Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump have slogged their way through a brutal campaign season, and are now just days away from finding out which of them will become the next president. But if they each take a few minutes to read a new paper from the Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center and the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget, they might decide they don’t really want the job after all.

That’s because the main takeaway of the piece, “A Lame Duck President in 2017?,” is that the incoming chief executive will have to focus on managing a collection of expensive programs that were put in place years ago rather than implementing new and original ideas. Existing programs call for considerable mandatory spending and are designed in such a way that they swallow up most or all of the revenue increases the government sees from economic growth.

Related: This Stock Market Indicator Points to a Trump Win

“We usually think of lame ducks as politicians who have lost influence to their successors, but the next president could enter office with his or her influence already lost to his or her predecessors,” write C. Eugene Steuerle and Caleb Quakenbush of the Urban Institute, and Maya MacGuineas and Tyler Evilsizer of CRFB.

“The growing revenues that accompany economic growth traditionally provide a way for government to address new needs and priorities. But because of the increasing dominance of autopilot programs with built-in growth, all those revenues plus additional borrowing are required to pay for health and retirement expenses and interest on the debt.”

(This is familiar ground for Steuerle, who wrote about the issue in his 2014 book, Dead Men Ruling: How to Restore Fiscal Freedom and Rescue Our Future.)

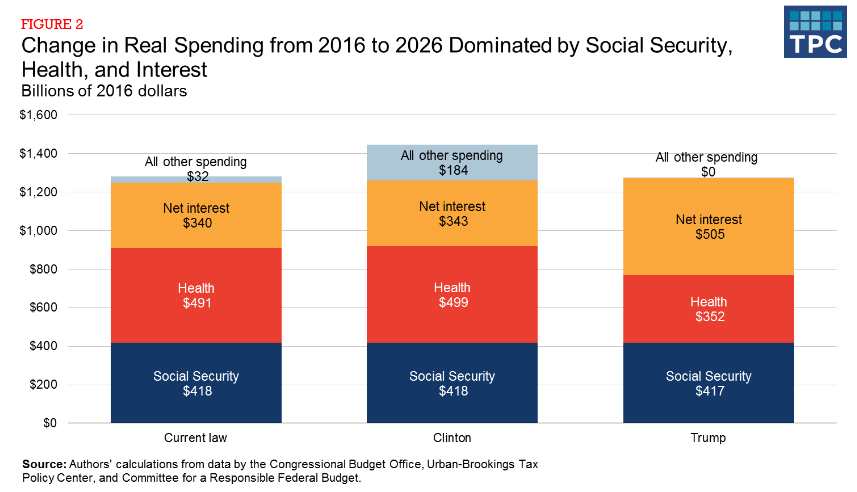

Unsurprisingly, the big drivers of spending are the usual suspects: healthcare programs like Medicare and Medicaid, Social Security, and interest on the ever-growing national debt.

Related: How Much Does Wall Street Love Hillary? Let’s Count the $78 Million Ways

In short, the next president is going to have to come to terms with the fact that not only is future revenue spoken for, but so is much of the country’s future borrowing.

Even with no changes to current law, the Treasury Department’s revenues are expected to increase by about $850 billion each year through 2026. The candidates’ tax plans that would alter that, with Clinton’s increasing revenue modestly and Trump’s slashing it dramatically.

“However,” they write, “inflation-adjusted spending is projected to grow $1.25 trillion in 2026 relative to 2016 because of increasing health, retirement, and interest expenses. In other words, 150 percent of new revenue a decade from now is pre-committed to spending growth scheduled under current law.”

That, they argue, means that the next president “will be left with almost no ability to do anything new, much less respond to an unexpected economic, environmental, or defense challenge. Other policy goals (e.g., universal prekindergarten, leaner government, or lower taxes) will be much harder to realize if there is no room in the budget left for them.”

Their conclusion -- not really surprising, given the data -- is that unless Congress and the next president resign themselves to some combination of sharp budget cuts and increased tax revenue, the next administration and those that follow it will be reduced to the role of caretakers for a crumbling system.