Political writers often complain about something they call “the solutions chapter.” Whenever they write a book about a nagging societal problem, their editors always ask for a chapter at the end on how to fix it. And it’s typically the most banal chapter in the book, with shaky premises and suspect foundations. Because identifying problems is easy, but solutions are hard.

The solutions chapter problem usually leads to something Vox writer Matt Yglesias once termed the pundit’s fallacy. Matt describes it as pundits asserting that politicians will improve their popularity if they just adopt everything the pundit prefers substantively. This has advanced to every crisis that pops up in the news, all of which can be solved by a single policy the pundit has already favored for years. In this way, we can fix gun violence by marrying off single mothers, and resolve terrorism by ending abortion and homosexuality.

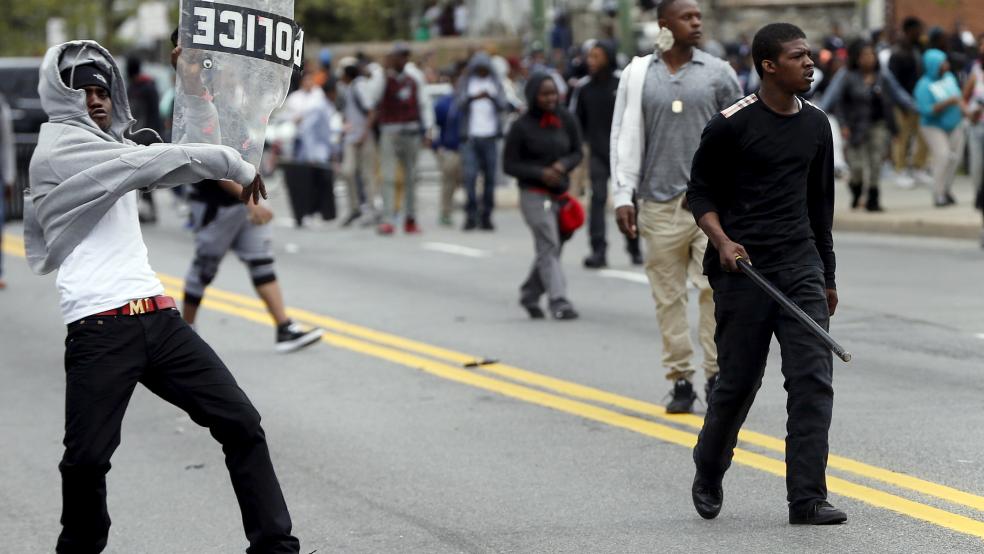

Related: How to Stop the Next Urban Race Riot? Ask a Republican

We’re seeing the pundit’s fallacy play out in earnest in the case of Baltimore, where protests in response to Freddie Gray’s death in police custody have played out all week. What Baltimore needs is school vouchers and charter schools, says Rudy Giuliani. Or it needs stronger father figures, argues Rand Paul. Or it needs conservative leaders in power, which was Rich Lowry’s suggestion. The fact that these line up perfectly with the views of these figures when they only thought of Baltimore as a place to get good crab cakes is purely coincidental.

This isn’t limited to one side of the political spectrum either. I could write a compelling column that the lack of economic opportunity and dwindling public investment in the inner city causes residents to lose hope, and that good-paying jobs would solve a lot of Baltimore’s ills. I could blame corporate flight, first to “right-to-work” states in the South and then outsourced abroad, which narrows opportunities for low- and middle-skill residents to join the middle class. I could call for a living wage for service-sector jobs to pull Baltimoreans out of poverty. I could argue, as Sara Mead did, that early childhood education in communities of color would give Baltimore’s kids a better chance to close the achievement gap.

I could say that the situation cries out for tighter restrictions on financial fraud, since foreclosures hollowed out Baltimore and lenders discriminated against its residents. I could even get esoteric and claim that Baltimore has been failed by the lack of filled vacancies on the Federal Reserve Board of Governors, whose monetary policy has failed to hit their inflation target for three years, leading to sluggish economic growth that trickles down to make at-risk communities more vulnerable.

Related: Here’s an Economic Agenda for Hillary Clinton

Not a single one of these theories relates to the actual touchstone for the civil disorder: the severing of the spine of a black man while under arrest. But there, too, there are plenty of “the solution happens to be the one I’ve always promoted” options, from ending the war on drugs and tough-on-crime lockup policies to removing burdens on cops who must deal with class divides and grinding poverty.

I feel I would be lying if I wrote a column highlighting a silver bullet to alleviate the woes of a downtrodden urban American city. Everyone believes their pet theory can have an impact on people’s lives, and they assuredly can at a macro level. But that doesn’t make them instantly applicable to the specifics of one place, and one group of people, and how they interact with one police department.

That’s particularly true in this place. Troubles in Baltimore date back to a time before the birth of virtually anyone currently living on Earth. Race riots in reaction to unjust deaths of young African-American men and police misconduct have a similarly long and ignominious history. That doesn’t make the associated problems completely intractable, but are cause for a little humility.

We do have a common set of facts to share about Baltimore, where the unemployment rate for black men aged 20 to 24 is 37 percent. We know that the city has paid out $5.7 million over the last few years in police brutality lawsuits. We know that a third of the people in Maryland prisons come from Baltimore. And we know about America’s history of racism and how it contributes to all of these factors.

But that doesn’t give us an instant roadmap to “the solutions chapter.” If it did, we would have installed such a plan after the Atlanta race riot of 1906 or the Chicago “Red Summer” riots of 1919 or Tulsa in 1921 or Rosewood in 1923 or Detroit in 1943 or Watts in 1965 (although it’s worth pointing out that the main consequence of that last one was the construction of a Lockheed Martin factory in the neighborhood, whose eventual shuttering in the late 1980s, along with other aerospace and automobile manufacturing plant closures at the time, deepened poverty in South L.A. before the Rodney King riots)

That there isn’t a ready-made solution for the twin conundrums of structural poverty and structural racism is what should really shock us, more than the images of Baltimore in crisis. For the past century, American leaders have allowed themselves to ignore places like Baltimore on the days when there aren’t any marches or protests. We have way too much documented history to let that continue. Urban neglect is a choice.

President Obama fell victim to the pundit’s fallacy too when he listed a number of possibilities in response to Baltimore that would have comfortably fit inside his Fiscal Year 2016 budget. But this part of what Obama said was correct: “If our society really wanted to solve the problem, we could… It’s just it would require everybody saying this is important.”

I don’t believe Obama always adhered to that principle: The White House Office of Urban Policy basically faded away. And poor people don’t vote enough, don’t give enough campaign contributions, and don’t hire enough lobbyists to make their importance felt in Washington. But it’s the correct sentiment, one that cannot be silenced by a position paper.

Top Reads from The Fiscal Times: