Picture this for a second: You’re whiling away the time at a train station, tapping away on your smartphone. Maybe you’re taking down friends and family in trivia. Maybe you’re crushing bits of candy together. Maybe you’re building a medieval empire. Whatever it is, you’re tapping away, building a barracks here or answering a trivia question there when you suddenly hit a wall. The power of your fingertips, which once forged civilizations, is suddenly gone, rendered ineffective by an icon of a clock with a disingenuous sad face.

It looks mournfully at you, its woeful stare somewhat countered by a tooltip letting you know that you have to wait two hours before you can do anything else, or pay $1.50 to keep going right now. Looking up at the station clock, you see that you still have 25 minutes before your train arrives. That’s too long. Way, way too long. Grimacing, hating yourself for what you’re about to do, you hammer your thumb on the glowing green button that reads “purchase.”

You’ve just agreed to a microtransaction.

Related: The App-Selling Power of Kate Upton’s Cleavage

In the world of gaming, pretty much everyone hates microtransactions (except, of course, for the companies that profit from them). They’re like taxes. Or Guy Fieri.

They’re purchases you make when timers and counters harass you, offering a chance to skip a forced time out for only 50 cents more. Or when you agree to download a 99-cent piece of meaningless extra content. Or buy a fictional in-game currency that only serves to obfuscate how much real money you’re actually blowing on virtual items.

If you’ve ever played a smartphone game, you’ve probably considered a microtransaction at some point.

Consumers hate microtransactions because for the most part, the game they’re trying to play was marked as free. Naturally, it’s frustrating to play an allegedly free game only to be harangued by popups and timers. Additionally, as we get more and more accustomed to the presence of these prompts, greedy publishers are packing them in to the point where it’s impossible to play some games past a certain point without laying down cold, hard cash.

Some developers also hate microtransactions. They shape the form of the game, create flaws in narrative and continuity, and for the most part cheapen the artistic credibility of their product.

Sadly for both parties, the free-to-play, microtransaction-supported model is going to be around for a while.

Related: Video Games Could Be Coming to Vegas Casinos

Let’s put it this way: The median cost for staffing a small development studio (say, around seven people) will usually clock in at about $500,000 a year, minimum. That’s for a skeleton team of moderately paid talent, and that’s not counting hefty expenses like office space, servers and computer equipment, or the programmers’ Mountain Dew. Throw all that into the mix and you’re looking at a million bucks a year, minimum.

No one has that kind of cash just laying around, so most new games these days are built on VC and other investors’ money. Obviously, venture capitalists have a vested interest in getting their money back and making a sizable chunk on top of that, so the games are structured in a manner that will reap the most profit.

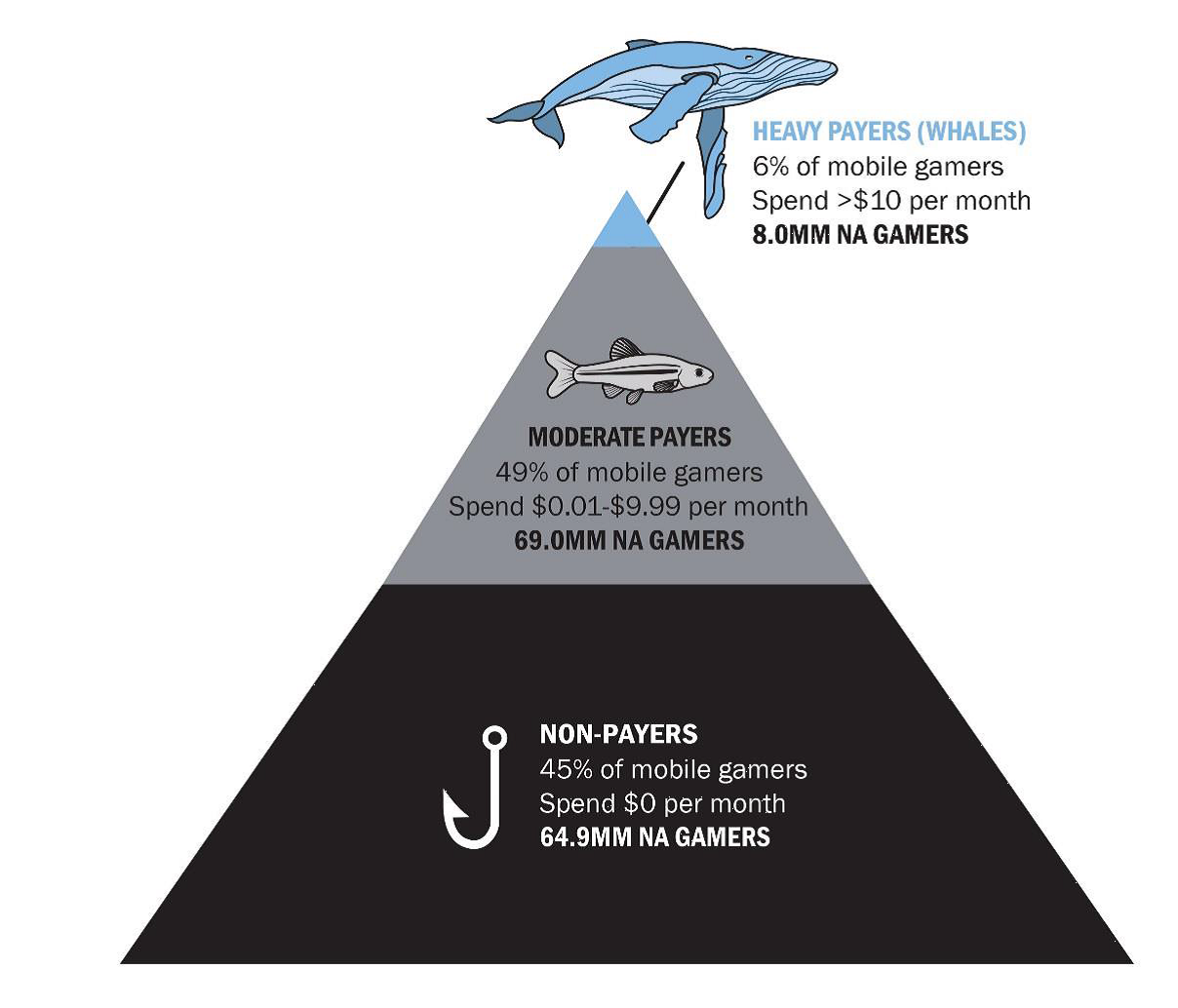

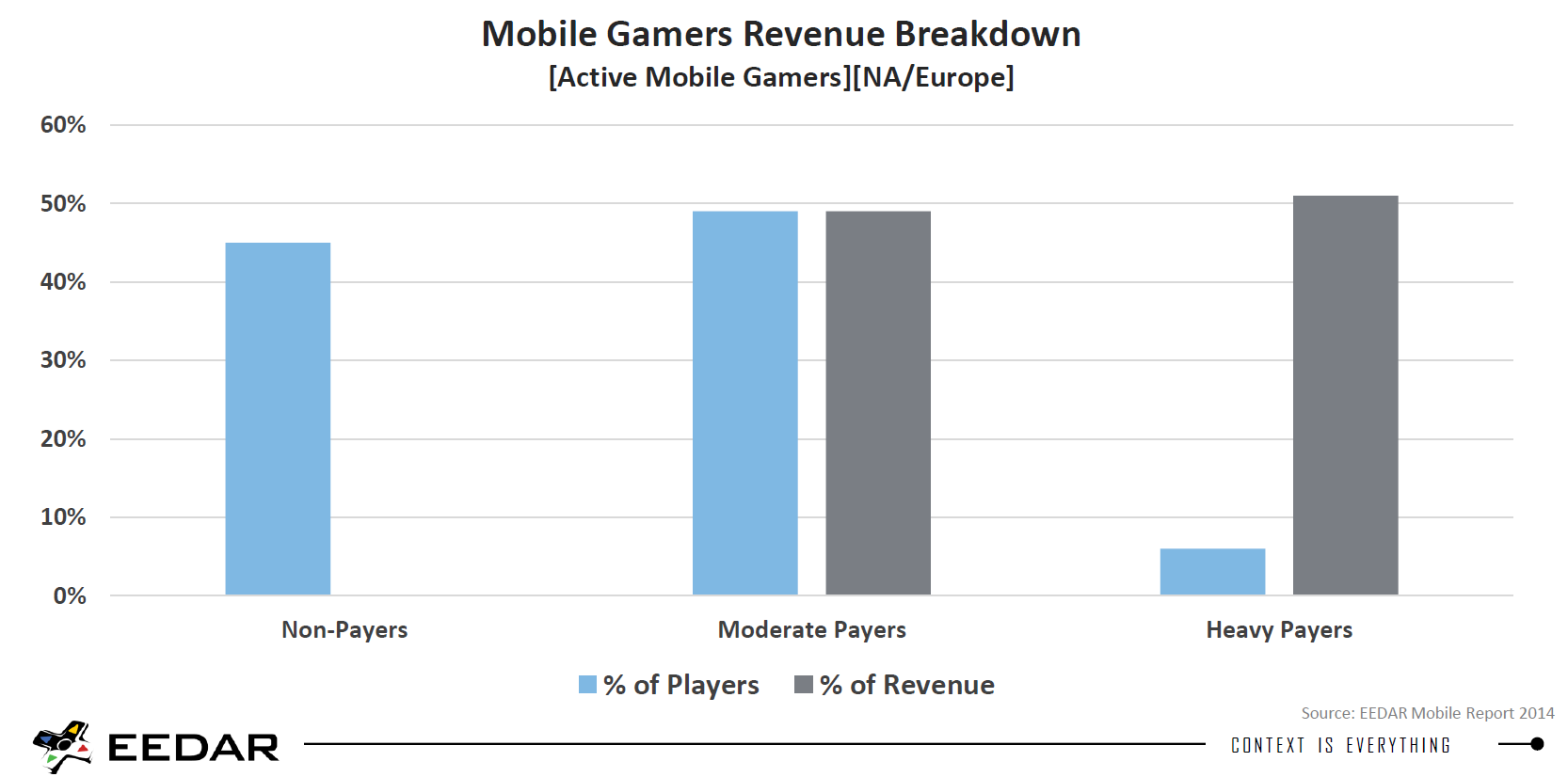

Currently, about 150 million people in the U.S. play mobile games regularly. Of the people who hop on to a free-to-play game, more than 45 percent won’t pay a dime, according to EEDAR, a video game consulting and research firm. They’ll give it a shot, muck about a bit, then either decide it’s not for them or hit a paywall they’re not willing to summit. Another 49 percent will throw a couple bucks into the game, but not enough to justify, say, taking out a second mortgage. The remaining 6 percent are the “whales,” an industry term for those that spend over $10 a month on a game — though many go way further than that.

Related: 21 Titles That Rocked the Video Game Industry

These fiscally irresponsible gamers are the magic ingredient keeping mobile games afloat. According to EEDAR, The vast majority of games — 92 percent — are now funded through in-app purchases, with the remaining 8 percent being premium games.

Source: EEDAR

Why not just charge a price for the game instead of charging for in-app purchases? Industry research shows a massive drop-off in consumer spending after the first two or three months on the market. And with so many apps nowadays containing multiplayer elements, requiring a team of moderators, developers, and support staff, the costs can quickly begin to outweigh the benefits.

Additionally, there’s the persistent risk of failure. Hundreds of thousands of games hit the Android and iOS app stores every year. Most are duds — insipid variations of Solitaire that deserve to sink to the peaty sludge of the App Store’s bottom tier. Some are almost certainly gems that suffered from a lack of a marketing budget or poor strategy. The point is that the games that succeeded on a purely premium model — the Flappy Birds and Monument Valleys — are the outliers in a field full of failures, winners in Apple’s Featured Apps lottery.

Source: EEDAR

Think again of that $500,000 price tag for staffing a development studio. Not even the most spend-happy of benefactors is going to want to field those odds. Thus, many premium games are created in basements and dorm rooms, whenever their developers get a free moment from their day jobs. This leads to more dross being pumped out, further ruining the chances for decent premium apps. For the best chance at success, in-app purchases are the only way to go.

So we can moan and whine as much as we like, but the fact of the matter is: Microtransactions are here to stay. That is, until we stop paying for them.

Top Reads from The Fiscal Times: