Tapping Elon Musk's SpaceX to launch some of its satellites is only the beginning in a larger top-to-bottom rethink of the way the U.S. Air Force approaches its operations in space. Air Force officials want to move faster when addressing emerging threats and future missions in orbit, and it's increasingly looking to start-ups to address a deepening sense that America's dominance in space is eroding.

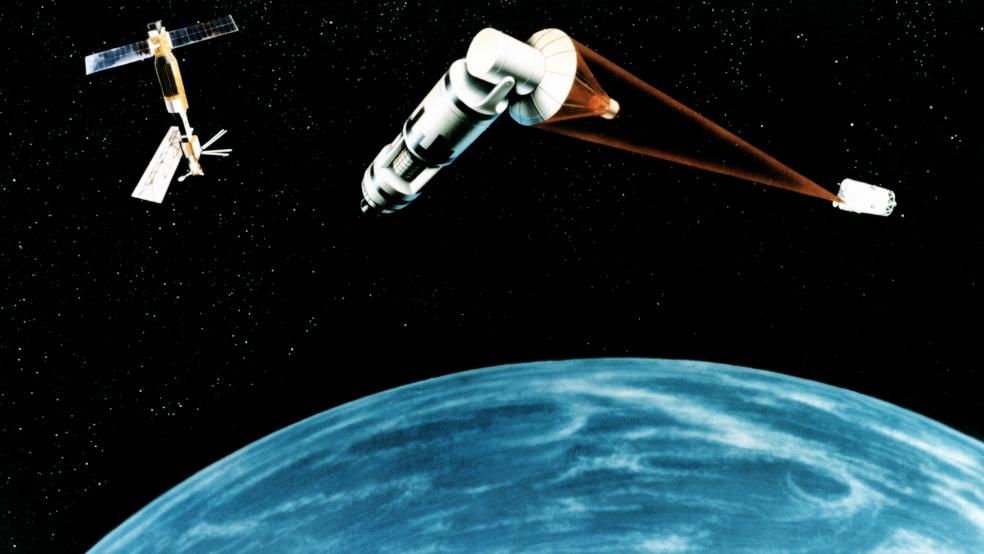

The goal: to protect our satellites and spacecraft from cyberwarfare and missile attack. This is critical, since space weapons could be used to compromise navigation, surveillance, communications and other functions in wartime or during a national emergency.

Related: The $3,000 Rifle That Could Make the US Marines Even More Lethal

The shift comes as the space domain is already receiving increased attention from lawmakers and the Department of Defense and, in the years ahead, likely more defense dollars as well. The Pentagon's Joint Interagency Combined Space Operations Center — known by the unwieldy acronym JICSPOC — was recently rebranded the National Space Defense Center, and under pressure from Congress, the Air Force this month created a new position for a three-star general that will serve as a kind of space czar, advising the Air Force Secretary and the Joint Chiefs of Staff.

That general will "come to work every day focused on this: making sure we can organize, train and equip our forces to meet the challenges in this domain," Gen. Jay Raymond, head of Air Force Space Command, said last week at the National Space Symposium in Colorado.

Part of that job of training, organizing and equipping the U.S. military's space forces could fall to smaller, more agile companies outside of the Air Force's conventional supply chain of major defense and aerospace contractors, Raymond suggested. Though procurement programs for new satellites and rockets have long been measured in years — sometimes decades — threats and challenges in the space domain are now moving much faster as potential adversaries like China hone their capabilities in space. "I really see a need to go fast," he told his audience. "We are developing ways to go fast."

Though international agreements such as the 1967 Outer Space Treaty prohibit the positioning of weapons in space, the Pentagon is increasingly aware of the vulnerabilities there. As more and more countries develop advanced rocketry programs and cyber capabilities, it grows more and more difficult to defend critical military satellites that provide U.S. air, ground and sea forces with intelligence, communications, navigation and targeting capabilities.

In a serious conflict with a sophisticated adversary — Russia or China, for example — those satellites would likely be among the first targeted. Both countries (as well as the United States) have successfully tested anti-satellite weapons capable of destroying satellites in orbit. Military officials have also expressed repeated concerns about cyber vulnerabilities that could allow an enemy to jam satellite transmissions or otherwise disable space assets remotely.

Related: With Iran in His Crosshairs, Trump Has One Risky Chip to Play

The space arms race

"We are at a time when space is contested like never before," Rep. Mike Rogers, R.-Alabama and chairman of the House Armed Services Strategic Forces Subcommittee, said at last week's space symposium. In those remarks, Rogers advocated for a future in which a separate space force might exist within the Department of Defense, carved out of the Air Force as a standalone service much as the Air Force was separated from the Army when it became clear that aerial combat and operations required higher prioritization — an organizational change the Air Force would undoubtedly oppose.

Concerned about trend, the Pentagon wants to shore up capabilities in space defense and warfare as well. It is looking beyond its traditional supply chain — where new satellites and rockets can take years and billions of dollars to develop — to technology start-ups that may be able to deliver both hardware and software capabilities faster and less expensively.

The most notable and visible of these relationships is with SpaceX, which was certified in 2015 to launch certain kinds of military satellites for the U.S. Air Force, beating out longtime military launch monopoly United Launch Alliance — a joint-venture between Boeing and Lockheed Martin — for its first Air Force contract in March of the following year. Last month Space X won its second contract from the U.S. military to launch an Air Force GPS satellite on an upgraded Falcon 9 rocket sometime in 2019.

But the Pentagon is interested in other hardware as well — not only newer, less-expensive rockets that can travel to space and back to Earth for quick reuse but also multipurpose, adaptable satellites that can launch quickly to replace satellites disabled by an adversary, and orbiting robots that can refuel and repair satellites already in orbit.

Related: The Army Has a New Supergun That Can Blow Apart a Tank

Partnering with tech upstarts

Where satellite data is concerned, the Department of Defense has in recent years expanded its effective fleet of imaging satellites by tapping into data collected by commercial space start-ups. In 2012 it inked a deal with Longmont, Colorado-based Digital Globe, allowing the Air Force and other military branches to quickly download and utilize the company's ultrahigh-res commercial satellite imagery for use in military and intelligence applications. More recently, the Pentagon has entered into a $20 million arrangement with small-imaging satellite company Planet, a San Francisco-based firm whose constellation of small-imaging satellites can offer the agency imagery of the entire globe refreshed every couple of weeks.

"It's an opportunity to reach out and work with those companies and see what kind of new and enhanced resources they can offer that might allow the Air Force to do things differently," says Carissa Christensen, CEO of Bryce Space and Technology, an Alexandria, Virginia-based consultancy. "So I think there's a lot of openness on the part of the military to working with these companies. And of course these companies are trying to operate in space less expensively, and the government is under budget pressure across the board, so that's attractive as well."

The government is also interested in software solutions that can help the Air Force and other U.S. agencies quickly make sense of all that data collected by both commercial satellites and the Pentagon's own fleet of imaging and intelligence-gathering satellites. For example, last month the Pentagon's blue-sky research lab, known as DARPA (for Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency), signed a $1.5 million three-year agreement with Descartes Labs, a privately held start-up based in Los Alamos, New Mexico, that uses machine learning to parse satellite imagery for meaningful insights.

Descartes has in the past used its technology to create a global view of the world's agriculture (it has previously used its imagery to predict U.S. corn harvests more accurately than the U.S. Department of Agriculture). Noting the correlation between food insecurity and political instability, DARPA has hired Descartes to monitor and predict wheat output across the Middle East and North Africa in an attempt to better predict regional unrest.

Particularly where emerging computational tools, like computer vision, machine learning and other technologies grouped under the heading "artificial intelligence" are concerned, technology start-ups offer some compelling advantages over more conventional defense contractors — particularly where adaptive cyberdefense is concerned. For those officials charged with safeguarding America's orbital military infrastructure, the relationship between software, cybersecurity and space has come into acute focus over the past few years, making relationships with Silicon Valley all the more compelling.

"I think it's very fair to say that there is a deep appreciation within the Defense Department and certainly within the Air Force for the interplay of space and cyber capabilities and the importance of coordination between space and cyber," Christensen says. "I don't think that's lost on anybody."

This article originally appeared on CNBC. Read more from CNBC:

Goodbye, Florida: Here's the new retirement hotspot.

Investors are right to be concerned about the market, expert says