At the beginning of the Democratic convention, it looked like the parties had reverted to type: The Republicans had (pretty much) unified around their nominee, focused more on their common enemy than on their minor disagreements, while the Democrats were back to their fractious ways. Boos rang out through the convention hall in Philadelphia, and establishment Democrats tore their hair out at the prospect that their carefully laid plans might be blown to shreds.

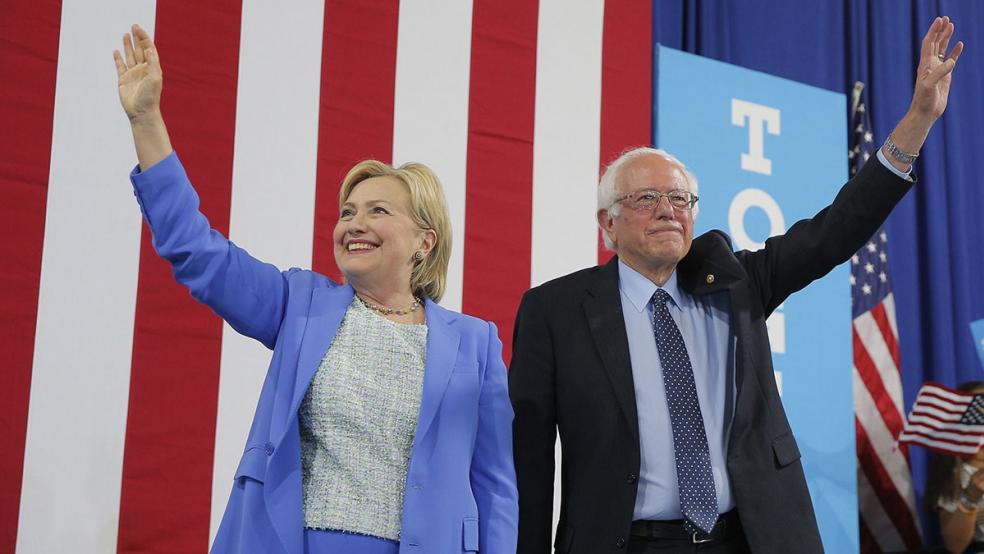

But then it all came together. It took some negotiating, but not only did Bernie Sanders offer Hillary Clinton a full-throated endorsement, his staff worked with Clinton's people to quell the kinds of disruptions that had marred the convention's first night. By the time it was all over, the party looked unified and all but a small number of disgruntled Sanders dead-enders had joined in.

Related: Why Clinton’s Plan to Boost Worker Pay Is Doomed to Fail

All of which raises a real question: What if there was never much of an insurgency to begin with? What if it was mostly sound and fury, signifying little more than an ordinary primary campaign of the kind parties have every four years?

I say this not to belittle Sanders' remarkable achievement. A grumpy 74-year-old Jewish socialist with a Brooklyn accent thicker than a pastrami on rye from the Carnegie Deli got millions of votes, won nearly two dozen primaries and caucuses, and nearly took down the party's obvious favorite. But we may have been fooled into thinking that the Sanders insurgency was more of a categorical rejection of the Democratic Party and its now-nominee than it actually was.

That impression reached its apogee in Philadelphia, but it's important to understand that the convention conveyed two misleading impressions of left-wing opposition to Clinton. First, it made that opposition seem like a phenomenon within the Democratic Party, a homegrown insurgency. But as I argued recently, that wasn't really true. Many of the people who rallied around Sanders weren't Democrats before this election, and they won't be Democrats afterward. They're leftists who not only view the Democratic Party as irredeemably corrupt, but see liberals as their main enemy and always have.

While we've seen some of this same tendency in the last few years among the Tea Partiers who so relentlessly fought against the Republican Party's leadership, such tensions have a much longer history on the left. There have always been leftists who reserved their most intense enmity not for those farthest away from them on the political spectrum, but for those reasonably close by who were seen as insufficiently pure and righteous in their analysis, their proposals, or their tactics.

Related: Clinton Skates Through Fox News’ Softball Interview

I'm not talking about the majority of people who voted for Sanders, or even the majority of Sanders delegates at the convention — and that's just the point. The people protesting Clinton outside and booing her inside were just a tiny fraction of Sanders' supporters, and now that this primary is over they'll do exactly what they were going to do all along: Support a third-party candidate like the Green Party's Jill Stein, if they vote in the presidential race at all.

The other factor that made vehement left-wing opposition to Clinton look larger than it is was that so many of those opponents were all gathered in one place, a place that was also occupied at the same time by hundreds of journalists looking for colorful quotes. Which, of course, is why so many leftist Clinton opponents came to Philadelphia: It offered an opportunity to have their voices amplified by the media, the kind of opportunity you only get once every four years. Now that the convention is over, they'll return to their hometowns and have a lot more trouble garnering the attention of the media. And before you know it you'll wonder why they ever seemed like such a potent force of disruption.

Don't be surprised if Stein gets no more votes this year than she did four years ago. In 2012 she managed 469,000 votes, or about one-third of one percent. It was dramatically less than the Green Party's best showing, which of course came in 2000 when Ralph Nader won 2.9 million votes, or 2.74 percent, including 97,000 votes in Florida, which you'll recall ended up being rather important to the final outcome.

As Jonathan Chait notes, Stein has been reduced to arguing that the only way to stop Donald Trump is to get him elected president of the United States, which makes about as much sense as anything else the average Bernie dead-ender will say when you ask them whether the specter of a Trump presidency might give this election a unique urgency that demands a more pragmatic approach to their votes. Nor will they be swayed by the fact that the man who was their champion (until he became just another establishment sellout) attained the highest degree of political influence in his long career when he joined the Democratic Party — and he'll have to stay there if he wants to hold on to it.

But that's not what those leftist rebels are after for themselves — which is perfectly fine. They should pursue their political goals in whatever way they think is most effective and most true to themselves. But they aren't going to threaten Hillary Clinton's chances of becoming president. That's up to her, and Donald Trump.

This article originally appeared on The Week. Read more from The Week:

The most Republican state in the Union might go blue this fall

Donald Trump's confusing explanation for how he avoided the Vietnam draft

In a big first, Republican congressman says he's voting for Hillary Clinton