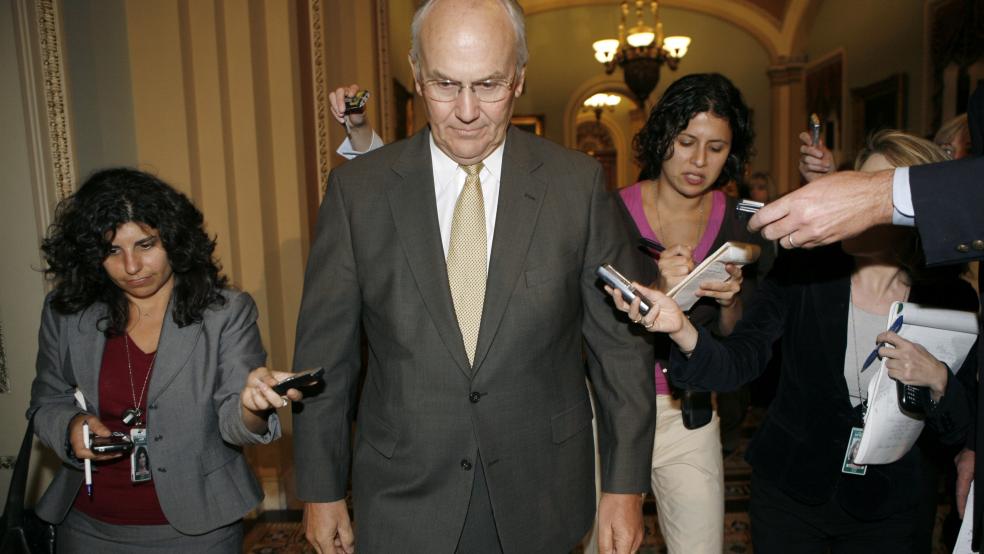

Back in June 2007, then-Republican senator Larry Craig of Idaho was arrested in a public restroom sex sting operation at the Minneapolis-St. Paul International Airport – a humiliating episode that shattered his reputation and eventually cost him his job.

Craig initially pled guilty to disturbing the peace and interfering with the privacy of another individual – a man who turned out to be a police decoy in a bathroom stall next to the one Craig was using. Craig was fined $500 and placed on probation for one year by a judge. Once the news got out, the embarrassed veteran senator announced he would resign that fall.

Related: Obscene Campaign Spending on 2014 Midterms Nears $4B

After further reflection, Craig decided to challenge his municipal court conviction and try to ride out the controversy on Capitol Hill, a decision that eventually led to a Senate Ethics Committee investigation and a costly legal battle.

Craig dipped into his personal campaign war chest for more than $197,500 to cover his mounting legal fees. Federal election law was once fairly lenient on how elected officials could use their campaign funds – both during and after their government service. But reforms passed in 1989 slammed the door on personal use of campaign funds, and the Federal Election Commission concluded that Craig had gone beyond the pale.

In November 2008, the FEC filed a complaint in federal court seeking to force Craig to pay back the $197,500.

Craig’s lawyers argued that the campaign money had been spent in “good faith,” based on guidance from counsel. But as Roll Call reported, a federal judge in Washington, D.C. last September ordered the Idaho Republican to pay a total of $242,535 to the Department of Treasury in restitution and fines. U.S. District Judge Amy Berman Jackson declared that Craig’s Senate campaign committee had functioned as “little more than an alter-ego for Senator Craig himself.”

Related: Big Returns on GOP Campaign Spending Investments

Now Craig is back in court, asking a federal appeals court to review the lower-court ruling, Roll Call reported on Wednesday. Apart from arguing that the former senator used his campaign funds for his legal defense on advice of counsel, Craig’s lawyers said the former senator has “endured severe professional and personal consequences” from the fall-out from the sex scandal.

Craig’s case is likely to get considerable attention from the political and legal community because of its potential for blowing a hole in the limitations on how politicians may spend from their campaign committees However, some campaign legal experts are skeptical that Craig will prevail.

“I read the district court decision and thought it was a very well analyzed decision,” said Lawrence Noble, senior counsel for The Campaign Legal Center and an expert on federal campaign finance law. “There’s no doubt that it’s a violation of the law in that you can’t use campaign funds for personal use. I think the FEC has been consistent on this.”

“And the thing he is complaining about now – the disgorging of the funds – I think is clearly within the court’s jurisdiction to order him to give the money to the U.S. Treasury, and not put back into his campaign.”

Politicians and federal lawmakers are not obliged to close out their campaign committees after an election or even after leaving office.

Related: The Shadowy World of ‘Dark Money’ Campaign Spending

According to the FEC, candidates or former officials may donate leftover money to charities and political parties, and make contributions directly to other political candidates, at a maximum of $2,000 per candidate per primary and general election. Politicians typically use excess funds to cover campaign debts. But they may also save extra campaign cash for future political campaigns.

As incredible as it may seem, retiring lawmakers were once allowed to keep excess campaign cash and spend it on a variety of personal expenses – such as vacations, houses and cars – until the passage of the Ethics Reform Act in 1989. Many members of Congress retired ahead of the effective date of that reform in order to hang onto their massive campaign war chests and use the money as they saw fit.

While some politicians choose to return their left-over campaign cash to donors, Noble said, others find it to be too time consuming and difficult in determining who should be repaid and who shouldn’t.

Related: How Dark Money Is Distorting Politics and Undermining Democracy

“In this particular case, I think the [judge’s] thought was he misused the funds and therefore he should lose all benefit from it,” Noble said in an interview. “And giving it back to the donors still gives him some benefit from the funds.”

In settling on the amount that Craig must pay to the Treasury, Judge Jackson noted that certain of Craig’s legal expenses related to media relations or responding to the Senate ethics inquiries could be partially or fully payable with campaign funds, based on legal precedent. But the lion’s share of Craig’s legal costs could not be covered by his campaign funds.

A growing number of lawmakers are leaving office with surpluses of $100,000 in their campaign war chest, according to a 2013 Center for Responsive Politics report. In the 1998 election cycle 18 former members of Congress retained that much campaign money. By 2012, that number almost tripled to 52 ex-lawmakers -- out of those, eight had more than $1 million remaining.

A large portion of those funds may be funneled to leadership PACs – which are covered by less stringent rules.

Top Reads from The Fiscal Times: