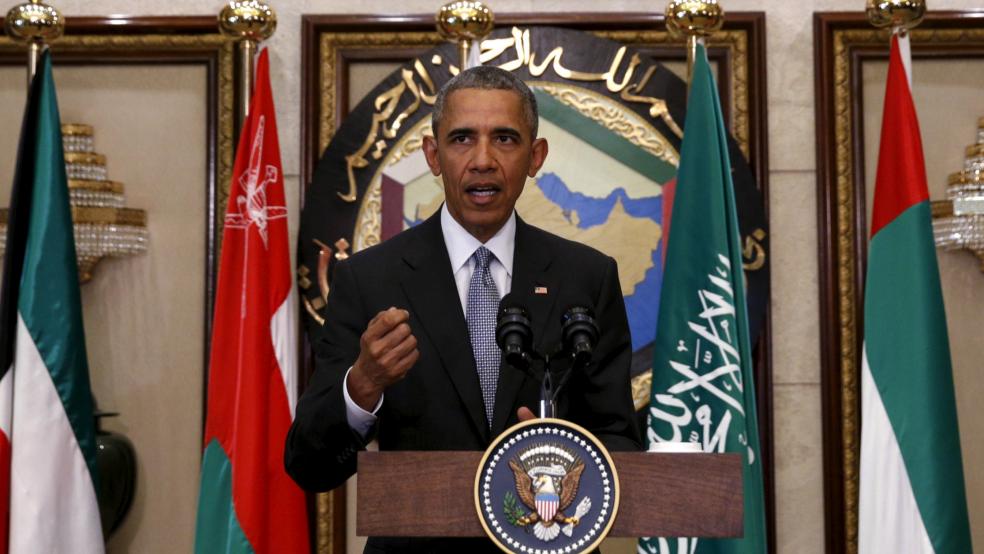

There are several reasons why today’s summit in Riyadh has little chance of overhauling the tense U.S.-Gulf partnership, even aside from President Barack Obama publicly calling his Middle Eastern partners “free-riders” and advising them to “share the region” with bellicose Iran. None is more important than the U.S. struggle to identify a long-term strategy that reflects our genuine political-military commitment to our partners and preserving Gulf security.

We are struggling in large part because we still haven’t solved an age-old dilemma in the Middle East. We have partners who seem committed to security cooperation; many of their contributions to counterterrorism and other security issues have been extremely helpful. But most Middle East states have vastly under-performed in their efforts to make the political reforms that would be the most critical enabler of security and stability. As long as this imbalance exists, regional security and collective interests will continue to be at risk.

Related: 8 Weapon Systems the U.S. Is Selling to Saudi Arabia

Yet we have done almost nothing to explore how we might overhaul our own efforts in the region. If our Gulf partners are guilty of falling short on the issue of reform – and most of them are – we also are guilty of repeating an outdated Gulf strategy and expecting it to generate different results.

Pax Americana in the Gulf is changing and perhaps over. The influence we have enjoyed since Great Britain withdrew most of its military forces from the region in the early 1970s is gone. Why? It’s no secret: iron-fisted autocracies, the Internet, generational shifts, regional transformation and chaos resulting from the Arab uprisings, 40 years of warfare, the Islamic State, and U.S. priorities elsewhere. We’re now seeing an acceleration of the transition from a Gulf security architecture with almost exclusive U.S. access and control to a more penetrated system in which the United States is militarily dominant, but major powers like Russia, China, the United Kingdom, and France are more confidently stepping in, pursuing their self-interests, and assuming more expansive political, economic, and security roles that either compete with or complement U.S. policies and interests.

Obama is right about one thing. We cannot continue to help police the Gulf as we did in the past. We have to invest in closer consultation and collaboration with NATO allies France and Britain, who have recently formulated plans to amplify their political-military presence in the region. Paired with strategic dialogue with adversaries such as Russia and China, that basic multilateral architecture would be more sustainable.

Obama’s top priority at the summit should be consulting with Gulf leaders on this new U.S. strategy. Riyadh is not the time and place to backslap or bemoan the promises made at last year’s Camp David summit. They must think beyond tactical wish lists and elevate the conversation to strategic levels. The Arab Gulf states might not show interest in increased and more formal British and French roles in Gulf security, and might even see this as another sign of a U.S. desire to reduce its regional footprint, but they will most probably appreciate the United States showing up with big ideas and new thinking.

Related: The Saudi Royal Family's Brittle Grip on Power Is Cracking

Having traveled extensively to the Gulf region in recent years and met with various senior officials to discuss relations with the United States and the West, I suspect that most Arab Gulf States would be quite receptive to a deeper involvement of the British and the French under American leadership. Indeed, a P3+1 model for Gulf security, comprising a forum of the United States, UK, France, and a Gulf party, is likely to be well received by most Arab Gulf capitals. Whether the Gulf would be represented by a leading state or the Gulf Cooperation Council, or GCC, would be up to the Arab Gulf States to decide. The UK and France most effectively could work on political-cultural dialogue, capacity building, training, counterterrorism, joint military exercises, and defense industrial modernization.

The sight of American, British, and French forces conducting joint exercises with Arab Gulf militaries would reassure Gulf partners and send a signal to post-sanctions Iran. Moreover, the group could more effectively and efficiently address Iran’s successful asymmetric warfare and the threats posed by terrorist organizations, including ISIS and al-Qaeda.

Russia and China would object. But it is worth emphasizing that they do not dispute that the U.S. has a key role in Gulf security and the Middle East more broadly. They have incentives to preserve and work within U.S. hegemony in the short and medium term, Russia’s intervention in Syria notwithstanding.

No U.S. official in the Pentagon, State Department, or elsewhere would like to see the United States’ strategic influence in the Gulf further wane. But our regional strategy needs a thorough update. The United States cannot indefinitely secure that region. As one senior U.S. military official recently put it privately, “the free-rider problem will not go away on its own.”

This article originally appeared on Defense One. Read more from Defense One:

Retaking A Booby-Trapped City, With US Help

What the US Gives Its Mideast Partners Isn’t Always What They Need