Lawmakers clashed on Tuesday over the performance of the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act in a House Ways and Means Committee hearing titled “The Disappearing Corporate Income Tax,” with Democrats arguing that the law was far too generous to big business when it slashed the top corporate tax rate from 35% to 21%.

“Twenty years ago, we had a budget surplus,” Rep. Richard Neal (D-MA) said in his opening remarks. “Corporate tax revenues were twice as high as they are today. Now, corporations are paying less than ever, and corporate tax revenues are at their lowest level in history outside of a major recession.”

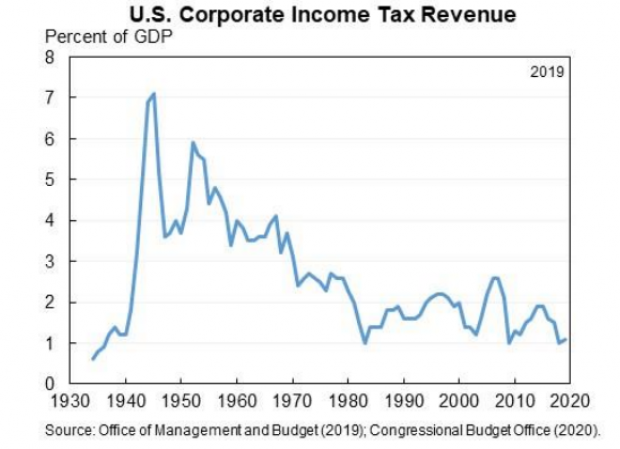

Jason Furman, one of three Democratic witnesses at the hearing, said in his prepared remarks that corporate income tax revenues equaled 1.1% of GDP in 2019, a level that “this is near the lowest since the 1930s (outside of recessions or their immediate aftermaths). U.S. corporate taxes are less than one half their historic average.” He also noted that corporate tax revenue as a share of GDP in the U.S. is now lower than in any of the top 30 developed countries – except for Latvia.

Furman, who served as President Obama’s chairman of the Council of Economic Advisers and is now a professor at the Harvard Kennedy School, said the low level of corporate income tax revenues were a big part of why overall tax collections relative to the size of the economy are near 50-year lows, coming to 16.3% of GDP in 2019, down from 17.2% in 2017.

And the long-term revenue losses are likely to be worse than first estimated, Furman said, citing a recent update to the Congressional Budget Office’s cost estimate for the tax cuts. CBO’s original analysis put the total revenue loss from the tax package at $1.5 trillion over 10 years, but the most recent revision to the budget outlook now puts the cost at about $2 trillion, with much of the increase related to larger-than-expected revenue losses on the corporate side.

Those losses, driven by generous rule-writing and interpretations of the 2017 tax law by the U.S. Treasury, are so substantial that they were deemed “tax cuts 2.0” by the liberal-leaning Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy. (You can read more about the revision in a recent blog post from CBO director Phillip Swagel, and in this report on how corporate lobbying affected the interpretation of the tax law from Jesse Drucker and Jim Tankersley of The New York Times.)

For their part, Republicans rejected the entire line of inquiry, arguing that tax revenues are rising, U.S. businesses are now more competitive internationally and solid economic growth over the last two years must mean that the tax cuts are working just fine. “The whole premise of this hearing is false,” said Rep. Kevin Brady (R-TX), one of the architects of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act. “Corporate taxes aren’t disappearing, they are growing — more than 12% last year. And according to CBO, corporate revenues are set to rise over the next decade both in real dollars and as a percent of GDP.”

Still, the sole Republican witness, former CBO director Douglas Holtz-Eakin, who now runs the conservative American Action Forum, couldn’t deny that the tax cuts have in fact reduced corporate tax revenues. “TCJA reduced corporate income tax receipts; receipts in fiscal 2019 were $230 billion, down from $344 billion in 2015. This drop was to be expected,” he said. At the same time, Holtz-Eakin noted that the CBO projects a steady increase in corporate tax revenues in the coming years. And he argued that it’s still too early to make any final judgments on the tax package, which, while “imperfect,” deserves some degree of credit for recent economic performance.