How much are you worth as a worker?

That’s an easy question for the 55 employees at WhatsApp to answer right now. In the wake of the bombshell news that Facebook not only acquired the tiny messaging service company at the anything-but-tiny price of $19 billion, pundits and observers of all kinds have been crunching the numbers. It turns out that at that price, each employee is worth some $345 million.

The tradition, of course, is to value a company using all kinds of other metrics. For publicly traded firms, the price/earnings ratio is a traditional measurement, with others including price to cash flow, revenue or book value. When it comes to privately traded companies, you have to get a little more creative (unless you’re an insider), which is why the “per employee” number has made such a splash, along with the $42 per WhatsApp user price tag.

Related: Mark Zuckerberg Says $19B for WhatsApp Is a Bargain. Is He Right?

The traditional valuation metrics make sense from an investor’s perspective. After all, when a shareholder invests, he’s not acquiring a bunch of employees but the right to profit from an increase in the revenues and profits that those employees generate. The employees themselves are simply a means to an end.

Still, putting tradition to one side for a moment and focusing instead on the market value of employees can also be informative, in a completely different way. That’s particularly true in light of the longstanding debate over what kind of minimum wage (state or federal) is appropriate these days.

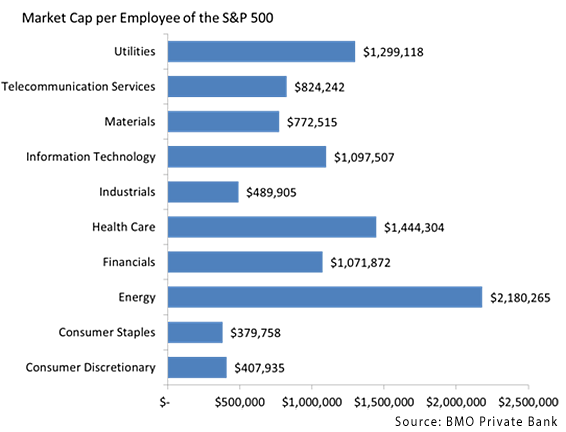

News of those ultra-valuable WhatsApp employees sent Jack Ablin, Chicago-based chief investment officer at BMO Private Bank, to do some number crunching of his own. It turns out that Facebook’s own employees are apparently seen by investors as immensely valuable, although at about only a tenth the level as those of WhatsApp.

The energy, health care, utilities and tech sectors all fare well in the market cap-to-employee analysis, but energy and utilities are both capital-intensive industries, Ablin notes. Similarly, some companies, particularly some real estate investment trusts, have very large asset bases relative to the number of their employees. At Healthcare Property Investors (NYSE: HCP), for example, each employee’s contribution to future profits might be valued at $111 million based on the number of employees and the REIT’s market capitalization.

The takeaway from all that: tech, along with health care, is where you can best see the value of employees to a company’s stock. “The truly elite thinkers among today’s students would be well advised to pursue career paths in those fields if they want to make sure they are on the advantaged side of the income equality divide,” Ablin suggests.

At the other end of the spectrum, let’s ponder Wal-Mart Stores (NYSE: WMT), which has about 2.2 million employees worldwide and has a market capitalization around $240 billion. Collectively, the efforts of those employees generated net income of $4.43 billion in the just-ended fiscal year, up from $3.78 billion the previous year. Based on the company’s valuation, the market values each employee at about $109,000, on average. Now, consider that perhaps 900,000 of those employees in the United States alone make less than $25,000 a year, according to the company’s own admission.

No, I’m not trying to cram together apples and oranges by suggesting that employees should collect salaries that reflect the value that investors ascribe to their collective efforts. Companies — unless they are deliberately established as partnerships or worker-owned co-operatives — are set up to act in the best interests of their investors, not their employees. As interpreted by Wal-Mart and other businesses whose jobs require significantly less skill and education than those at companies like Facebook or Google, that has meant wages that often fall just above — and sometimes even below — the poverty line.

Still, some high-level numbers show that how focus on rewarding investors has affected workers. If you go back 30 years, corporate profits bounced around at a level that was about 7 percent to 8 percent of the GDP of the United States; employee compensation was between 56 percent and 57 percent of GDP. Today, those figures are closer to 12 percent and 52 percent, respectively. In other words, a significantly greater chunk of the country’s economy is accounted for by corporate profits, while paychecks make up a smaller portion. And that 52 percent is the lowest number on record in more than half a century. The 12 percent? Well, that matches the highest level recorded since 1949.

Add to that the fact that the minimum wage, adjusted for inflation, has actually fallen by more than $3 an hour — or 30 percent — since it peaked in 1968. Today’s $7.25 an hour will buy you about what $1.60 bought you back in the year that Martin Luther King, Jr. and Robert Kennedy were assassinated. More of Ablin’s number-crunching earlier this week brought him to the conclusion that based solely on inflation, today’s minimum wage should be above $9 an hour. If you throw productivity into the mix — reflecting the increased value that employees are generating for their companies, a figure that shows up in both the GDP numbers and in the Wal-Mart profit statement — the figure should be north of $15 an hour.

Related: CBO Says Minimum Wage Hike Would Cost 500,000 Jobs

Now, that’s an aggregate number, of course. Clearly, not all companies in all industries will be able to afford to fork over that much money, at least as things stand today. But given that roughly two-thirds of economic activity in the United States is driven by consumer spending, surely if companies like Wal-Mart — which clearly can afford to boost wages — pay employees at a higher rate, that will show up in higher rates of consumer spending.

Perhaps Wal-Mart employees will begin buying their groceries at the store rather than relying on food drives and food banks? Perhaps a local restaurant or a day care service will find that there is more demand for their business, and either volume or price increases will help offset their own higher costs?

Some companies are already thinking about this state of affairs in a new way. Costco, for instance, has long since made a strategic decision to use some of its profits to finance higher employee salaries. The tradeoff for those higher costs? Higher productivity — and potentially higher customer satisfaction. Now the Gap is following the same path, announcing its plan to boost the minimum wage it pays to $9 an hour this year and $10 by the end of 2015.

Of course, this isn’t just “be nice to your underpaid workers” week in the retail industry. Gap clearly feels that by paying more, it’s more likely to attract the workers it needs: those able to guide and advise customers, not just stack shelves.

Related: 1,400 Real World Minimum Wage Increases Show No Impact on Employment

Employees at companies like McDonald’s and Wal-Mart are least likely to have other, more attractive options. Even so, there’s a solid business case to be made in favor of executives at both companies placing a higher value on their employees, as reflected in their wages. Motivated and happy employees generate good PR for their company, not lousy news headlines. They generate sales. Their spending keeps other businesses going, whose employees can in turn now pick up lunch at McDonald’s twice a week instead of only once.

That would, however, require a big shift in the way companies think about profits. If every dime of additional productivity is destined for the shareholders of a company, without even a penny being directed toward its workers (who generate those productivity gains), well, little will change regardless of what dollar number is established as a minimum wage.

Top Reads from The Fiscal Times: