No matter how you look at it, even allowing for possible rounding downward, the unemployment rate, as of the end of August, was at a level the Federal Reserve Board’s Open Market Committee defines as “full employment.” The rate stands at 5.1 percent, a level it hasn’t touched since the spring of 2008. That’s right in the middle of the range of 5.0 to 5.2 percent that monetary policymakers had said would indicate that it’s time to start raising interest rates.

However, (how long has it been since there wasn’t at least one “however” appended to a report on positive jobs numbers?) other numbers reported this morning by the Bureau of Labor Statistics -- including the labor force participation rate, the number of people forced to work part-time even though they would prefer full-time work, and wage growth -- show little or no positive movement.

Related: Will the Fed Raise Rates in September? Look to the Markets for the Answer

BLS reported Tuesday that non-farm payroll workers in the U.S. had increased by 173,000 in August, a figure that was below economists’ expectations of 220,000. But that disappointment was softened by the fact that June’s job growth was revised upward by 14,000 and July’s by 30,000, making up almost all of the difference. If the trend continues, August’s numbers look likely to be revised upward also.

Indeed, PNC chief Economist Stuart Hoffman noted: “[T]he August preliminary payroll jobs number is notorious for understating the final revised data by a huge average of 78,000 jobs in the past three years, so there will be upward revisions to the 173,000 gain in the next two months.”

The seasonally adjusted civilian labor force participation rate clocked in at 62.6 percent for the third month in a row, while the employment-to-population ration also remained unchanged, at 59.4 percent. The percentage of the population that is actively participating in the labor force -- meaning that they are currently employed or are actively seeking a job -- remains at historic lows.

Even though the Baby Boom generation is again moving out of the workforce at a high rate, participation rates that low are seen by many as a sign that the unemployment rate may be artificially low, because workers who might otherwise be seeking jobs became discouraged by the lingering effects of the Great Recession and have permanently left the labor force.

Related: For Most Americans, Wages Aren’t Just Stagnating – They’re Falling

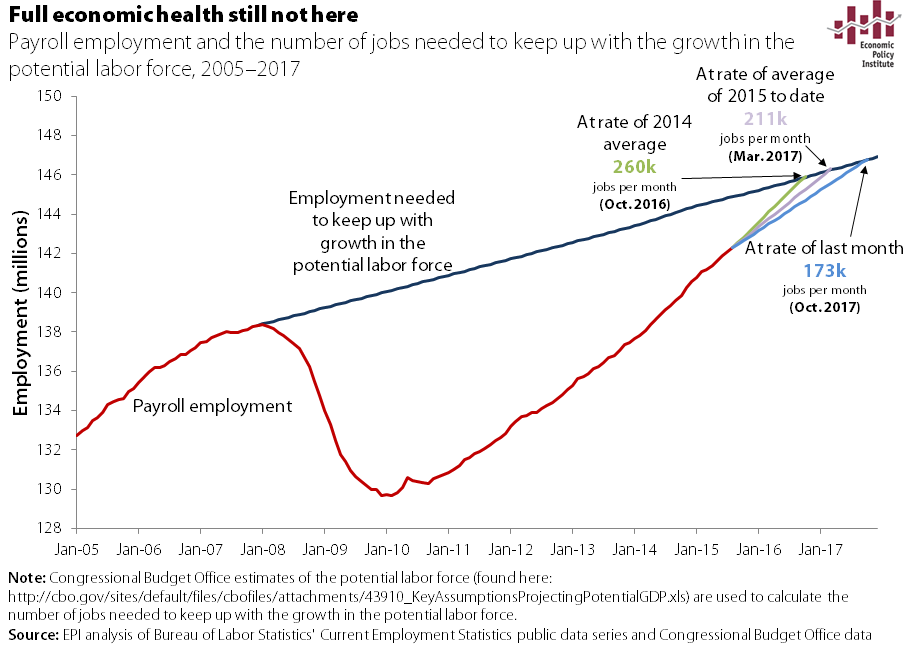

On Friday, the Economic Policy Institute in Washington updated its chart on the position of the jobs market vis-à-vis where it might have been expected to be without the effects of the recession. It suggests one reason why labor force participation might still be low: though things have improved dramatically, the country is still years away from recouping all the job lost between 2007 and 2009. At the average rate of job growth this year, the economy won’t get back to where it would have been without the recession until March 2017.

Hourly earnings continued to rise, but at the anemic pace of 2.2 percent per year, meaning that workers’ compensation is still not being significantly driven upward by tightening job markets. There was also no good news for people forced to work part time though they would prefer full-time employment. That number rose from 6.3 million to 6.5 million.

The net effect of the report on the pending decision by the Fed’s Open Markets Committee on when to begin raising interest rates above their current near-zero levels is uncertain. The FOMC has been very clear over the years that its decisions are data-dependent. However, that doesn’t offer a lot of guidance when the data itself is inconclusive.

Further complicating the question is the fact that Fed officials themselves have suggested that U.S. economic data may not be the only factor influencing a decision. Recent global stock market volatility and the potential for an overreaction to even a small increase to the already low rate might push the Fed to be a bit more dovish on rates when they meet later this month.

According to Paul Ashworth, chief U.S. economist for Capital Economics: “Even if the Fed doesn’t hike rates in September, it won’t leave rates at near-zero for much longer given that it either has (or is close to ) fulfilling the full employment part of its dual mandate. Fed officials are still fairly confident that shrinking slack means that inflation will rebound over the next year or two. Next year we expect core inflation to surprise on the upside, forcing the Fed into raising interest rates more aggressively than the markets currently anticipate.”