While politicians in both parties continue to voice concern about the economic plight of the middle class, a more urgent crisis may be the growth in the number of American families trapped in “deep” or “extreme” poverty.

The problems of the poorest of poor in the U.S. received scant discussion during the recent round of budget talks that produced a fiscal 2016 Republican blueprint for gradually eliminating the deficit. The plan would require more than $5 trillion in cuts to domestic spending over the coming decade – many in social safety-net programs for low-income Americans.

Related: The Surprising Fact of Hunger in America

President Obama and Democratic lawmakers are demanding far more money for key domestic programs, including some vital to the country’s poorest families, before they sign off on specific spending bills for the coming year.

According to recent research, the number of households living on $2 or less in cash income per person per day in a given month increased from about 636,000 in 1996 to about 1.65 million in mid-2011, a growth of nearly 160 percent.

What’s more, over six percent of the population – including 7.1 million children – live in “deep poverty,” which experts define as having a household cash income of less than half the federal poverty threshold.

To give that some added context, the threshold for being in deep poverty today is having an annual cash income of less than $5,886 for an individual, $7,965 for a single parent with one child or $12,125 for a married couple with two children. By comparison, the median household income last year was $53,891.

Related: Puzzling Rise in Food Stamp Use as Economy Improves

This troubling growth in the number of the poorest of poor Americans is likely a byproduct of the past historic recession and the long-term residual effects of the 1996 welfare reforms approved by Congress and former President Bill Clinton, according to a new analysis by the Brookings Institution..

“Strengthened work requirements and newly implemented time limits meant that many low-income families entered work, received higher tax credits and improved their situation,” wrote Richard V. Reeves, a senior fellow in economic studies at Brookings and research assistants Emily Cuddy and Joanna Venator. “But those unable or unwilling to move from welfare to work as intended received less cash assistance from the government and became reliant on a hodgepodge of government support, such as [food stamps], housing subsidies, Medicaid/CHIP.”

For the small portion of those in deep poverty who managed to find and hold jobs, the federal government provides them with some important assistance, including the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC), Child Tax Credit (CTC), and Additional Child Tax Credit (ACTC). For example, a married couple with two children and earning $10,000 a year are eligible for a $5,060 cash refund through the EITC and ACTC. That boosts their disposable income by just over 50 percent.

Related: Social Safety Net Lifts 48 Million Out of Poverty

But the majority of those without any appreciable earnings must rely entirely on family and government support, as Reeves and his colleagues note. Typically, those in deep poverty are eligible for family-friendly tax credits and direct assistance in purchasing food, shelter and health care—all programs without the strict work requirements of the 1996 Temporary Assistance for Needy Families welfare reform law.

So who are among the deeply poor? According to the Brookings study:

- They are typically U.S.-born, white and living in a family.

- Many of them are children. Over 10 percent of children younger than 6 live in families in deep poverty.

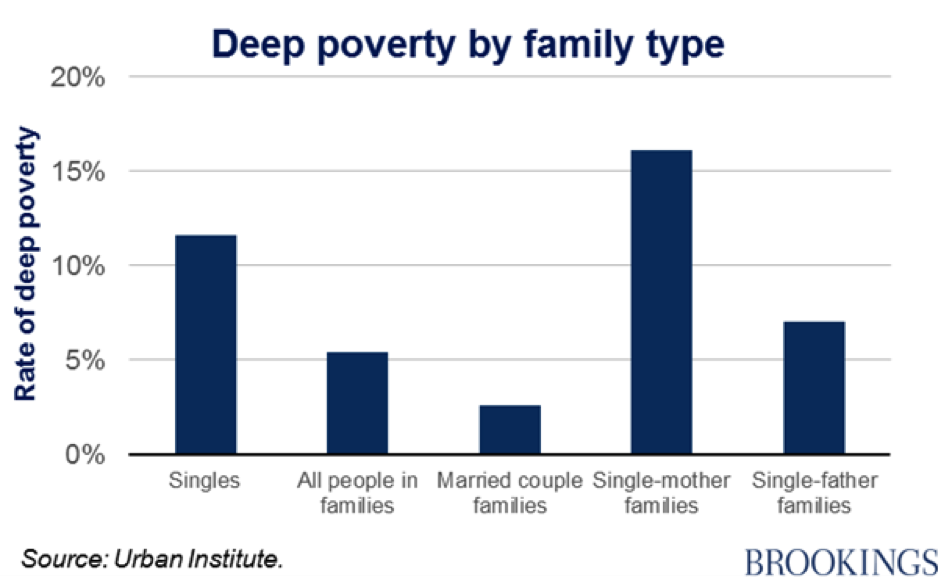

- Single-mother families and individuals are at greatest risk of falling into deep poverty.

Related: Poverty Moves Into the Burbs

- Many of them are minorities. Ten percent of black Americans and 12 percent of Hispanics are in deep poverty as compared to only 5 percent of whites.

Top Reads from The Fiscal Times