Before hospitals in the rest of the country started seeing a surge in the number of infants born with severe drug withdrawal symptoms, this town of 50,000 was already facing a crisis.

In 2010, babies born to mothers using heroin were filling up so many beds in the newborn intensive care unit at the city’s main hospital that little space was left for babies with other life-threatening conditions.

The nurses who cared for these agitated and often inconsolable infants knew there was a better and less costly way to help newborns through the painful, weekslong process of drug withdrawal.

By 2012, they had created a separate newborn therapy unit just for babies in withdrawal. Because their treatment didn’t require the same high-tech equipment needed in an intensive care unit, it was about half the cost of neonatal intensive care, according to Dr. Sean Loudin, who heads the new unit at Cabell Huntington Hospital.

The next step was to create an infant recovery center outside the hospital where newborns could be taken as soon as it was safe to leave the hospital, usually within two weeks. Not only would it free up beds for other newborns who need intensive care, it would be tailored to the needs of infants in drug withdrawal, and their parents.

The facility, known as Lily’s Place, opened its doors Oct. 1, 2014, in a one-story building that had been a podiatry practice in downtown Huntington. The city, West Virginia’s second largest, is at the epicenter of the country’s opioid epidemic, with an overdose death rate that is nearly 10 times the national average.

Staffed by the same doctor and team of nurses who treat drug exposed babies in the hospital, plus a social worker, administrative staff and additional nurses and assistants, Lily’s Place is a transitional care center where parents can visit their babies throughout the day and occasionally stay overnight before taking them home.

Infants receive the same kind of medical treatment for their withdrawal symptoms as they do in the hospital: small doses of the long-acting opioid methadone to gradually wean them from their drug dependence.

Since it opened, 135 infants have spent from two to six weeks at Lily’s Place. And the center has become a model for communities in the rest of the country that are experiencing the same kind of growth in drug exposed newborns as Huntington.

“Lily’s Place is a terrific model,” said Dr. Edward McCabe, chief medical officer at the March of Dimes. “The care for these babies is very different than the care for a small premature baby or one with a birth defect. Not to minimize what they’re going through, but these babies don’t need to be in a high-cost intensive care setting,” he said.

Rebecca Crowder, the facility’s executive director, said Lily’s Place has talked to at least 30 groups across the country that want to replicate what the center has done, including organizations from other communities in West Virginia and groups from Arizona, California, Colorado, Maryland, New Jersey, Ohio, Oregon and Virginia. Farthest along is a facility called Brigid’s Path near Dayton, Ohio, that is slated to open in April 2017.

Growing Need

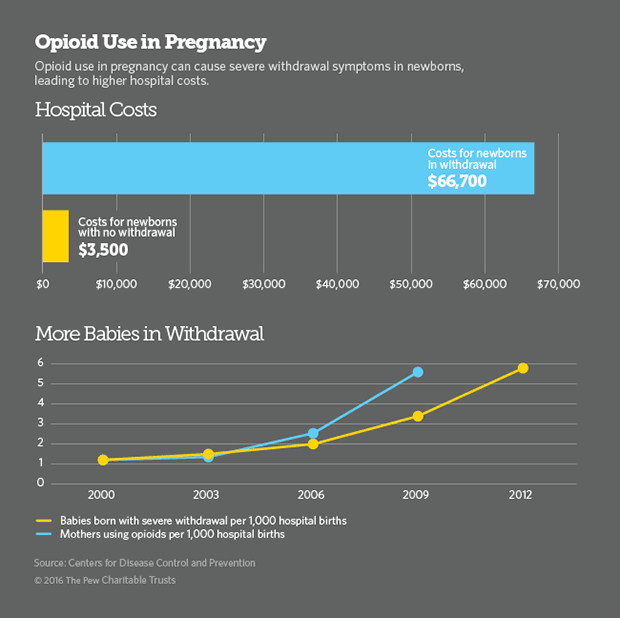

Nationwide, the number of pregnant women using heroin, prescription opioids or addiction treatment medications methadone or buprenorphine has increased more than fivefold since 2000. With increased drug use, the number of babies born with severe withdrawal symptoms has also spiraled, leaving hospitals scrambling to find better ways to care for this burgeoning population of drug addicted newborns.

Until the opioid epidemic began spreading across the country about eight years ago, most hospitals saw only one or two cases a year of what is known as neonatal abstinence syndrome. Now, a baby is born suffering from opioid withdrawal every 25 minutes in the U.S., according to the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

When a pregnant woman uses drugs or alcohol during pregnancy, some of the substances pass through the placenta to the baby. In many but not all cases, exposure to opioids, alcohol and other drugs during pregnancy can cause the fetus to develop physical drug dependence. When the umbilical cord is cut at birth, the newborn is abruptly disconnected from its supply of drugs and can suffer withdrawal symptoms, much like adults do.

Symptoms include excessive crying, sleep problems, diarrhea, vomiting, seizures and muscle cramps. The treatment is small, gradually tapered doses of either morphine or methadone over three to six weeks.

The cost of caring for a drug exposed newborn in a hospital is nearly 20 times the cost of hospital care for a healthy infant. The cost of caring for newborns at Lily’s Place is one-fifth the daily rate of a hospital intensive care unit, Loudin said.

National Models

The concept for Lily’s Place came from Kent, Washington, where a similar facility, the Pediatric Interim Care Center, was started in 1990, during the cocaine epidemic.

Its founder and executive director, Barbara Drennen, began caring for infants born to mothers who were abusing drugs by becoming a foster parent. Doctors and nurses visited her home to treat the first four babies she took in.

Later, she said, “the hospitals asked me to provide the same kind of care on a larger scale.” Today she runs a facility, funded by state grants and private donations, that cares for up to 20 newborns in drug withdrawal.

Drennen said she learned how to care for the youngest victims of drug abuse from an earlier pioneer, in New York City. Clara Hale, who died in 1992, took in abandoned and orphaned newborns, starting in 1969, and cared for them in her home.

But the founders of Lily’s Place wanted to do something different in Huntington. Instead of caring for orphaned or abandoned babies and those taken from parents by child protective services, they wanted to create a transitional therapy center that ultimately would allow parents to care for their babies at home.

By the end of this month, Crowder said the Lily’s Place website would offer a guidebook to help ease the time-consuming process of explaining to others how they created the facility. It will, for example, explain how to create a nonprofit and raise funds, and how to comply with building codes and meet staffing requirements to be licensed as a medical facility, she said.

A Soothing Place

Anyone who has walked through the doors of Lily’s Place knows it is unlike any medical facility they’ve ever visited. There is no hustle bustle and no whirring and beeping technology. The lights are dimmed and the staff speaks in hushed tones. Parents wait in silence to visit their babies.

Each baby or set of twins is cared for in one of 15 private nurseries with a crib, changing table and rocking chair. The rooms, all cheerfully decorated, allow parents to visit and hold or rock their babies in private, without disturbing the other infants.

While the babies are cared for at Lily’s Place, a staff social worker helps parents and their extended families prepare their home to become a safe and nurturing place to care for their new babies, who typically continue to suffer from mild withdrawal symptoms for several months.

Infants in drug withdrawal can be fussy and more difficult to care for than other infants, staff social worker Angela Davis explained, so each family member is trained on how to care for their infant. Davis also helps parents find jobs, better housing, financial help and addiction treatment.

Once their symptoms subside and they no longer need to be dosed with methadone, the infants are ready to go home with their parents.

A staff social worker visits the home a week later, to make sure the parents are coping well with their new baby. Visits are then cut to once a month, then once every three months, or as needed.

Parents are free to call nurses at Lily’s Place, who are on duty 24/7, or stop in for a visit. In addition, a pediatric neurologist holds clinics for parents twice a month.

With a bare-bones budget of $1 million, Crowder said Lily’s Place relies on volunteer work and local donations, which continue to pour in. The building was donated by a Huntington family, and local residents have paid for most of the supplies, including diapers, furniture and clothes, she said.

Regulatory Hurdles

When they were in the planning phase, the founders of Lily’s Place sought the advice of U.S. Rep. Evan Jenkins, a Republican, who at the time represented Huntington in the state Legislature.

Jenkins helped them get temporary approval to operate as a medical facility, under a state pilot program that initially classified them as a long-term care center for the elderly and the disabled. Later, he backed a state law that created a new licensing designation for Lily’s Place and others like it.

Now he’s negotiating with the U.S. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services to get the needed approval for Lily’s Place to receive reimbursement through Medicaid, the federal-state health insurance plan for the poor.

Jenkins was elected to the U.S. Congress in 2014. He supported a recently enacted federal law, the Comprehensive Recovery and Addiction Treatment Act, that includes a provision calling on the federal government to smooth the regulatory path for other communities that wish to open facilities like Lily’s Place.

It’s in the government’s interest, he said, to allow other communities to develop similar facilities. It would free up hospital intensive care units and save taxpayers a lot of money.

This article originally appeared in Stateline, a nonpartisan, nonprofit news service of the Pew Center on the States that provides daily reporting and analysis on trends in state policy.