The average age of the U.S. population is rising as the baby boomers sail into their golden years, but a statistically older population may not be as problematic as some experts think.

According to a new analysis from Eugene Steuerle and Damir Cosic of the Urban Institute, “traditional measures dramatically overstate aging problems.” Today, older citizens have “better health, greater capacity to work, and a more active lifestyle,” they write, which means that many of them will postpone the problems of the “truly old” for many years.

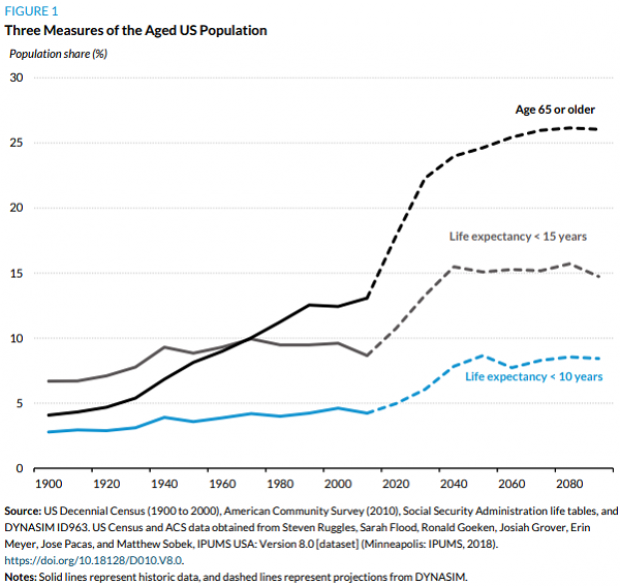

In addition to chronological age, Steuerle and Cosic argue, policymakers should consider measures that take into account ongoing changes in longevity and mortality rates. If seniors are living longer and in better health, then it makes sense to break down their population into subgroups that reflect these changes. Along those lines, the authors analyzed the U.S. population using three different measures of “old” – 65 and older, those with a life expectancy of less than 15 years, and those with a life expectancy of less than 10 years. The results (see the chart below) indicate that while the over-65 population will continue to grow for many years to come, as expected, the number of the “truly old” (those nearing their deaths) will stabilize at a much lower percentage of the population.

The analysis has implications for social welfare policy, including Medicare and Social Security. Those programs were built using out-of-date assumptions about longevity, the authors argue, which may now distort efforts to aid the truly old as they provide benefits for millions of ‘younger’ old people. While they don’t explicitly advocate for an increase in the Social Security retirement age, Steuerle and Cosic say that, “If the retirement age in programs such as Social Security had been adjusted for longevity or improvements in life expectancy, Social Security would be running surpluses at existing tax rates not only today but even after the effects of baby boomers’ retirement had played out. Such surpluses could have been used to maintain higher benefits for those in need, those near poverty, and those with the chronic and long-term care needs that come in the last years of life.”