalculable, and it can cripple an economy. Former Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan said it best after the financial shocks of the late-1990s: "The failure to be able to comprehend external events almost invariably induces fear and, hence, disengagement from an activity, whether it be entering a dark room or taking positions in markets." For a company right now, a step forward into the darkness by, say, adding new workers could end up costing a lot more than doing nothing at all.

Businesses clearly have the resources to expand their operations and payrolls at a faster clip. Outside the finance sector, U.S. companies held $943 billion in cash and short-term investments at mid-year, according to an analysis by Moody's Investor Services, up from $775 billion at the end of 2008. That's enough to more than cover all capital spending and dividends, a historically healthy standing. "We believe companies are looking for greater certainty about the economy and signs of a permanent increase in sales before they let go of their cash hoards," says Moody's Steve Oman in his report.

Given a cash-rich corporate sector, the impact of reduced uncertainty on future expansion and hiring could be significant. Economists at Barclays Capital have estimated the impact of uncertainty on job growth, using the Chicago Board Options Exchange's Volatility Index, better known as the VIX. The VIX attempts to capture expected swings in stock prices and is, thus, a key measure of uncertainty among investors. The higher the VIX, the greater the uncertainty. Barclays economist Troy Davig concludes that a drop in the VIX to its pre-crisis level, combined with only moderate economic growth, could push monthly job gains in the private sector to more than 200,000 by the end of 2011, compared to only 111,000 per month so far this year. That pace would make a significant dent in the unemployment rate.

Many companies are putting their cash to work, but amid so much uncertainty their first goal has been to enhance productivity and maintain profitability rather than expand the size of their operations. Over the past year, output among nonfarm businesses has increased 4.1 percent, but payrolls are still down 0.2 percent. It's true that business investment in equipment and software has been a growth leader in this recovery. However, outlays for computers and other labor-saving high-tech equipment now stand more than 16 percent above their level when the recession began almost three years ago, while investment in industrial machinery, transportation equipment, and other more labor-intensive categories, remains some 27 percent below its pre-recession peak.

The emphasis on productivity and cost control is evident in this year's corporate profits, which have consistently beat market expectations despite sluggish economic growth. In each quarter this year, 74 percent or more of companies in the Standard & Poor's 500 stock index have exceeded their earnings expectations, well above the 62 percent norm. JPMorgan Chase economist Robert Mellman notes that profit margins this year are approaching the high levels seen during the tech-fueled boom of the late 1990s.

How is that possible, especially with pricing power so weak? The answer is in the Labor Dept.'s latest report on productivity. Measured as output per hour worked, productivity among nonfarm businesses in the third quarter rose a greater-than-expected 1.9 percent from the previous quarter, and has grown 2.5 percent from a year ago. At the same time, hourly wages and benefits have increased only 0.5 percent. That means, adjusted for higher productivity, the labor cost of making each unit of output has fallen about 2 percent over the past year. Even with prices increasing a meager 1.2 percent, businesses have been able to maintain a high profit margin on the items they make and sell.

In a way, by keeping a keen eye on productivity, labor costs, and their bottom lines, companies themselves are feeding much of the uncertainty that clouds the outlook. "The high unemployment rate will remain a persistent risk to the outlook, creating lingering uncertainty about the recovery in the housing market, the sustainability of consumer spending, and the ability of the government at all levels to bolster activity," economists at UBS said in their latest research note. Improving economic data and a better handle on policy will go a long way toward lifting the shroud covering the future, but until businesses gain a lot more visibility their wait-and-see caution will continue to hold back the recovery.