The public school in Campo, Colorado, hasn’t required all its students to come to class on Fridays for nearly two decades. The 44-student district dropped a weekday to boost attendance and better attract teachers to a town so deep in farm country that the nearest grocery store is more than 20 miles away.

“I think the four-day week helped us, initially, in recruiting teachers,” the superintendent, Nikki Johnson, said. “Now that so many districts are on four-day, that’s not much of an incentive.”

No national database tracks the number of public schools that cram instructional hours into four days. But the schedule — long popular in rural Western communities — is becoming more common elsewhere as school leaders search for ways to both attract teachers and save money.

In Oklahoma, for instance, where teachers recently staged a walkout to demand more school funding, cash-strapped districts have been using four-day weeks to cope with a teacher shortage and state budget cuts. Last school year, 97 districts of 513 ran on the compressed schedule, nearly twice as many as the previous year.

Shorter school weeks are generally popular among families, students and teachers, and many school districts say the change saves money and makes it easier to recruit teachers. But the research is inconclusive: Shorter school weeks save only a little, according to education policy researchers. The impact on staffing hasn’t been well studied, and results are mixed on whether cramming a week’s worth of learning into four days helps or hurts students’ learning.

And the changes aren’t universally popular. Critics say four-day weeks hurt working families who have to scramble to find child care and could prevent children from accessing free or low-cost meals five days a week. A recent study found that juvenile crime rates were higher in parts of Colorado where schools didn’t meet on Fridays.

Still, over half of Colorado’s public school districts have permission from the state to compress their schedule. Most such districts are small and rural, but that’s changing. A suburban district near Denver and an urban district in Pueblo have recently grabbed headlines by announcing that they plan to switch to four-day weeks in the fall.

Little is known about how urban districts will adapt to the new schedule. But rural districts that make the switch rarely go back, said Georgia Heyward, a research analyst for the Center on Reinventing Public Education at the University of Washington Bothell who has studied four-day school weeks in rural areas.

Once parents, students and teachers adjust to the new schedule, they tend to like it — and the community adjusts around it. “Once a couple of the districts start to go to the four-day week, then there’s pressure, not only not to go back, but for neighboring districts to adopt the schedule as well,” Heyward said.

More Districts Drop a School Day

In some districts, schools have been meeting four days a week for decades. The schedule gained fresh popularity in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis, when districts responded to budget cuts by shedding a day.

Today school districts in parts of 22 states use a four-day week, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures. For districts to do so, states need to enact legislation that allows schools to count instructional time by the hour, rather than by the week. States west of the Mississippi are more likely to have schools on a four-day schedule.

The state legislatures group estimates that close to 300 school districts nationwide are using the shorter weeks, but Heyward puts the number higher, at 470 districts or more. There are more than 13,500 U.S. school districts.

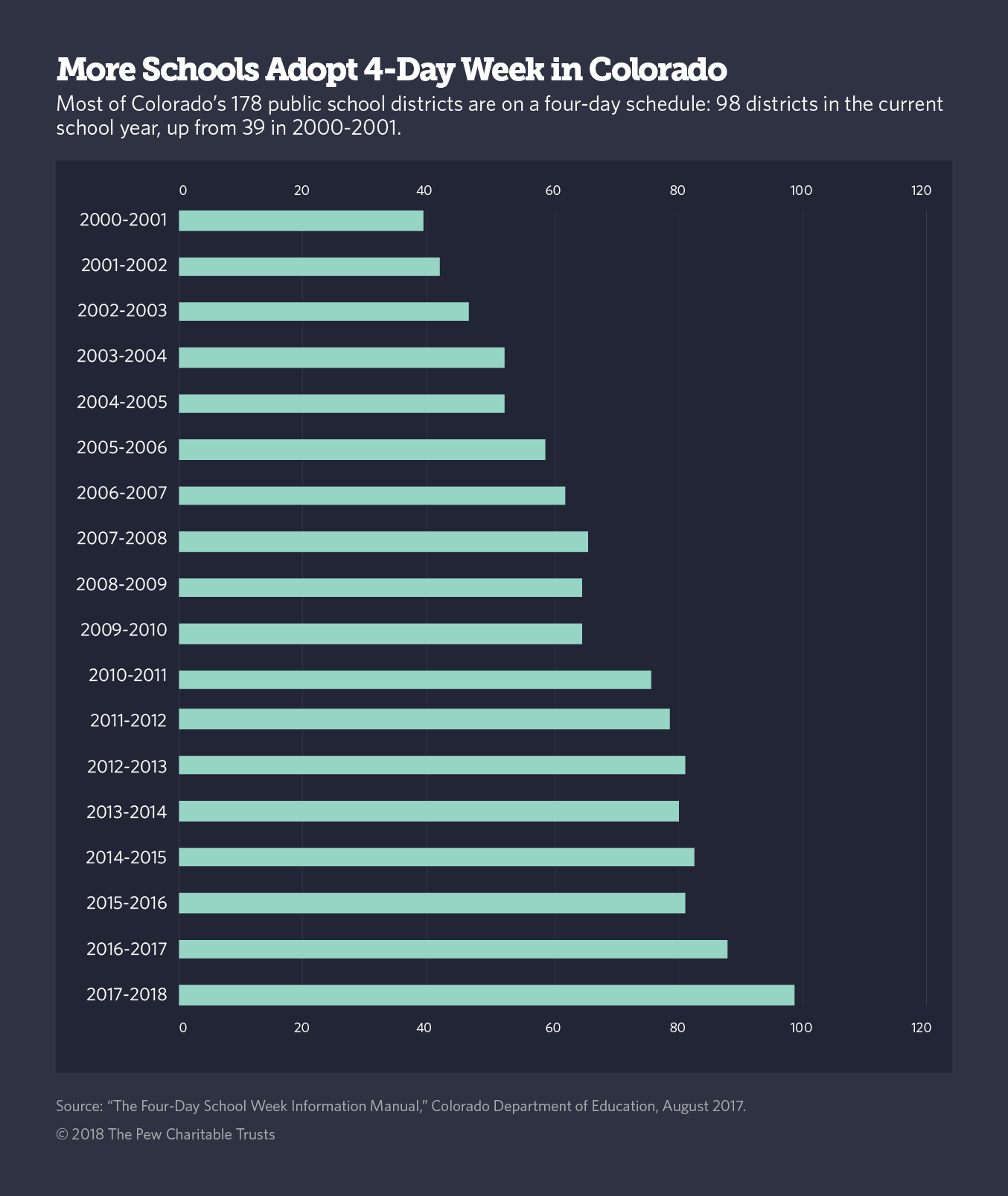

In Colorado, more than twice as many districts have state approval to hold a four-day week, compared to two decades ago. The typical district with state permission to create an alternate schedule for all its schools has fewer than 250 students, according to a Stateline analysis of state data.

To deliver the required number of instructional hours in four days, schools in the state typically add an hour and a half to each remaining day, according to Colorado’s latest information manual on four-day school weeks. Some districts only use the compressed schedule in the winter.

Chris Fiedler, the superintendent of Denver-area School District 27J, has said that he first thought of dropping a school day while crunching budget numbers. The district recently announced that it will not hold classes on Mondays next year.

The average district can save up to 5 percent of its budget by dropping a school day, according to a 2011 report from the Education Commission of the States, a Denver-based policy research organization.

But the switch doesn’t put a dent in districts’ largest line item: teacher pay and benefits. And, the report found, while four-day weeks can save money on operational expenses, such as heating and cooling, in many cases districts don’t save as much as they could because they keep schools open on the fifth day to host sporting events, tutoring programs, and teacher professional development workshops.

District 27J could save up to $1 million a year with its new schedule, said the district’s public information officer, Tracy Rudnick, in an email — that’s less than 1 percent of its budget. But the district has other reasons for making the switch. “Cost savings were never our number one goal. It is about retaining high-quality teachers and creating a clean, clear and concise schedule.”

The district is among the lowest-funded in the Denver area, with the lowest teacher salaries, said Kathey Ruybal, president of the Brighton Education Association, the local teachers union. “We get a lot of new teachers here and there, but we tend to lose them to our neighbor districts.” School leaders hope three-day weekends could convince more teachers to stay.

The new schedule will make teachers’ lives easier in other ways, Ruybal said. They’ll have more time to plan lessons over the weekend and more time to collaborate during the school day. “We’re really hoping that it’s going to improve our teaching, improve our student achievement scores,” she said.

Surveys generally show support for four-day weeks among parents and teachers, according to districts, states and education researchers who have asked adults about the schedule. In rural communities, where students travel long distances for sports games, academic competitions and doctors appointments, it can be efficient to set aside a weekday for extracurricular and family activities, according to the Colorado four-day week information manual.

Some businesses love the schedule, too. In the 1980s, one Colorado resort pushed the local school district to drop a day so teenagers would be able to work on Fridays, said Antonio Parés, a partner at the Colorado-based Donnell-Kay Foundation, which focuses on improving public education in the state.

Learning Outcomes Aren’t Clear

Dropping a school day can create new challenges for communities, however, and it’s not clear whether students benefit. Since District 27J announced its plan to drop Monday classes, parents have crowded information sessions with questions and flooded social media with comments.

“Worst idea ever,” one mother commented on 27J’s Facebook post announcing the change. She said it would be hard to get her three young children — one of whom has autism — to school at the new, earlier start time, and she’s worried the longer days will leave them exhausted. Other parents praised the new schedule.

So many parents expressed concerns about finding child care on Mondays that 27J has announced a child care program that will cost $30 for the day. Seven hundred children have pre-registered, Ruybal said.

In most Colorado communities with four-day schools, however, “the issue of baby-sitting seems to be a wash,” the state information manual says. That’s because with the longer school day, children get home closer to when their parents do. Parents may find it no more difficult to find child care for a full day than for a few hours every afternoon, the manual says.

Some studies find that the compressed schedule has no effect on test scores. Others find a positive effect. “We don’t really know how much academic outcomes are impacted,” Heyward said.

She said districts may improve their outcomes after a schedule change because teachers have to rethink instruction. Teachers have more time to plan on the weekends and more time to lead students through hands-on activities during longer weekday class blocks.

In Oklahoma, the superintendent of public instruction, Joy Hofmeister, backed legislation that would have required districts to explain to the state why they need a four-day schedule before adopting one. With advance notice, the state could better help districts plan for the change, for instance by making sure they still complied with special education requirements, she told the Tulsa World at the time. The bill didn’t pass.

And in California, 2013 legislation revokes a school’s authority to operate on a four-day schedule if test scores fail to meet targets. Washington and Minnesota have similar laws on the books, Heyward said.

A shorter schedule might have a different effect in urban districts than in rural ones. While most Pueblo teachers support the district’s decision to drop Friday classes, according to the teachers union, the Pueblo Education Association, some worry the change might harm their students from mostly low-income, Hispanic families.

Will Robinson, a teacher at a middle school on the east side of the city, said his students live in neighborhoods plagued by gang violence. His school has state permission to meet for longer school days and a longer school year in a bid to improve test scores and keep students safe. “We can work around it,” he said of the district’s plan to switch to a four-day schedule. “We just worry about where our students are going on Fridays.”

Another concern is how to make sure students are fed on Fridays, said Suzanne Ethredge, the head of the Pueblo Education Association. Almost 4 out of 5 students in the district qualify for free or subsidized school meals. Schools might continue to offer lunch services on Fridays, or community groups — such as a library that offers lunch to children during the summer — might step in to make sure students are fed, she said. The district is still working out the details.

Some districts on a four-day schedule have found creative ways to occupy students on the fifth day. Heyward said that she’s come across districts that help high school students by setting up internships, providing extra tutoring, or encouraging enrollment in community college classes.

This year the Campo School District is using a Donnell-Kay Foundation grant to pilot “Fab Fridays,” a full day of optional art, music, dance, cooking and theater activities led by teachers and members of the community, such as the local Elvis impersonator and his wife, who taught students to line dance.

Teachers who work the extra day are getting stipends to compensate them for their time, though superintendent Johnson said many of them would be happy to help without the extra money.

Fifth-day activities, like after-school activities, can offer students a rich set of learning experiences, Heyward said. The question is whether districts on a four-day schedule can afford them. “These are all districts that are struggling financially, or they wouldn’t even consider moving to this schedule,” she said.