When President Obama announced his National Export Initiative during his State of the Union address last January, some thought he had not gone far enough to boost exports and create jobs. But less than four months later, after the worst recession since the 1930s, exports are set to be a driving force in U.S. economic growth over the next few years while the global economy regains some of the balance it lost during the past decade.

That rebalancing has already begun. In 2006, as the economy surged, the U.S. trade deficit ballooned to a record 6 percent of gross domestic product. Imports flooded in, and dollars flew out, pumping up trade surpluses overseas. Foreign currencies provided capital to finance America’s credit boom and carefree consumption. As of this year’s first quarter, the trade gap has shrunk to 3.5 per cent of GDP, and the U.S. has cut its dependence on foreign capital by more than 40 percent.

Since the second quarter of last year, imports, adjusted for inflation, have surged at a 15 percent annual rate. Over the same period, however, exports also grew at a solid 15 percent clip. At that pace, exports would double in five years, as targeted by the Obama initiative. The growth in exports is already boosting U.S. employment in manufacturing, which will help Obama achieve another goal of his export initiative: to create an additional two million jobs over five years. The policy, which White House detailed in March, seeks to help small business sell products abroad, reform export control laws and redouble efforts to create trade agreements.

Unlike previous recoveries, the U.S. isn’t leading this global rebound, which will limit U.S. import growth while greatly benefiting U.S. exporters. Many overseas markets are booming. The global economics team at Morgan Stanley projects overall economic growth in China, India, Southeast Asia, Latin America and Canada to average about 8.3 percent in 2010 and 7 percent in 2011, with private domestic demand accounting for much of that expected growth. These regions account for nearly 60 percent of all U.S. exports. The euro zone, where growth continues to lag behind the U.S., accounts for only 15 percent of U.S. exports and only 10 percent of the trade deficit.

Over the past year, U.S. shipments to the world’s fast growth areas are up 28 percent, according to the Commerce Department’s March trade data. The trade deficit with Pacific Rim countries, excluding Japan, has narrowed by 15 per cent over the past year. China accounts for almost all of that gap; but even there, against China’s cheap currency, U.S. exports have soared 47 percent from a year ago, reflecting China’s booming growth.

Despite its ups and downs over the past year and continuing debate about its true value against the Chinese currency, the greenback, when weighted against all the countries with which the U.S. does business, is more than 20 per cent below its peak in 2002. A relatively weak dollar makes U.S. goods more competitive in overseas markets. The average level over the past two years is about where it was in 1997, when the trade deficit was barely more than 1 percent of GDP and exports were growing at a double-digit pace.

To a great extent, the global recovery taking shape is a traditional industrial rebound, and U.S. manufacturers are benefiting. In the first quarter, exports of computers and accessories were up 14 percent from a year ago. Semiconductor shipments rose 35 percent, while basic raw materials and supplies also increased 35 percent. Shipments by automakers jumped 56 percent from a year ago. Those items alone account for 46 percent of goods exported from the U.S. High-growth countries are also fueling strong demand for legal, accounting, financial and other business services.

As a result, U.S. factory production has picked up strongly, growing at a 6.9 per cent annual rate from the second quarter of last year through the 2010 first quarter, the fastest three-quarter pace since the tech boom in the 1990s. In March and April, an index of export orders compiled by the Institute for Supply Management stood at the highest levels since the late 1980s, when the dollar’s fall from super-high levels generated an export boom.

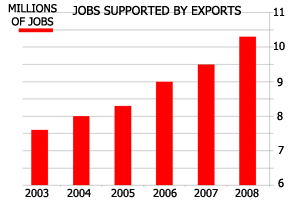

Before the global economy fell into recession, each $1 billion in U.S. exports supported 6,000 jobs, according to a recent Commerce Department study. Already, an increase of 101,000 manufacturing jobs so far this year accounted for more than 20 percent of the pickup in private-sector payrolls, and exports played a big role in those gains. The Commerce Department study shows that export-related jobs rose from 7.6 million in 2003 to 10.3 million in 2008, a period when inflation-adjusted exports grew about 7 percent per year

Exports stand a good chance to outperform that pace in coming years. Much will depend on the euro zone solving its looming fiscal crises in Greece and elsewhere without crippling global financial markets. More flexible exchange rates, especially in China, will also be important, and the U.S. will have to avoid protectionism, which could shut down global markets. Those areas will most likely determine the ultimate success of Obama’s efforts.