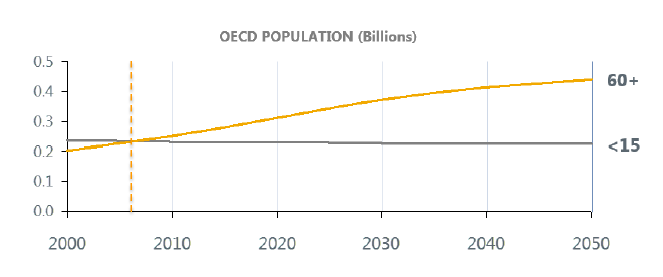

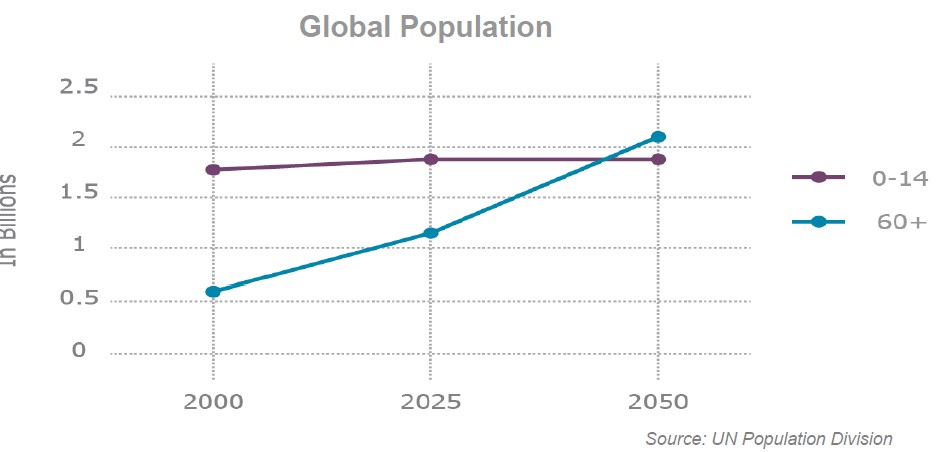

This past Saturday, October 1, we celebrated the International Day of Older Persons 2016. The world has reached a once unimaginable milestone in which long lives are becoming the norm. There are now roughly 1 billion people over the age of 60, and this number is expected to double by mid-century. Combined with the equally historic phenomenon of low birthrates, there are increasingly more old than young in the 35 nations of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, a trend that will accelerate globally over the next two decades.

The celebration comes a full 100 years after Germany began using 65 as the age of retirement, when a citizen would be eligible for health and social security benefits. This established what is now the iconic and universally accepted age of retirement – as well as the idea that people in their 60s are old.

Related: The American Retirement Crisis in 5 Charts

In a recent blog post, “Work Reimagined for the 21st Century – the Age of 65, 100 Years Later,” Peter Nicholson, vice president at Nestle Skin Health, writes: “In 1881 Otto von Bismarck, the conservative chancellor of Prussia, presented a radical idea to the Reichstag: government-run financial support for older members of society. In other words, health and financial benefits in retirement. While these benefits were originally proposed to begin at the age of 70, the age was lowered to 65 in 1916, when life expectancy was 50 for men and 54 for women.”

In other words, the fiscal and budget implications of a lower retirement age for Germany in 1916 were, to put it gently, manageable. Today, to put it not so gently, they are a fiscal nightmare.

What happens when everyone 65 and older is seen as one group? As unthinkable as it may be to put everyone from ages 10 to 40 together, this is what happens when we allow for such a simplistic demographic categorization. Perhaps it didn’t matter much when there were so few of us. But now it matters a lot.

So as we celebrate the International Day of Older Persons, perhaps it’s also a moment to begin redefining the demographic categories for the 60+ population. Such a shift could have huge implications. For example, as we develop a more realistic definition of what ‘old’ is, the number of people eligible for publicly subsidized health care benefits would likely decline, providing a much-needed shot in the arm to public finances. This would allow us to target the health needs of the truly older population suffering from serious and multiple chronic diseases such as Alzheimer’s. Publicly subsidized health benefits for a healthy, active and engaged 63-year-old ought to be distinguished from frail or cognitively challenged 87-year-old. And while everyone intuitively gets this, our current inclusion of 30 years of life in one demographic category leads to less than optimal results.

Related: The Retirement Cost That 80% of Americans Aren’t Ready For

Businesses around the planet are just now beginning to understand that a billion customers represent a market that cannot be ignored. But the nature of the goods and services that must be developed are somewhat confused due to the tendency to lump all those over age 60 together. Surely, there ought to be a clear distinction between a healthy 70-year-old and a sick 88-year-old.

So let’s join with the UN and others to celebrate the 2016 International Day of Older persons. But let’s also work toward an improved sense of what “old” is now as global society ages like never before.