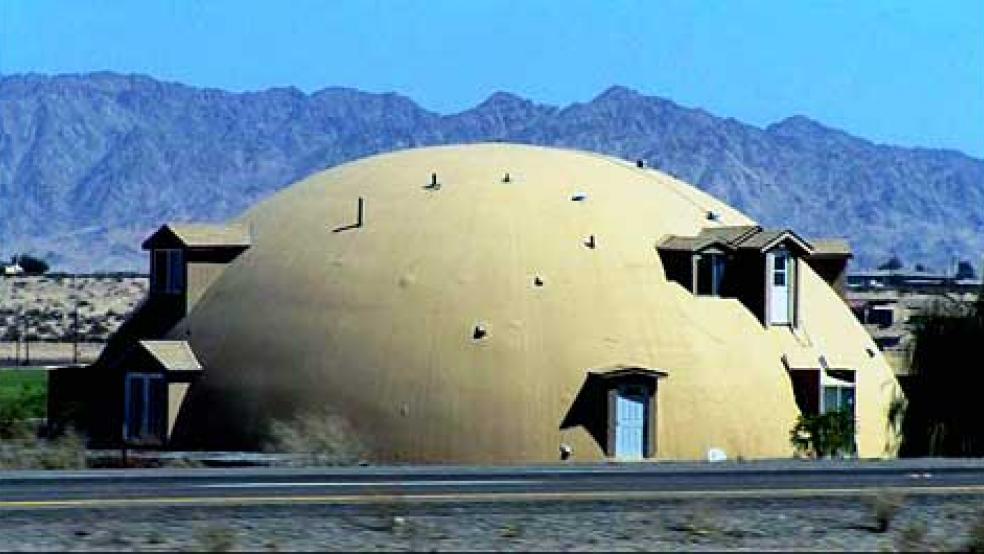

Over the past decade, the world has watched in horror as hurricanes, floods, tornadoes, fires, mudslides, tsunamis and most recently, one of the largest typhoons on record, caused death and destruction in epic numbers. With meteorologists predicting even more intense storms in the future, some homeowners are finding a simple yet ingenious way to minimize their vulnerability: building a dome home.

The domes' balanced shape is self-supporting and strong enough to withstand the force of an EF5 tornado, a monster hurricane or a powerful earthquake. Dome buildings made of concrete can deflect falling buildings and flying debris, even airborne trees and cars. Plus, the roof won't blow off.

Related: 10 Devastating Disasters of the Last Decade

"People feel safer in a dome," says design engineer and Texas resident Nanette South Clark. "Domes have a double curvature like an egg so they're very strong. They're the buildings of the future."

Clark, who helped design space shuttle launch systems, grew up in a dome home herself. It was designed by her father, David South, who was inspired by the intricate balance and symmetry of Buckminster Fuller's geodesic spheres. South created his "Monolithic Dome" as a round, freestanding structure that could be economically built to serve as protection against natural disasters and a unique living space.

"This is an answer," insists Clark's husband Gary, vice president of Monolithic sales and marketing. "It's the strongest disaster-preventative shape that can be built for the dollar."

In fact, today the Monolithic Dome Institute has taken its vision globally to build domes for residential and commercial use. Concentrating on areas prone to natural disasters, the company is currently aiming to build 20 dome shelters in Birmingham, Ala., a city devastated by tornadoes in April 2011. In 2006, Monolithic built 71 dome homes—an entire village—in Indonesia after the mass destruction caused by an earthquake.

The Federal Emergency Management Agency agrees that domes can play a part in disaster preparedness. In 2012, FEMA spent millions of dollars to build dome shelters in Texas communities that had been hard hit by tornadoes. In May, a photo on the FEMA website showed how well a dome fared compared with a conventional building after the EF5 tornado in Moore, Okla.

The problem, say dome advocates, is that meteorologists are predicting even more violent weather systems and domes are still a rarity. The last decade has seen a tenfold increase in major earthquakes worldwide, according to a recent United States Geological Survey, as well as some of the deadliest hurricanes and tornadoes on record. In 2012 alone, 251 people died in the U.S. in weather-related disasters that cost $104 billion.

Related: State Disaster Declarations: Are They Non-Partisan?

MIT scientist Kerry Emanuel, one of the world's top experts on hurricanes, published a paper this year predicting that the world will see even more intense tropical storms in the future, in combination with rising sea levels. Emanuel's 2005 article published in the international science journal Nature foreshadowed 2013's Typhoon Haiyan in the Philippines, (death toll 6,000) and 2008's Cyclone Nargis in Myanmar (death toll 138,000).

"Hurricane intensity should increase with increasing global mean temperatures. ... This trend is due to both longer storm lifetimes and greater storm intensities. ... My results suggest that future warming may lead to an upward trend in tropical cyclone destructive potential, and—taking into account an increasing coastal population—a substantial increase in hurricane-related losses in the twenty-first century," he wrote in the Nature article.

"In the next 50 years, we do expect to see an increased incidence in the most intense hurricanes," Emanuel told CNBC. "If I were living in the Philippines, I would certainly build stronger buildings and put a lot emphasis on saving lives. I'd certainly build hospitals and storm shelters much stronger than I might have built them before.

"Whether it's worth the money to build ordinary homes and buildings stronger is an economic decision; even with global warming, another storm like that might not happen in another hundred years. But I would say that, in a broader sense, building alternative structures that can withstand intense storms is something that urban planners certainly have to think about."

According to Gary Clark, a Monolithic Dome currently costs between $125 and $135 a square foot. Not accounting for architectural enhancements, that figure, $125,000-$135,000, is on par with the average cost of a 1,000-square-foot home in Texas. "Dome homes are probably about the cost of a standard home, maybe slightly more. But we're really green—that's where we shine. Your energy costs will basically be 50-75 percent less than in a conventional house."

So with all the advantages of dome homes, why are they so rare? "The shape is the problem," explains South Carolina architect Peter von Ahn. "Domes are very efficient and work well, but the majority of people don't like them. They don't fit people's preconceived notion of what a house should look like."

Related: 5 Reasons the Luxury Real Estate Market Is Booming

Often playfully dubbed "ball houses," "bubbles" or "igloos," domes can produce a variety of reactions from passersby, from delight to disgust to just plain old confusion. Sotheby's International Realty is currently selling a rainbow-colored, multidomed structure in Sedona, Ariz., that is unique, to say the least. Resembling a space-age cartoon dwelling more than a traditional home, it's on the market for a little more than a million dollars.

"It's not for everybody," admits selling agent Ken Robertson. "It takes someone with imagination and creativity to appreciate this home. It's almost like a fantasy home."

Interestingly, even survivors of major storms often say they would not consider moving into something as "weird" as a dome home, regardless of its protective qualities. "It would be a real stretch to consider that," says Clark Crabill, a 67-year-old retiree from Cincinnati. "It would be so extreme."

Though his home was decimated by a tornado 14 years ago, ("it took less than 10 seconds to pop the house; it was like an explosion") Crabill says he would never consider buying a dome home. In fact, his reaction to the tornado was to search for the blueprints of his original home and rebuild it exactly like the first.

Crabill acknowledges that he lives in the wide swath of country known as "Tornado Alley," but is convinced, "The probability of a tornado happening here again is low."

Clark's daughter Carrie says she still feels emotional when she thinks about the early morning of April 9, 1999. "I was thrown out of bed onto the floor," she recalls. "I looked up and saw the sky. My sister was found in the neighbor's yard."

Though her family survived, four people died in that tornado. Carrie says she has never truly felt safe since that day. "Our home was all gone, except for the basement and the foundation," she says. "Your sense of home and where you belong is taken from you. I will never not be aware of a storm again. Regardless of where I am, I'm always aware of the weather."

This article originally appeared in CNBC.

Read more at CNBC:

New home sales dip after Southern surge

Market is ignoring the bubble in housing

Wait-and-see economy slows recovery