For American investors, it looks all good: The Dow Jones Industrial Average remains near 18,000, biotech stocks are hot and the Nasdaq Composite is within a hair of its record high. U.S. GDP growth bounced back in the second quarter, advancing at a 2.3 percent annual clip as the job and housing markets continue to improve.

Yet a better indication of what's happening in world markets comes from the MSCI World (ex USA) Index, which is down more than 7 percent from its high set last summer. Or the iShares MSCI Emerging Markets (EEM), which is down 19 percent from last summer's highs. Or the DB Commodities Tracking Index Fund (DBC), which is down 43 percent.

Something is slipping. Factory orders here have expanded on a monthly basis only twice in the last 11 months. Excluding transportation, factory orders collapsed at a 7.5 percent annual rate in July, the worst since the maw of recession in 2009. With America's manufacturing sector looking shaky, the risk is that a global stalling pulls us down, too.

Related: Will the Rout in Junk Bonds and Commodities Crush Stocks, Too?

In Japan, despite a near 40 percent drop in the yen, industrial production is growing at just a 2 percent annual rate. Inflation is at just 0.4 percent year-over-year. The International Monetary Fund just warned Tokyo that its debts are unsustainable and set to reach 300 percent of GDP by 2030.

In China, the PMI manufacturing activity index dropped to 47.8 in July, down from 49.4 in June and below the neutral 50.0 mark for the fifth month in a row. Chinese factories are suffering their deepest contraction in activity since July 2013. Renewed declines in new work orders and new export orders has resulted in production being cut at its fastest rate since November 2011. Purchasing activity is falling at the fastest rate since January 2012.

The slowdown in the Middle Kingdom is affecting surrounding Asian economies. Singapore, Taiwan and South Korea are suffering industrial production contractions of 4.9 percent, 1.9 percent and 1.6 percent respectively on a year-over-year basis.

In Europe, despite aggressive efforts by the European Central Bank, lending activity remains tepid as core inflation — at a 1 percent annual rate — remains well below target.

The U.S. stock market is not an island onto itself. Nor can it ignore these forces for long.

Last week's results from Exxon Mobil (XOM) and Chevron (CVX) reminds us of the linkages between commodity prices, earnings growth and the overall stock market. Exxon reported a 52 percent drop in Q2 earnings on a net loss in U.S. upstream business. Chevron also reported weaker-than-expected results. CVX is down 34 percent from its high last summer. XOM is down 24 percent. The overall Energy Select Sector SPDR fund (XLE), representing the energy sector of the S&P 500, is down 31 percent.

Through last Friday, with 354 S&P 500 companies reporting, the blended earnings growth rate is expected to be -1.3 percent, according to FactSet data — the first outright decline in profitability since 2012 and the largest decline since 2009.

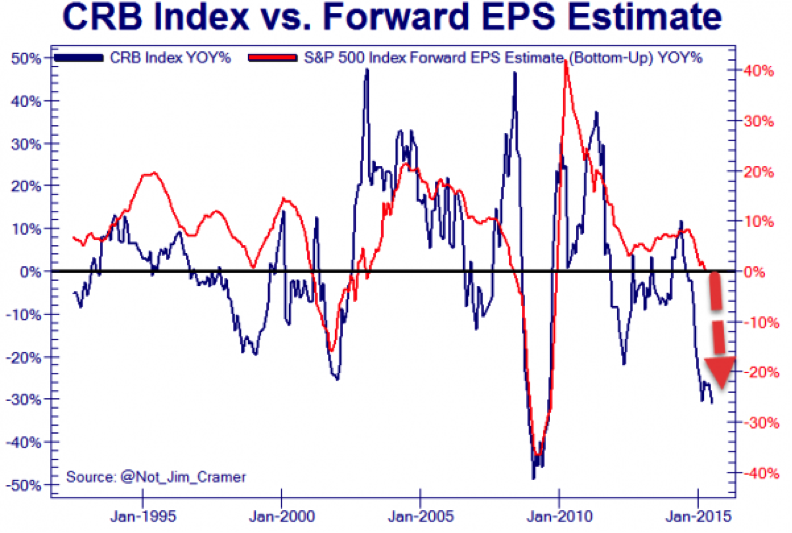

The chart above shows the close connection between commodity prices and S&P 500 forward earnings. The former is falling at a 30 percent annual rate while earnings growth has merely stalled. History suggests that shouldn't last, as the last two commodity price drops of this magnitude coincided with the last two recessions.

Not only are commodity prices impacting profitability, but the fading vitality of our trading partners is playing a role as well.

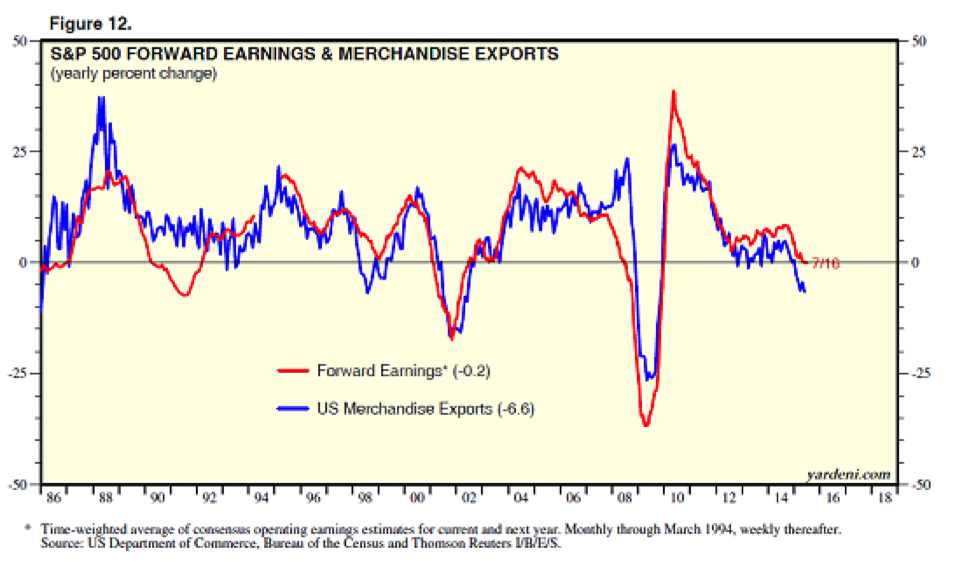

Ed Yardeni of Yardeni Research highlights the strong correlation between the growth in U.S. exports and the growth in S&P 500 forward earnings. The former is down 6.6 percent year-over-year through May while the latter is unchanged through the middle of July.

History again suggests the divergence will not last: The last two times U.S. export activity dropped to this extent, the global economy, including the U.S., was tipping into recession.

All of this is made all the more strange by the fact the slowdown is happening despite global central banks remaining in a full emergency stance — which is where they've more or less been since 2008. The Federal Reserve has made much of its intention to raise interest rates this year based on the situation in the labor market and an anticipated bounce in inflation (driven by rents and wages). But the Fed over the last eight years has also used higher stock prices as a tool to boost the economy via increased household wealth and purchasing power. Tightening now would magnify the drag on U.S. corporate profits (by increasing the cost of U.S. denominated debts, as I discussed last week) and the commodities crunch (via currency effects).

Yet not lifting rates now would undermine the Fed’s credibility and leave policymakers without ammunition should a global recession ensue. As Sept. 17 approaches, Janet Yellen and her colleagues face a dreadful decision: The devil or the deep blue sea.