The wait is almost over.

It's been almost nine years since the Federal Reserve last raised its Federal Funds rate. Over that time, the monetary base has swelled from $812 billion to nearly $4 trillion. And now, with the unemployment rate down to 5.5 percent, the Federal Reserve's experiment with 0 percent interest rates is set to end soon.

The groundwork will be laid on Wednesday when the Fed issues its latest policy statement and summary of economic projections. At a post-meeting press conference, Fed Chair Janet Yellen will likely be looking to prepare the world for the first U.S. interest rate hike since 2006 — despite a powerful and destabilizing surge in the U.S. dollar, as well as tepid inflation measures.

Related: Why the ‘Smart Money’ Is Bailing Out of the Bull Market

To cut to the quick: Societe Generale's chief U.S. economist, Aneta Markowska, expects a rate hike in June and another at the end of the year, pushing the Fed's policy rate towards 0.75 percent. This is slightly less aggressive than where Fed policymakers pegged their median end-of-2015 interest rate prediction in December, suggesting a slight comedown from the Fed's “falling inflation isn't a problem” hawkishness.

This is well ahead of where the markets are: The Fed fund futures market is pricing in a single rate hike at the end of the year. This was always a little too optimistic; whispers more recently have focused around the September meeting as being the most likely candidate for liftoff.

The first step will be to remove the "patient" language from the Fed's policy statement on Wednesday — clearing the way for a rate hike at any time. Previously, Yellen had explained that this phrase meant no rate hikes for two meetings.

Related: Will Fed Rate Hikes Cost You in Higher Taxes?

This is all rather sudden for all those lulled into believing the Fed would never ever move aggressively to tighten monetary policy again. This is understandable. The Fed has been coddling markets for nearly a decade, has stated outright one of its policy goals was lifting asset prices, and has even seen former Chairman Ben Bernanke admit that interest rates wouldn't normalize in his lifetime.

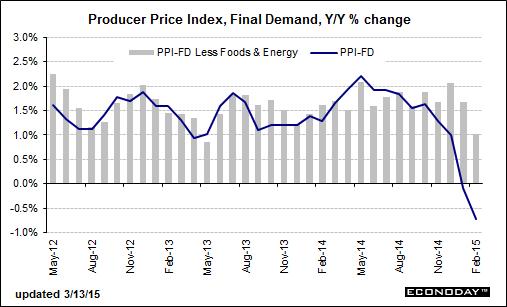

It also comes as a bit of a shock given the surge in the U.S. dollar (up 20 percent in the past year, for the fourth-largest move in modern history), the weakening of inflation measures (like the one shown above) and a recent weather-related stalling of U.S. GDP estimates in the wake of very soft data on factory orders and retail sales (the Atlanta Fed's GDPNow forecast for Q1 GDP growth has slowed to 0.6 percent).

The motivation for action has three parts:

First, before their self-imposed pre-meeting media blackout, Fed officials continued to strongly espouse a view that a recent softening of inflation measures was transitory — related to the weather and the drop in energy prices. Furthermore, the majority believed core measures of inflation as well as inflation expectations were stable and that headline inflation would gradually return to normal levels.

Related: America Is In Deflation. So What?

Second, this confidence is based on the drop in the unemployment rate to the upper end of the Fed's measure of "full employment" — suggesting we're on the cusp of a powerful surge of wage inflation. Outgoing Dallas Fed President Richard Fisher said on March 9 that should the pace of growth the U.S. economy enjoyed last year repeat (which included an outright contraction in activity in 1Q14 due to a severe winter) the year-end jobless rate could be around 4.5 percent.

Businesses are reporting they're having a tough time finding workers, are preparing for pay raises and expect profits to be pinched as a result. The number of job openings reported by the NFIB small business survey is at one of the highest levels in 40 years. As wages are pushed higher, so too should core inflation rise as increased purchasing power unleashes a wave of consumer demand, especially in housing.

Already, the gap between the unemployment rate and estimates of full employment — at 0.2 percent — is at or below the level that prevailed when the Fed started five of its last six rate tightening cycles since 1984.

Related: Is the Unemployment Rate Just a ‘Big Lie’?

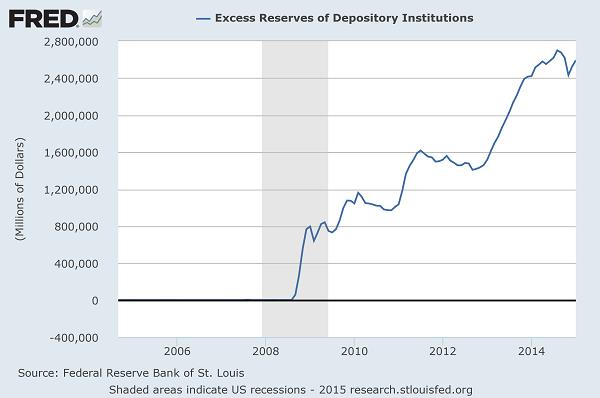

The third reason, and the one highlighted by Markowska, is technical in nature. The Fed has never been in this position before. It's never held interest rates this low for this long. And it's never tried to push rates higher after flooding the financial system with three rounds of bond-buying stimulus and a maturity-extending "Operation Twist" program.

The tools it plans to use to force the price of money higher — at a time when the banking system is holding $2.4 trillion in idle cash — haven't been tested at scale. They are a mix of reverse repurchase agreements and term deposit facilities, all designed to drain liquidity out of the financial system.

There are also risks of adverse reactions in the bond market, where trading liquidity (down about 40 percent from 2008 levels) has dropped to a point where changes in rates could have an outsized impact on bond pricing. The Institute of International Finance, a global association of banks, warned of the "illusion of liquidity" in these markets back in September noting that adjustments to the end of 0 percent interest rates could be "disorderly."

The longer the Fed waits, the more difficult the eventual adjustment will be.

Related: Americans Are About to Get a Nice Fat Pay Raise

After June, in a nod to the Fed's stated data-dependency and desire to avoid a market shock, Markowska believes Yellen is likely to hold off on any further rate hikes until inflation stabilizes, job growth continues, GDP growth bounces back and the dollar's rise remains relatively controlled.

It remains to be seen whether a pause after the first hike will be enough to calm the liquidity junkies on Wall Street, who've grown dependent on the Fed's monetary morphine and are loath to admit it's going to end. The needle is coming out as the IV drip is pinched off. One cannot overemphasize how big of a deal this is for everything from dollar-denominated loans in China to corporate bond yields to debt-fueled corporate stock buyback programs.

Whatever comes, Wednesday will likely mark the beginning.

Top Reads from The Fiscal Times: