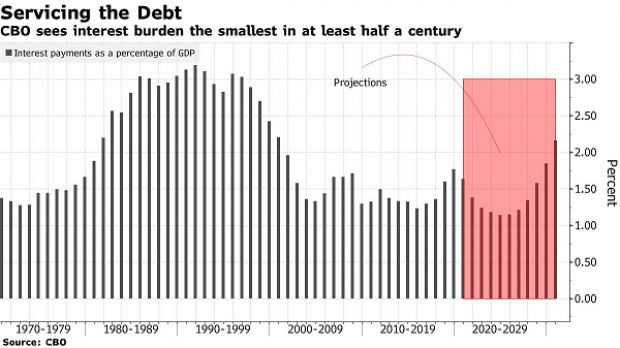

Interest costs on the national debt have fallen about 10% this fiscal year, even as the amount of debt issued by the U.S. Treasury has hit record levels, Bloomberg reported Friday. And over the next few years, the cost of servicing the debt held by the public – which now totals more than $20 trillion – will be cheaper relative to the size of the economy than any time since the early 1970s, according to projections by the Congressional Budget Office.

The reason is simple, Bloomberg’s Liz McCormick and Alexandre Tanzi say: interest rates plunged in the wake of the coronavirus pandemic, despite the record supply of debt, and are expected to remain low for years to come.

A focus on net cost. The federal budget deficit is expected to total $3.3 trillion this fiscal year, more than three times larger than the year before, but the average interest rate on U.S. debt has fallen from 2.4% to 1.7%, and it’s expected to continue to fall.

“While there’s been a lot of concern about the mounting debt, it hasn’t caused the problems that were anticipated by the doomsters,” Ed Yardeni of Yardeni Research told Bloomberg. “It’s not just a question of how much debt is outstanding, but what is the cost to service that debt.”

Room for more? The falling cost of the growing debt suggests that the U.S. will be able to issue more debt at low cost in response to the coronavirus crisis, should policymakers see the need to do so. “The U.S.’s debt affordability is quite OK, not stretched by any means,” Felipe Villarroel of TwentyFour Asset Management in London said. “We also look at what is the perceived use of the money a government is borrowing, which is now widely accepted as necessary.”

‘Bond vigilantes’ vanquished. Yardeni, who is credited with coining the term “bond vigilantes” 40 years ago to describe the investors who would supposedly pressure governments to limit their debt issuance by demanding higher interest payments, says conditions have changed. The Federal Reserve is now playing the opposite role of the 1980s investors, purchasing trillions of dollars’ worth of government debt to keep interest rates near record lows.

“If there were some bond vigilantes still out there to push the bond yields higher, then the Fed will target the bond yields,” Yardeni said.

What if rates rise? Plenty of policymakers and investors are worried about what happens if and when interest rates start rising, perhaps on the heels of surging inflation. “The Fed is greasing the system to make sure the financial markets are functioning well,” said Gary Pollack of Deutsche Bank. “But at some point in time the world will look different, and all of a sudden we are going to be stuck with a huge bill.”

Still, most economists say the current need for relief and stimulus outweighs any long-term concerns about the cost of the debt – with low interest rates making the decision that much easier. Writing at The Washington Post Friday, former Treasury chiefs Robert E. Rubin and Jacob J. Lew said that although they “share a history of concern about rising deficits and debt,” the coronavirus crisis calls for more federal spending. “[W]ith a pandemic raging amid an ongoing, deep recession, this isn’t the time to let deficits stand in the way of adequately addressing the crisis and the great need it has created,” they said.