Notwithstanding a career spent sifting through the wreckage of personal bankruptcies, and her family’s hardship after her father was ruined by his business partner — Elizabeth Warren remains an optimist. The Harvard Law professor, just named by President Obama to oversee creation of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB), believes that if consumers only understood the fine print on their mortgages, they would not have bought houses they could not afford. Or, if their credit card contracts had been written in plainer language, they wouldn’t have stretched to buy that Gucci handbag whose tag should have said “Out of Your League.”

More cheerfully, Warren believes that a brand new agency with a $500 million budget that crisscrosses numerous other financial oversight authorities will reduce the bewildering thicket of bank regulation. If only.

Warren has long petitioned for greater consumer protection against rapacious bankers, whose business models she describes as “making money through tricks and traps.” This is how she says the tricks and traps contributed to the financial crisis: Banks snookered consumers into taking on dangerous amounts of debt via purposefully incomprehensible credit card and mortgage contracts, and the resulting risky loans, which fed into the financial markets via securitization, nearly brought the country down.

More than Mere “Tricks and Traps”

Not only is this explanation rather insulting, it is nonsense. To imagine that millions of Americans became mired in underwater mortgages because they didn’t understand the terms of their loans ignores the country’s perspective at the time. People bought homes and assumed mortgages because they expected to make money on the deals – either long term, as has been the experience of most homeowners throughout our history, or quickly, by flipping properties. The financial collapse stemmed from a failure of imagination. No one — or almost no one — foresaw that home prices, which had risen steadily for decades, could actually drop.

Consider this: at the height of the boom, Freddie Mac experienced credit losses of only 1.1 hundredths of a percentage point on mortgages it bought or guaranteed — that’s 11 cents per $1,000 of value; losses were rare indeed. Hedge fund manager John Paulson made billions betting home prices would fall. That doesn’t happen unless nearly all the money is on the other side. The risk management gurus failed entirely to manage risk, because their models didn’t include a downturn.

The pitch for shorter, easier-to-read credit card and mortgage agreements is appealing. No one likes legalese and people have certainly been hurt by unexpected and costly rate changes and fees. However, the bulk of the most egregious “tricks and traps” have now been outlawed in our new credit card and mortgage legislation. Demanding cookie-cutter contracts from banks could hurt consumers and the economy.

Warren wants to limit the kinds of loans offered to people, and she wants banks to prove that unorthodox lending, such as to those with poor credit histories, “meets basic safety rules — things like whether a customer can read it in four minutes or less.” Banks lending to credit-challenged customers must be able to protect themselves against losses with fees and the option to increase rates — and those protections may require some fine print. If not allowed to construct loans to deal with unusual risks, banks may withhold credit from those with imperfect credit histories, slowing the recovery.

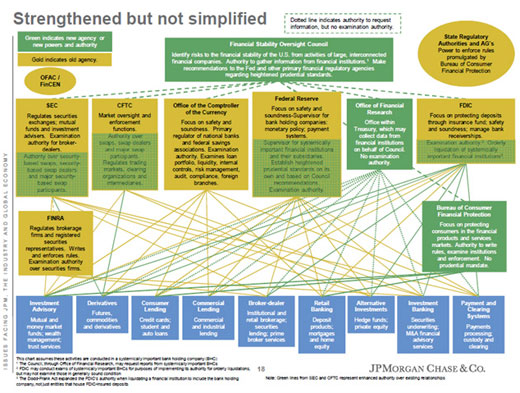

The CFPB itself could prove a dampener of credit. At a recent investor conference, Jamie Dimon, CEO of J.P. Morgan Chase, presented a slide showing the bank’s current overseers. It looks like something from the NASA archives:

There are nine separate regulatory groups overseeing various parts of the company, not including state agencies. For the consumer lending business, J.P. Morgan and its competitors will answer to the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, the Federal Reserve, a new Office of Financial Research, the FDIC and, of course, Warren’s new bureau. When advocating for a consumer agency, Warren argued that “with consolidated and coherent authority, the [new bureau] can harmonize and streamline the regulatory system.” She apparently missed the turf battles between federal agencies kicked off by the new financial reform bill.

In pushing for the creation of the bureau, Warren has likened it to the Consumer Product Safety Commission. Why should we regulate toasters, and not financial products, she asks. It’s a reasonable question, but would you put someone in charge of that effort who lost a finger to the contraption and harbors deep anti-toaster animosities? The entire now fragile economy depends on credit — there were more than 1 billion credit and debit cards in circulation last year. According to the Federal Reserve, 83 percent of small businesses use credit cards. The head of the new CFPB should bring a level head to this job, not a crusader cape.