With so many Americans turned off by Washington politicians and the record deluge of negative campaign ads, voter turnout for Tuesday’s mid-term election will probably be light again. But what if Americans had to vote or pay a fine, much as citizens of more than 30 other countries are required to do?

That would mean that millions of Americans could no longer come up with lame excuses for skipping an election, like getting their car detailed. And more state and local governments would be forced to extend early voting hours – or think twice before imposing ID requirements that may discourage some from going to the polls.

For years, William Galston of the Brookings Institution, a former adviser to President Bill Clinton, has been arguing the case for compulsory voting by Americans. And with the prospects of another light turnout today in this off-year election, Galston is back beating the drum for his plan.

Related: Analysts Predict GOP Will Pick Up at Least 6 Senate Seats

“Could I make an old-fashioned civic argument?” Galston said today on CNN. “You’re not required to do all that much as a citizen. It seems to me that asking citizens who enjoy all the rights and privileges of American citizenship to vote once every two years is not too much to ask.”

In fact it is too much to ask for some Americans who believe compulsory voting as a serious abridgement of their right not to vote if they choose – either out of indifference to the election or as a means of registering their strong disapproval of both political parties. Others say Galston should focus on people knowing and understanding the issues—and not voting blindly.

The Midterm Swoon

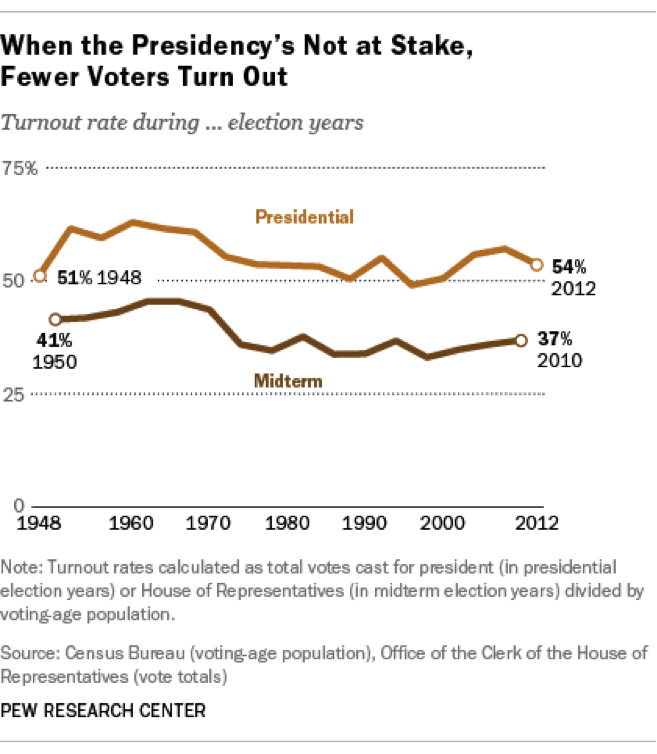

Voter turnout invariably drops in midterm elections, as it has done since the 1840s, according to a Pew Research Center study. For instance, 57.1 percent of the voting-age population cast ballots in the 2008 election – which was the highest level in 40 years – as Barack Obama made history as the first African-American to be elected president. Two years later, only 36.9 percent voted in the midterm election that put the GOP and its Tea Party allies in control of the House.

It’s safe to predict that today’s voter turnout will fall back to a 40 percent range, despite the political stakes for the country. From all indications, the Republicans will win back control of the Senate for the first time in almost a decade while adding to their already sizeable majority in the House. There is also a slew of governorships at stake, as well as more than 140 initiatives on ballots across the country ranging from the legalization of marijuana to raising the minimum wage and sentencing reforms.

With democratic freedoms an ever shrinking commodity around the world, the U.S. track record for election turnouts is something of a disgrace. Voter turnout has fluctuated in national elections to as high as 64 percent in 1960 when Democrat John F. Kennedy barely beat Republican Richard Nixon by a mere 112,827 votes to as low as 53 percent in 1996 when President Clinton defeated Republican challenger Bob Dole.

Related: Cruz, Paul Promise Very Different Futures If GOP Takes Senate

By contrast, voter turnout in Australia, Belgium and Chile hovered near 90 percent throughout the 2000s, while Sweden, Austria and Italy recorded turnout rates of nearly 80 percent, according to the Center for Voting and Democracy—all because of compulsory voting.

Galston, an expert on governance, believes the country has grown so politically and ideologically polarized that crucial decisions – including which party should be in charge of Congress and statehouses across the country– are being decided largely by voters on the far right and far left, but not by those who are more centrist in their thinking.

Those people staying home are generally more moderate, less attached to either party and less ideologically polarized, he notes. Without a much broader base of the electorate taking part in elections – especially in midterm that lack the excitement of a presidential contest, the campaigns are all about mobilizing “the most passionate voters.”

Related: Enthusiasm Gap Gives the GOP ‘Midterm Momentum’

There is a need, he says, to “broaden the political participation of less partisan citizens, who tend to be more weakly connected to the political system.” And that could come by enacting compulsory voting requirements in this country – an admittedly fanciful idea in an era of divided government and rampant distrust between the two major political parties.

“Near-universal voting raises the possibility that a bulge of casual voters, with little understanding of the issues and candidates, can muddy the waters by voting on non-substantive criteria, such as the order in which candidates’ names appear on the ballot,” he conceded. And yet, “The inevitable presence of some such ‘donkey voters,’ as they are called in Australia, does not appear to have badly marred the democratic process in that country,” he wrote.

Galston is the first to agree there are many reasons why compulsory voting would never fly in this country. Although the U.S. and Australia are both federal systems, the U.S. Constitution grants state governments far more extensive control over voting procedures. While it might not be flatly unconstitutional to mandate voting nationwide, Galston said, “It would surely chafe with American custom and provoke opposition in many states.”

Moreover, critics suggest that a drive for mandatory voting would founder in a country like the U.S. where party leaders would carefully gauge the relative benefits of vastly growing the participating electorate.

Related: Obscene Campaign Spending on 2014 Midterms Nears $4B

“Only governing parties with relatively under-mobilized electorates and a growing opposition find compulsory voting an attractive option,” wrote Gretchen Helmke and Bonnie Meguid, political scientists at the University of Rochester,

“Let’s be practical,” Galston said today on CNN. “This is not going to be instituted all at once as a national norm. What about if a half a dozen willing states step forward and experiment with it for a few election cycles. I think . . . it would have a dramatic effect that would appeal to the rest of the country.”

Top Reads from the Fiscal Times