At a time when “fake news” and “alternative facts” are a dominant theme in American political discourse, a group of academic economists has come together in what they are describing as an effort to make sure voters and policymakers have access to verifiably true information about the state of the U.S. economy.

The EconoFact Network, as the group calls themselves, is the brainchild of economist Michael W. Klein, who holds the William L. Clayton professorship of International Economic Affairs at Tufts University. He said that the project, which officially launched last weekend, grew out of his frustration with the content of the public debate during and after the presidential election in which, he said, “so little seems to be based on real facts and serious policy analysis.”

Related: Who Will Really Pay for the Wall? GOP Struggles Over $12 Billion Price Tag

Klein, who also has some experience in Washington, having served for 18 months as chief economist in the Treasury Department’s Office of International Affairs in the Obama administration, assembled a group of more than 30 economists from universities across the country. They all agreed to provide short, factual memos on issues of national interest, written in language accessible to the layman. The memos are published on Econofact.org.

According to the group’s mission statement, “The contributing economists are encouraged to present their own conclusions or policy recommendations at the end of their memos, but only after laying out the authoritative data and facts and stating the trade-offs that different choices entail. Our network of economists might disagree with each other on policy recommendations, but all will similarly rely on widely agreed upon facts in their analysis.”

Klein said the project is, in part, an effort to push back on what he and his colleagues see as the “pernicious” problem of media reporting on economic issues that supports what they see as “false equivalence.”

“What we’re pushing against is this idea of a false equivalence,” he said. “There is a tendency often in the media to present two sides of a view even if the great preponderance of the evidence is on one side.”

Related: Trump Cracks Down on Sanctuary Cities – and It Could Cost Them Billions

He described a personal experience with the press when he was approached by a television booker to speak about international trade issues. There was broad consensus among economists with regard to the subject, but the producer informed him that the program was looking for a contrary voice. Klein demurred, but when the program aired, he was horrified to see that for a discussion about an issue that most economists considered settled, the producers had given equal weight to the positions of a lone contrarian and an economist speaking on behalf of the vast majority of the field.

In less than a week of operation, the Econofact Network has produced several of its policy memos, and paging through the site, a common theme arises: Most of the memos address claims made by President Trump or policy proposals that he and Republicans in Congress have put forward. They include the effect of a border wall with Mexico, the feasibility of the US economy growing at an annual rate of 4 percent, and whether or not China is a currency manipulator.

In many cases, the issues are ones on which Trump has repeatedly made claims that economists believe are false or dangerous. Klein insists that this doesn’t represent an effort to go after the incoming administration specifically, but is simply a product of the reality that Trump and congressional Republicans now effectively control all federal policymaking machinery.

Related: Is This How Trump Will Get Mexico to ‘Pay’ for His Wall?

“If the Democrats were coming out with a lot of policy proposals, we’d look at those as well,” he said.

And if most of the analyses seem aimed at debunking and questioning, rather than supporting policy proposals? “The fact that it seems tilted one way could just be reflecting that these policies that are coming out don’t really line up with the way economists think the world works,” Klein said. “We’re not afraid of making our voices known.”

Here’s one example, already on the site:

Will Manufacturing Jobs Come Back?

By David Deming, Harvard Kennedy School and Harvard Graduate School of Education

The Issue: President Trump has promised to bring back manufacturing jobs.

The Facts:

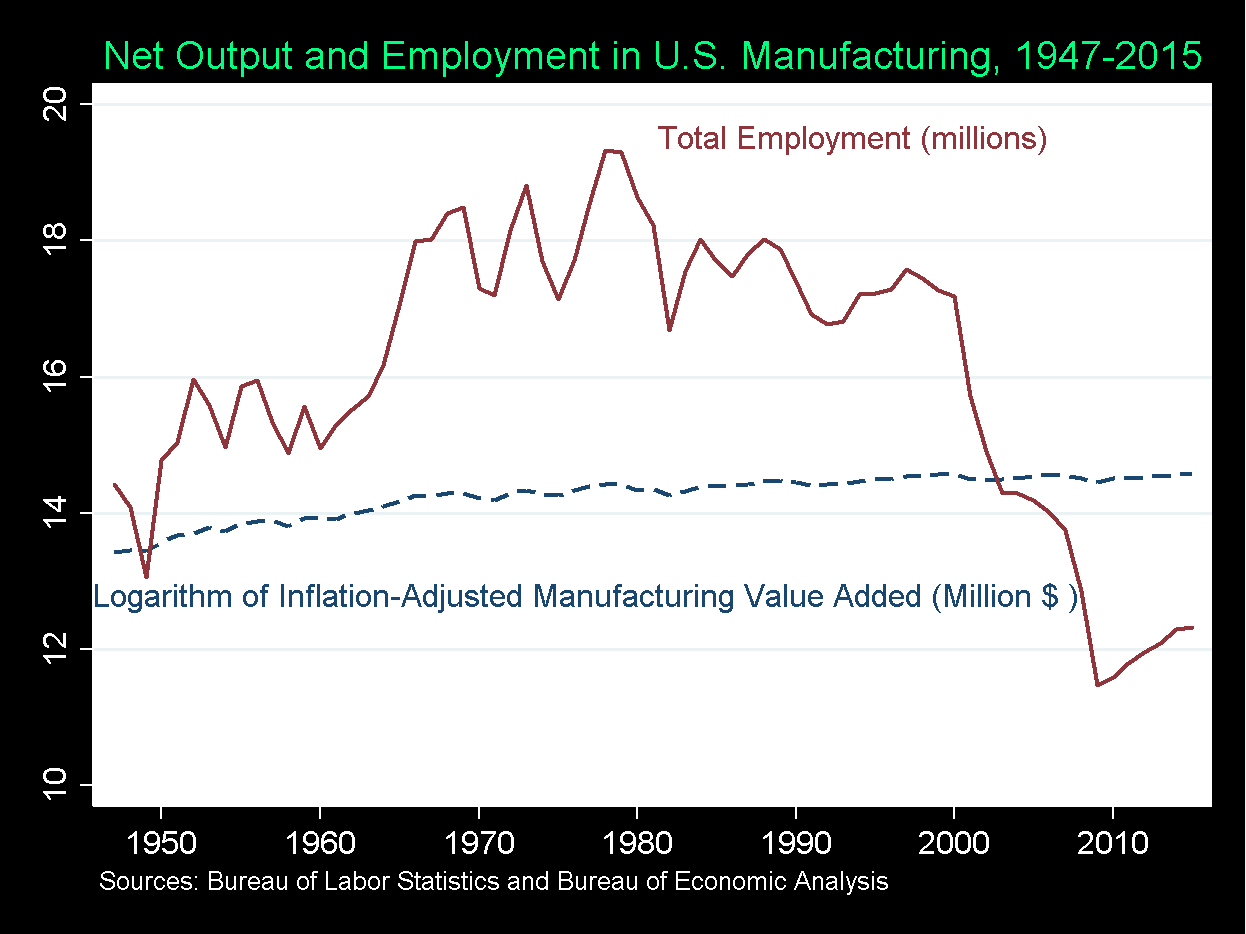

- The U.S. lost more than 5 million manufacturing jobs in the 2000s. But job losses in manufacturing began more than 30 years ago and are happening worldwide in advanced countries like Japan, Germany and the United Kingdom.

- U.S. manufacturing is booming with production at an all-time high, even as the number of manufacturing jobs has shrunk. This is because of automation. Factories in the United States and other advanced countries are making more with fewer workers.

- Automation is happening in all sectors of the economy, but much more in manufacturing than in services.

- In the short-term, infrastructure spending and public sector "make work" projects could help workers displaced by automation.

What this Means: Convincing manufacturing companies to keep — or bring back — jobs, one company at a time, is not going to restore the millions of jobs that have been lost due to technological change. In the long-run, we should be thinking of ways to change our education system towards teaching skills that are harder for robots to replace and will give people good jobs at good pay in our modern economy.