Senate Republicans, depending on where they currently stand on their leaders’ latest proposal in the battle to overturn the Affordable Care Act, will either spend their weekend having their arms twisted to support the Better Care Reconciliation Act, or being enlisted in the effort to twist their colleague’s arms. Time is running short for the GOP to produce a budget reconciliation bill before the fiscal year ends on September 30, and the next two months may represent the GOP’s last shot.

The bad news is that, for reluctant Republicans, many of their concerns about the bill’s impact on low-income Americans have not been addressed by revised versions of the legislation. Some, like Maine’s Susan Collins and Nevada’s Dean Heller, are concerned about the impact that the proposal’s cuts to Medicaid and its changes to the formulas used to calculate premium subsidies will have on the out-of-pocket costs that the poor have to bear.Related: Senate Republicans May Try to Skirt CBO Score on Health Bill

An analysis by Loren Adler and Paul B. Ginsburg of the Brookings Institution, released this week, isn’t likely to make them more enthusiastic about the Senate bill.

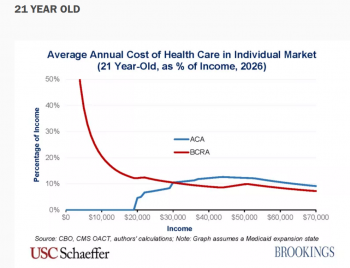

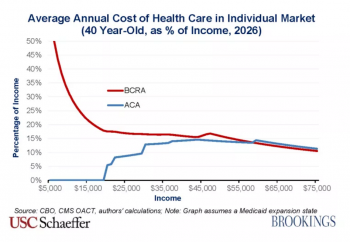

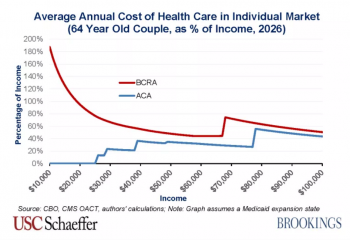

Adler and Ginsburg took the legislative language released by the Senate this week and translated it into dollars and cents for Americans across a range of age and income categories. The results were plain. Under the Senate GOP plan, low-income Americans who have to buy insurance on the open market would pay more for their coverage, in most cases much, much more.

“The most striking finding is that the BCRA would lead to a large increase in average annual health care costs for those with lower incomes, whatever their age and family type,” they write.

While the increased costs would be felt by Americans across most age and income brackets, it would be particularly pronounced for older Americans who are not yet eligible for Medicare.

Related: McConnell Infuriates Some Conservatives by Preserving Two Big Obamacare Taxes

“For example, a 64-year-old couple earning a combined income of $28,000 would go from average annual costs equal to 13 percent of their income under the ACA up to 70 percent of their income under the BCRA,” they write.

“The magnitude of this change stems in large part from the elimination of the ACA’s cost-sharing subsidies, which effectively reduce low-income enrollees’ out-of-pocket costs, and that unsubsidized average out-of-pocket costs are particularly high for a 64-year-old couple.”

In fact, there is no income bracket for a 64-year-old couple making less than $100,000 per year in which health insurance coverage as a percentage of income would not rise under BCRA.

The bill would result in modest premium decreases as a percentage of income for younger Americans. A 21-year-old earning $30,000 per year or more would pay slightly less under the BCRA than under the Affordable Care Act.

Related: Feds' Big Bust: $1.3 Billion Health Insurance Fraud Takedown

For a 40-year-old, the threshold is higher: It isn’t until income hits $60,000 per year that the percentage of income spent on health insurance under the BCRA falls below that spent under ACA. And even then, the difference is tiny.One of the overarching goals of the GOP in assembling an Obamacare alternative was to lower consumers’ insurance premiums. If the Brookings analysis is correct, the bill currently under consideration succeeds, but only for a smaller, and relatively more wealthy segment of the population.