It’s long been an article of faith that the wheels of government bureaucracies turn more swiftly if they’re amply greased, whether in the U.S. or around the globe.

But apparently, that isn’t the case.

Related: The Downside of Government Regulation: Business Paralysis

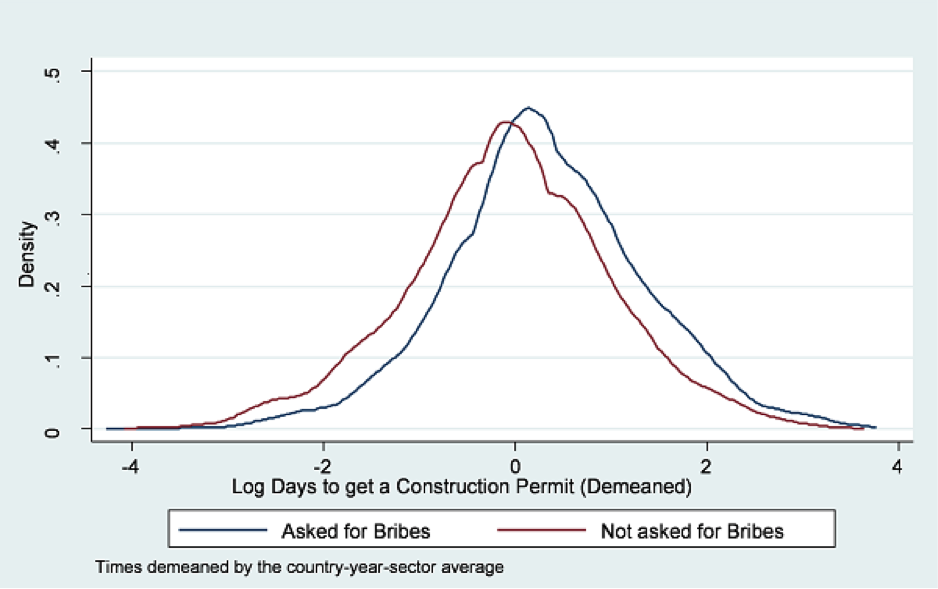

A recent international study touted on Friday by the Brookings Institution website tested this “grease the wheels” hypothesis and came up with an unexpected finding: Firms that were asked for bribes typically waited longer for their permits and licenses than other firms that were not approached.

Bob Rijkers, an economist with the World Bank, and three fellow researchers examined the relationship between demands for bribes and the time it takes applicants to comply with various regulatory requirements, such as obtaining construction permits and operating licenses.

The researchers used data that firms provided in response to the World Bank Enterprise Surveys of 107 countries. They set out to test the hypothesis that there is an inverse relationship between the frequency in which bribes are requested (and presumably granted) and the waiting time to obtain a permit or license.

They found that firms confronted with demands for side payments had to wait longer for action than those that were not asked for bribes. According to a blog post by Rijkers, statistical analysis suggests that such firms take about 1.5 times longer to get a construction permit, operating license, or electrical connection; and 1.2 to 1.4 times longer to clear customs, all else being equal.

Related: Americans More Concerned About Over-Regulation Than Economic Inequality

“Our econometric analysis rejects the idea that corruption is somehow more beneficial for firms who are more likely to pay, or in countries where regulations are more burdensome,” said Rijkers, who did the study with Caroline Freund, Mary Hallward-Driemeier and Varanya Chaubey. “Put simply, it rejects the hypothesis that corruption ‘greases the wheels.’”

The researchers’ findings are reassuring in one sense, in that the corruption that permeates many aspects of global government activities doesn’t always pay off. The report also hints at a larger point: that overly complex and time-consuming government regulations foster corruption by providing bureaucrats with increased opportunities to shake down applicants, many of whom are often more than willing to pay money under the table to expedite an application or review.

“My advice to countries that want to reduce corruption is get rid of unnecessary paperwork, simplify regulations and use technology as much as possible, because – for example – one-stop online registration forms don’t ask for bribes,” said Freund, a senior fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics in Washington, D.C.

The study has one shortcoming that makes sweeping generalizations more difficult to make, however. While the questionnaires used in the World Bank Enterprise Surveys asked firms whether they were asked to pay bribes, they were not asked whether they actually paid the bribes.

Freund says that few companies are willing to own up to having paid a bribe to do business – but they don’t mind saying whether someone tried to shake them down. Even so, she said, a lot of research has shown that data on the number of people asked to pay a bribe “is more highly associated with true levels of corruption than asking the question, ‘Did you pay a bribe?’”

Still, while it’s likely that many of those firms approached did indeed pay a bribe, many others may have balked at the request – and ended up being penalized by having to wait even longer than those who weren’t asked to pay a bribe. Rijkers is dismissive of any concerns about the limitations of the data.

“We rule out the possibility that the explanation for these delays is that firms that reported demands for bribes are somehow special … by comparing wait times incurred by the same firm across different applications,” he wrote in his blog.

Top Reads from The Fiscal Times: