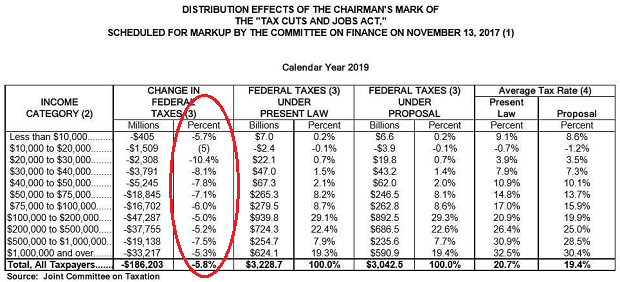

The Senate tax bill would, on average, provide a tax cut for all income groups over a 10-year period, according to the Joint Committee on Taxation’s analysis, released on Saturday. And households making between $20,000 and $100,000 a year would see the biggest percentage cuts overall, with reductions ranging from 6 percent to 10.4 percent in 2019 and 5 percent to 10.3 percent in 2027.

Those numbers could provide a powerful sales pitch for Senate Republicans, given that the JCT analysis of the House tax bill found that taxes would increase over time for taxpayers making between $20,000 and $40,000 a year and those making between $200,000 and $500,000. The headline on Politico’s story about the newest JCT analysis, for example, was “Middle class biggest winners in Senate tax plan, study says.”

Like what you see? Sign up for our free newsletter.

But analysts, especially on the political left, were swift to counter that the focus on percentages obscures the size of the proposed tax cuts, which are much larger at the upper end, while the use of average income groups conceals tax hikes for some taxpayers within each group. Some details via Politico’s Morning Tax: “if you drill down a little more, JCT also found that close to one in 10 taxpayers would see tax hike of at least $100 in 2019. Almost 15 percent of returns with between $75,000 and $100,000 in income would get a tax increase, though the biggest loser would be the group making between $200,000 and $500,000 a year.”

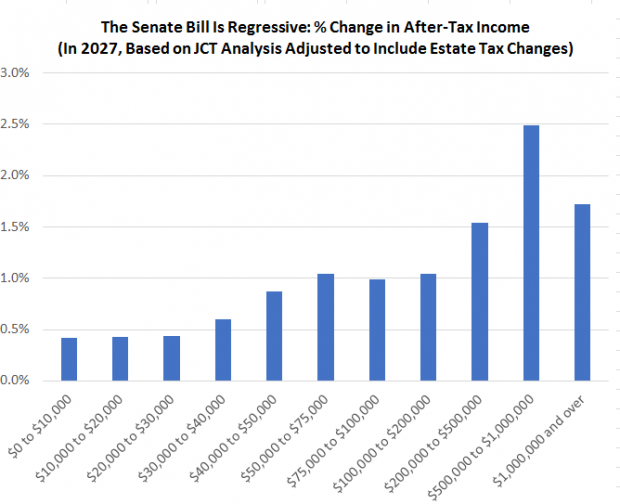

By contrast, when the Senate bill is analyzed on the basis of after-tax income rather than percentage changes, taxpayers earning between $500,000 and $1 million are most likely to benefit, as shown in the chart below from David Kamin, a tax law professor at NYU who served in the Obama administration. Kamin wrote Sunday that the Senate tax bill is “regressive, by any truly meaningful measure.” He argues that, while millionaires might not get quite as much benefit as “almost-millionaires,” they still would get a much higher boost to after-tax income than the average middle-class family.

Kamin added an additional wrinkle to the debate: Who will pay for the tax cuts in the long run? The Senate bill, like the House one, will increase deficits by about $1.5 trillion over the next 10 years, and some conservatives are already talking about the spending cuts and entitlement reform they want in the wake of a deficit-increasing tax cut. Kamin argues that the cost of the tax cut will ultimately be paid by middle- and lower-income groups as the social safety net is pared back in response to the massive drop in federal revenues.

Expect these arguments to continue as critics on both sides reach for statistical ammunition.