From billions in income supplements for households to trillions in guaranteed loans for businesses, fiscal policy has taken a central role in the government’s response to the Covid recession. According to Bloomberg’s Alaa Shahine, the new emphasis on fiscal management marks a major shift in policymaking circles, one in which central bankers are ceding the power they have held as primary managers of the economy since the 1970s.

“Fiscal policy is the big game in town now,” Stephen King, senior economic adviser to HSBC Holdings, told Shahine. “As a central banker, you have to accept in that sense you’ve lost a bit of power to the political process.”

Why fiscal policy has seen a revival. Central bankers have a limited set of monetary tools to respond to a crisis, centering on the use of interest rates to inject liquidity into the financial system. But those tools have little effect when interest rates are already historically low, and they do virtually nothing for workers losing their jobs and small businesses facing a crushing drop in demand.

Fiscal policy, on the other hand, allows lawmakers to get money directly into the hands of the unemployed and business owners, softening the blow of a recession. And it can target specific groups that need extra help, such as restaurants, airlines, schools or hospitals.

The lessons of 2008. The recovery from the 2008 financial crisis was sluggish, and much of the world found itself in the position Japan had stumbled into decades earlier, when interest rates dropped so low that monetary policy had little effect. “It was an early-warning sign that the world’s central banks might run out of steam, and bring fiscal policy back to the fore,” Shahine says.

Policymakers responded to the 2008 crisis with substantial fiscal stimulus – but withdrew it too soon, most experts now say. Since then, an increasing number of economists have changed their tune on the need to reel in fiscal stimulus quickly. Financial markets, too, seem to have lost their concerns about increased government spending, with bond buyers, including central banks, soaking up all the new debt the U.S. Treasury produces, and at very low rates.

Paul McCulley, the former chief economist at Pacific Investment Management, recently told Bloomberg's Joe Weisenthal and Tracy Alloway that he expects the expanded use of fiscal tools will be a permanent feature from now on. “Any pretense is over,” McCulley said. “We’re clearly living in a fiscal-policy dominated world.”

But there’s always a hitch (or two). One problem for the fiscal approach is that it relies on policymakers – which means politics are always involved. Most economists agree that the U.S. needs another round of stimulus spending, but lawmakers can’t agree on the size and scope of a new relief package. Shahine notes that politicians’ inhibitions about public spending are the last major barrier to deploying fiscal tools more extensively.

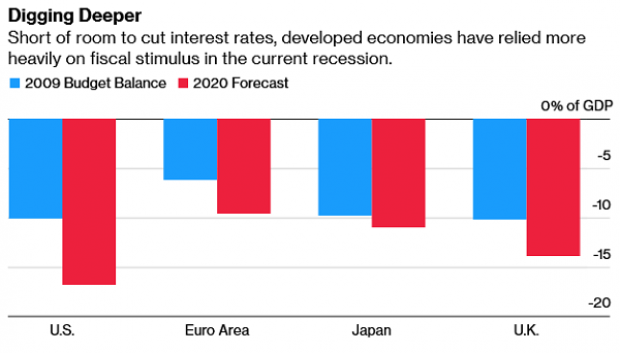

The other issue associated with the increasing reliance on public spending is bigger deficits, in the U.S. and other advanced economies (see the chart below, which shows how much larger deficits are now relative to GDP). And it looks like there’s a good chance those deficits will continue, at least in the short run, as both economists and financial markets come to see ongoing fiscal support as essential to sustaining the recovery.