About 25 percent of the $650 billion of annual spending on Medicare goes for the treatment and care of elderly people in the final year of their lives, according to a new study. Per capita spending is nearly four times higher for those who die than for survivors.

In the long-standing national debate over how far the government should go in stretching limited resources to keep the oldest and sickest people alive, the conventional wisdom has been that the vast majority of beneficiaries making claims on Medicare in the final year of their lives are wizened people in their 80s or 90s confined to nursing home hospital beds.

Related: Rising Health Care Costs Will Push the Nation’s Debt Into High Risk

But the new study by the Kaiser Family Foundation released on Thursday pokes a big hole in that assumption.

Of the 2.6 million Americans who died in this country in 2014, eight out of ten were enrolled in Medicare, the premier national health care program for seniors. However, the Kaiser study found that Medicare spent significantly more per capita on medical services and treatment for people in their late 60s and early 70s than on much older beneficiaries.

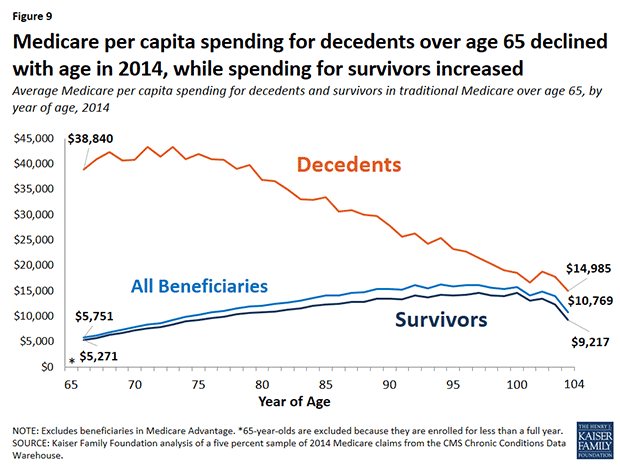

Indeed, the analysis concluded that per capita Medicare spending at the end of life actually declines with age – peaking at $43,353 for those 73 years old and then gradually declining to $33,381 for 85-year-olds and just $27,779 for people 90 and older.

The report says that it’s hardly surprising that a “disproportionate share” of Medicare resources goes to beneficiaries at the end of life. Many of those beneficiaries suffer serious illnesses like Alzheimer’s disease, congestive heart failure, kidney problems, cancer and multiple chronic conditions that require inpatient hospitalization, post-acute care and hospice.

Related: U.S. Medicare End-of-Life Counseling Off to Slow Start

Yet per capita spending for inpatient services “is lower among decedents in their eighties, nineties, and older than for decedents in their late sixties and seventies, while spending is higher for hospice care among older decedents,” the report states.

“These results suggest that providers, patients and their families may be inclined to be more aggressive in treating younger seniors compared to older seniors, perhaps because there is a greater expectation for positive outcomes among those with a longer life expectancy, even those who are seriously ill,” notes the report, which was written by Juliette Cubanksi, Tricia Neuman, Shannon Griffin and Anthony Damico.

The analysis included all people 65 and older who automatically qualify for Medicare, as well as some younger people with disabilities or who qualify because of renal disease. More than half of these beneficiaries were 80 or older at the time of the study.

From a strictly budgetary standpoint, the beneficiaries who were in the final year of their lives were unique. They received one in every four dollars spent by the health care program while representing just four percent of the overall Medicare population.

Related: Trump and Clinton Fiddle While Long-Term Debt Is Set to Surge

Per capita Medicare spending was nearly four times higher for those who died in 2014 than others who survived -- $34,529 for the decedents to just $9,121 for those who lived.

For years, medical experts, lawmakers, patient advocates, family members and others have debated end-of-life treatment for the nation’s elderly and the value of attempting to extend life as long as possible. That debate grew especially heated in 2009, when then-Alaska governor Sarah Palin charged that a provision of the Affordable Care Act which was then being debated in Congress was tantamount to the creation of “death panels.”

The provision in question would have paid doctors for providing voluntary counseling to Medicare patients about living wills and end of life care alternatives. Palin’s claim was widely debunked, but the provision was dropped from the bill amid rising public concern.

Related: Life at All Costs: The Mid-Death Crisis

A recent revision to the Medicare payment policy allows reimbursement of physicians who have conversations about advance care planning with their patients. Although that program has gotten off to a slow start, the study said that the revised payment policy “could bring about changes that better align services delivered with patient preferences and that also potentially reduce the costs associated with care at the end of life.”