While a handful of states including West Virginia, New York and Indiana have made important strides in reducing major shortfalls in their employee pension plans, many others are just treading water or losing ground, according to a new study by the Pew Charitable Trust.

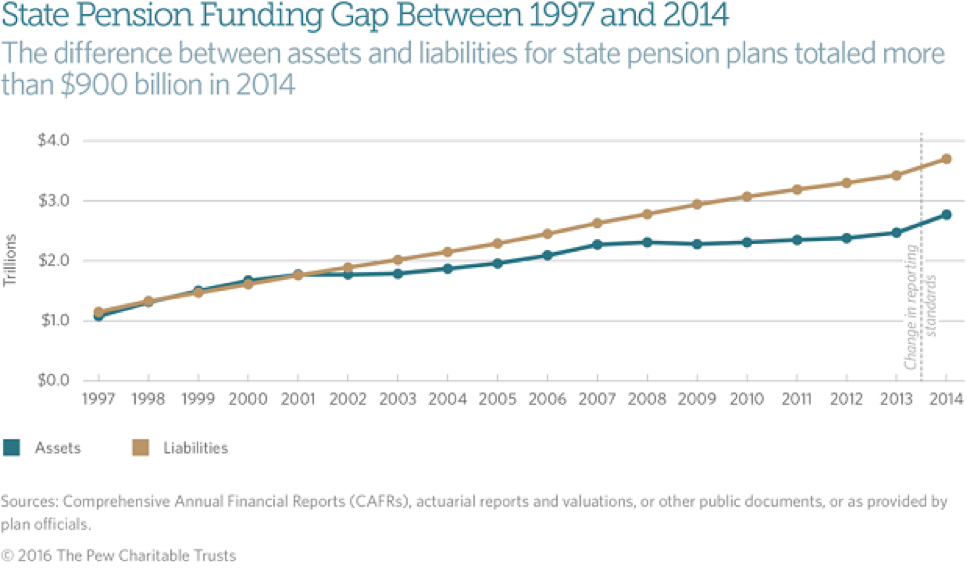

A year after the organization sounded a dire warning about a widening gap between assets and obligations, the picture has improved just slightly. State-run retirement systems reported shortfalls totaling $934 billion in fiscal 2014, the latest figures available, which was a slight improvement over the $969 billion deficit from the previous year.

Many states were fortunate in making smart investments that helped chip away at the shortfall, but those good times are over. Now, unless state governments undertake concerted policies to raise revenues or somehow reduce their obligations -- other than through budgetary gimmicks -- the gap will expand to well over $1 trillion in subsequent years, according to the authors of the report.

Related: Fiscal Shame: Illinois Has Gone Nearly a Year Without a Budget

When combined with the shortfalls in local government pension systems, the total state and local pension debt likely exceeded $1.5 trillion in fiscal 2015 – an historically high level of debt as a percentage of the overall U.S. economy.

“The gap between the pension benefits that state governments have promised workers and the funding to pay for them remains significant,” the report stated. “Many states have enacted reforms in recent years to help shrink that divide, but they also have benefited from strong investment returns.”

“Over the long term, however, these returns are uncertain,” the report added. “In addition, many states have not made contributions that would reduce plan debt under expected returns.”

Since the worst of the Great Recession, state governments across the country have struggled to overcome a deluge of red ink in their employee retirement plans, as few were able to even come close to matching assets with projected long term demands. Caught in a squeeze between a rapidly aging population, tight operating budgets and strong resistance from unions to increase employee contributions or reduced retirement benefits, many states have simply allowed the problem to fester.

A year ago, Pew reported that the gap between what states have pledged to retirees and how much they were actually saving to fund those payments totaled $968 billion as of 2013, a $54 billion increase in debt over the previous year. The subsequent reduction in pension debt in 2014 was primary due to highly successful investments, with public plans averaging a 17 percent rate of return in 2014, according to Pew.

Related: States Keep Using Gimmicks to ‘Balance’ Their Budgets

But those boom times were short-lived, and the return on subsequent investments by state employee pension programs in fiscal 2015 averaged only three percent. Even worse, return on investment sank into negative territory during the first three quarters of fiscal 2016.

One recent case in point: The California Public Employees Retirement System announced late last month that its investments returned a paltry 0.61 percent during the fiscal year that ended June 30 – falling ridiculously short of its 7.5 percent target, according to Fortune. Currently, CalPERS has 68 cents in assets for every $1 of pension liabilities. But even that was premised on the state meeting its 7.5 percent investment return target.

The Pew study stressed that state and municipal government policymakers are misguided if they are counting solely on big investment returns to close their funding gaps over the long term. Policymakers need to follow funding strategies that put them on track to pay down pension debt.

“The differences we see between states that have well-funded pensions and states with pension funds in distress are largely the result of policy choices,” said David Draine, a senior researcher at Pew. “Everyone had the dot-com crash, everyone had the Great Recession. Some states had sustainable policies in place to manage those risks, others simply let pension debt accumulate, which is going to put a burden on taxpayers and those who depend on public services going forward.”

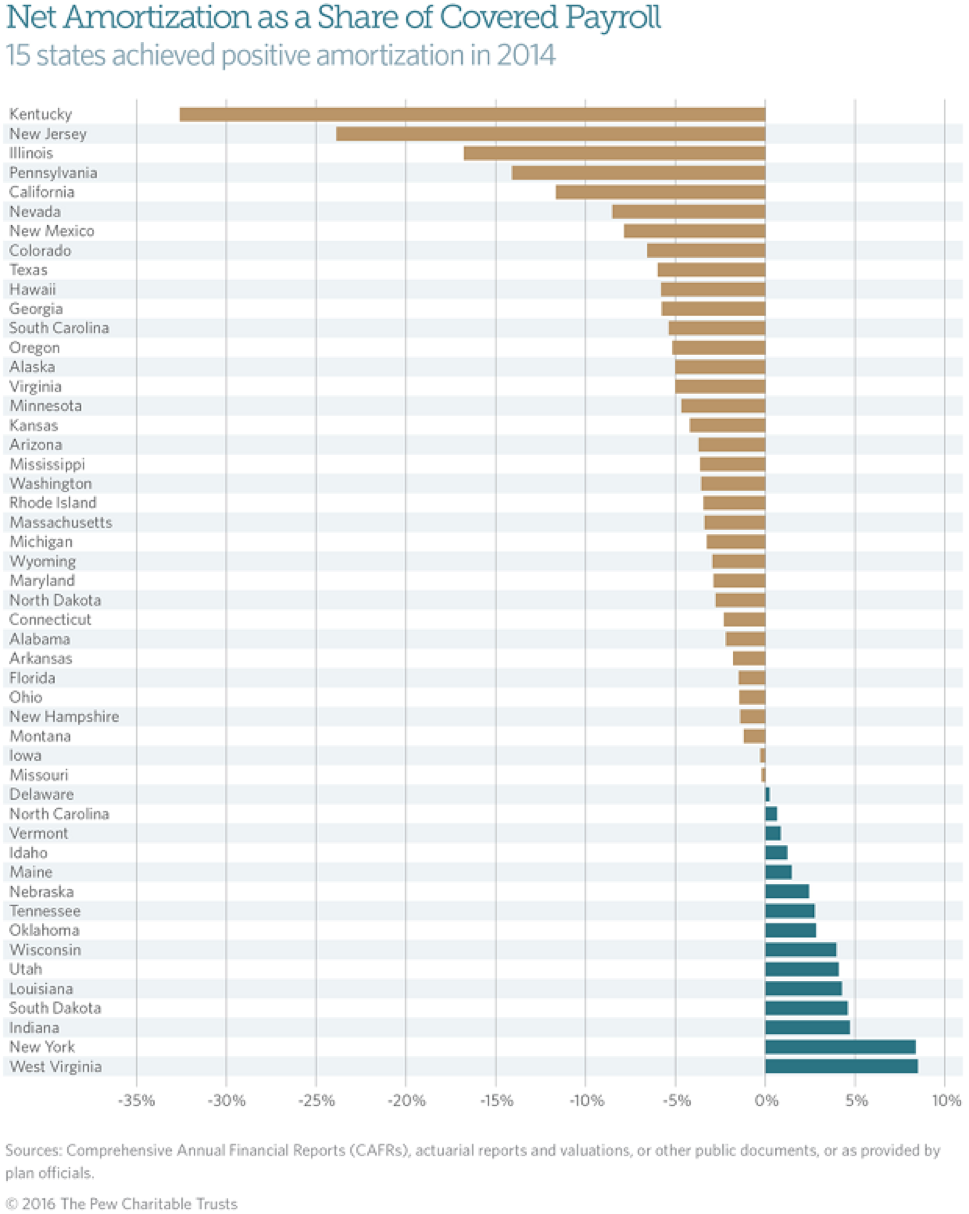

The study uses a “net amortization” yardstick for measuring the relative success or failure of all 50 states in making the necessary payments to meet the cost of retirement benefits while gradually shrinking their unfunded liabilities. In Pew’s first report card using this metric, 15 states were found to be currently following policies that meet the “positive amortizing benchmark,” while the remaining 35 states are falling short.

Related: Anti-Tax GOP Governors Find It Hard to Hold the Line

The ten worst performing states were: Kentucky, New Jersey, Illinois, Pennsylvania, California, Nevada, New Mexico, Colorado, Texas and Hawaii.

The ten best performing states were: West Virginia, New York, Indiana, Louisiana, Utah, Wisconsin, Oklahoma, Tennessee, Nebraska and Maine.

Of the 10 states with the strongest results on positive amortization, seven have historically paid about 95 percent of the so-called actuarial required contribution (ARC). However, three of the states — Nebraska, Oklahoma and Louisiana — reported paying less than full ARC payments in recent years. “Still, the three continued making progress in reducing pension debt,” according to the report.

Oklahoma’s relatively impressive performance stems from a 2011 change in the cost of living adjustment for retirees that saved the system millions of dollars. After that dramatic – albeit unpopular – policy shift, the state’s new contribution policy was adequate to pay down the remaining pension debt, the report stated.

Kentucky, New Jersey, Illinois, and Pennsylvania showed the largest negative amortization. “Plans in these states face significant challenges and have low funded ratios,” according to the report. “And without the strong overall investment returns in 2014, net amortization shows that these states would have lost further ground.”

In describing the disparity between states doing well and poorly in addressing their long term pension shortfalls, Draine said that “ultimately it’s a question of whether you pay now or pay later.”

“When we see states that are allowing their debt to grow and failing to make progress on getting the full funding, you end up in a situation where there’s reason to be concerned. Do these debts grow? And do they crowd out important public investments in the future? We’re seeing that impact happen already in places like Illinois and New Jersey, where increasing pension debts and the inability to manage those costs have done real fiscal harm.”