As the nation digs itself out of the worst recession in 70 years, Americans are coming together to rebuild neighborhoods, raise money to save public services from brutal budget cuts, and make personal sacrifices for the benefit of others. The Fiscal Times will feature some of their stories in our series, The Path to Recovery.

In Paden City, West Virginia, a town of 2,513 residents and hub for glass marble manufacturing, on the banks of the Ohio River, there’s a small high school called Paden City. Most of the 159 students walk to school, and teachers know everyone’s name. But in 2008, a series of layoffs at nearby factories, including the Bayer Material Sciences plant, which eliminated 17 percent of its workforce and the Columbian Chemical Company which closed the local plant, caused the town’s population to dwindle. When residents got wind of a Wetzel County School District plan to shut down the high school due to budget constraints and declining enrollment, they mobilized and vowed to save the school.

As towns and cities across the country grapple with dwindling resources and declining government services, communities like Paden City are banding together to fight back. According to residents, Paden City High School is a major part of the local community with pep rallies and athletic events central to the town’s social life. Many of the high school’s alumni remain active in school-sponsored events, like the annual July 4th Alumni Weekend. “If we lose the school, we lose the town,” says Rodney McWilliams, a 1984 Paden City High graduate and president of the Paden City Foundation, a local trust fund that supports Paden city schools.

The town is split between two counties, and students have three schools from which to choose: Magnolia High School in Wetzel County, with 463 students, has a drama department and a plethora of extracurricular clubs; Tyler Consolidated High School in Tyler County, with 458 students, has a brand new campus; and then there’s Paden City High, the underdog. Principle Jay Salva says Paden City High’s main draw is the small class sizes: 15 students per class versus 25 per class over at Magnolia. Another draw is Paden City’s sports teams accept anyone who tries out. Most important, Paden City students consistently have high test scores, ranking fifth in the state last year. This year, all but one graduating senior is going on to college, according to Principle Salva.

“This high school is more than just a school.

It’s the heart of Paden City”

If the school were to close, Magnolia High School, five miles away, would absorb most of the students. But there is a rivalry between Paden City High and Magnolia dating back to the 1950s. Magnolia is located in the bigger town of New Martinsville, and typically receives more financial support from the county. Paden City, according to McWilliams, has always had to raise its own money for projects. He doesn’t think Paden City High students would be treated fairly at Magnolia.

In a survey by Challenge West Virginia, an advocacy group for small community schools, nine out of 10 parents said they would not send their students to Magnolia. “Send My Kids to Magnolia? Not in my lifetime,” says parent Lyle Barker. “I'll move first.” Tyler Consolidated High School is 30 miles away, but the majority of parents say they would rather send their kids there.

When the news was first announced that the school was slated to close, McWilliams and the Paden City Foundation started a group called Project Cornerstone to save the school. The group pored over budget documents and found that thanks to financial support from the community and the boosters club, the county was spending a mere 5 percent of its budget on Paden City High. Now all they had to do was prove to the county that the school could maintain or increase its enrollment numbers.

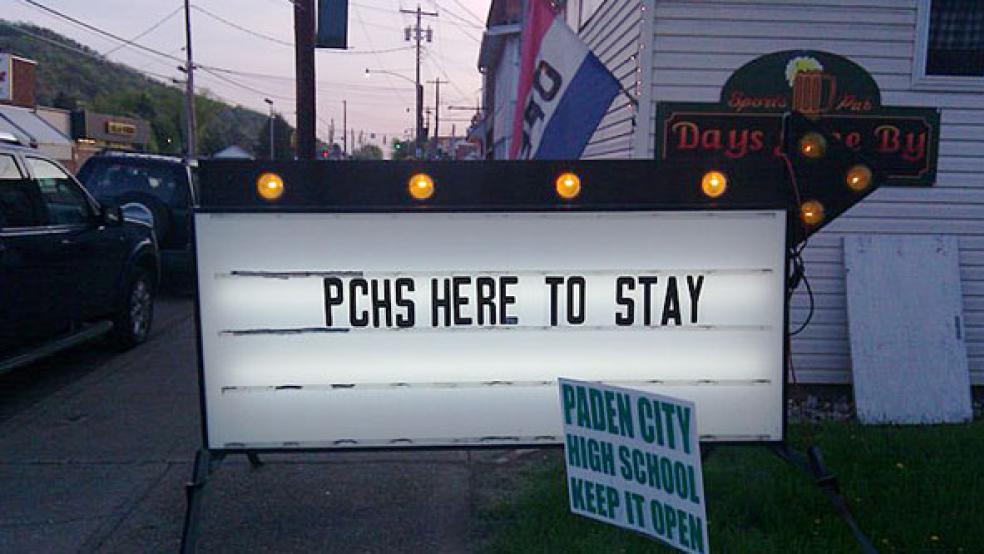

To do so, the group started an aggressive marketing campaign. McWilliams organized local fundraisers, raising $15,000; Alumni and community members wrote checks. They posted ads in the local newspaper and on billboards in nearby towns, aired radio ads that included voices from the students, and hung banners saying “Paden City High School. Open for All … Now and Always,” and staked over 250 yard signs. A Facebook group called “I Support Paden City High School” was created. McWilliams visited the state capital, and spoke with legislators about their cause.

On March 25, 2010, at the public hearing at the school’s gymnasium, more than 1,000 members of the community showed up in support, with police presence requested by the Board of Education in case things got rowdy. The band played the school fight song, and students spoke passionately about the benefits of attending a small school. The meeting lasted for nearly four hours as 35 former teachers, parents, alumni, business owners and students took the podium. One memorable speaker was exchange student Ziyi Xue, who spoke to the Board about how Paden City High School had accepted her as a member of the community.

They had to wait a month for the decision. McWilliams made one last-ditch effort, paying for a full-page ad in two local papers to explain the proceedings. “We weren’t 100 percent confident,” he said, “but we knew in our hearts we were on the right side of the argument.”

On April 19, 2010, the Wetzel County Board of Education unanimously voted to keep the school open, prompting many Paden City residents in the audience to burst into tears. When McWilliams and his crew returned to Paden City, a parade with local fire trucks, police cars and the ambulance was organized downtown. “We paraded through town, honking horns and waving signs and people came out of their front porches and hugged each other,” says McWilliams. “We met at the high school front lawn and some people gave speeches and we sang school songs. It makes you choke up when you tell it. It was like a movie. You can’t write scripts like this.”

At Paden City High School, things have already changed. Enrollment was up 5 percent in the fall and a handful of students who had transferred to a neighboring school have returned. Principle Salva says they recently added a drama club and plan to add a technology club and a hunting club next year. “This high school is more than just a school,” writes a former student on the school’s Facebook page. “It’s the heart of Paden City.”