Despite another steady surge of payrolls, and a larger-than-expected drop in the unemployment rate to 5.6 percent, stocks reacted negatively to Friday's jobs report. For many, that was a bit of a head scratcher.

The obvious answer was that investors were disappointed in the report's soft reading on wage gains. Another interpretation is that the decline in the unemployment rate reflects a quicker-than-anticipated tightening of the labor market, one that will put pressure on the Federal Reserve to raise interest rates sooner and more aggressively than the market previously expected.

Related: Why a Booming Job Market Hasn’t Led to a Booming Housing Market

Indeed, at 5.6 percent the unemployment rate is near the Fed's 5.2 percent to 5.5 percent estimate of long-run unemployment. It's also very near the Congressional Budget Office's estimate of the "non-accelerating inflation rate of unemployment" — also known as the natural rate of unemployment — at 5.5 percent.

At the current pace, the unemployment rate will drop to 5 percent by this summer, which would represent the level the Fed expected at the end of 2016. And according to Deutsche Bank, the unemployment rate is on track to end the year at 4.7 percent, or possibly lower, as the pool of the long-term unemployed dries up.

That means meaningful wage inflation should start materializing soon, something that could crimp corporate earnings as labor costs rise and force the Fed to hike rates. The combination of higher credit costs and a slowdown in earnings growth isn't an attractive one; thus, Friday's selloff and its continuation on Monday.

Related: Why Oil Prices Are Headed Below $35 a Barrel

For now, the Fed can afford to wait because measures of wage inflation remain moribund: Average hourly earnings in December actually dropped 0.2 percent from November. (For what it's worth, analysts are casting this as an outlier possibly driven by seasonal factors or maybe a delay in giving raises ahead of minimum wage hikes in a number of states.)

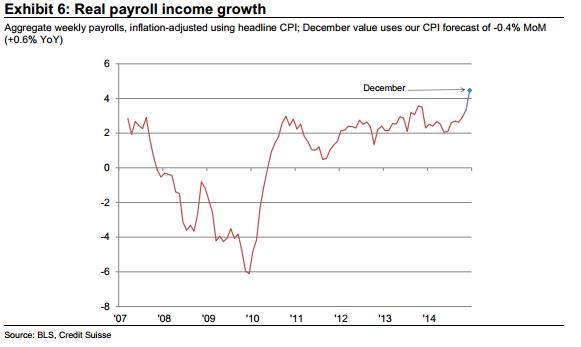

This misses an important point, though: Inflation-adjusted take home pay, which accounts for the cost of living, has just started surging in a big way. If that continues, which looks likely, middle-class Americans could see a lift to purchasing power that they haven't seen in the recovery to date.

Analysts at Credit Suisse led by Jay Feldman broke down the numbers in terms of "real payroll income growth" — which captures the impact of jobs created, hours worked and hourly wages — and were pleased with what they're seeing: Their estimate of real payroll income is expanding at a 4.5 percent annual clip. That's the strongest rate of growth of the expansion to date, thanks largely to the tailwind provided by lower energy prices, with wholesale gasoline futures down nearly 60 percent from their highs last summer.

Related: Why Vanguard Won 2014, and What That Means for 2015

Moreover, given the oddness of December's wage decline, the team at Credit Suisse is looking for a quick bounce back when January's numbers are released early next month. If so, there could be negative consequences for Fed policy and corporate profits as we head into the middle of 2015.

Top Reads from The Fiscal Times:

- Why Democrats Are Pushing a $1.2 Trillion Redistribution of Wealth

- Can the U.S. Boom While the World Busts?

- The 10 Most Livable Cities in America